There are literally hundreds of approaches to therapy. They can be viewed critically as does Vybíral, Z. (2014) in:

Thomas’s Psychotherapy Encyclopaedia of Critical Psychology, Chapter 253.

….. where he identifies approximately 250 different therapies recognized by the scientific community; and that will be conservative estimate nearly ten years later. Vybíral concluded that therapy was especially effective for people who are ready to change; that is, for about 75 % of clients.

He said that some 5-10% of clients showed a deterioration of their mental state during therapy. Vybíral, and several others, notice the implication of this: there is little variation in outcomes between followers of different models of counselling.

You can research this area if it helps. Look up ‘commonalities between therapeutic models‘ in a search engine!

Beware panaceas!

New approaches are being developed every year. One I came across (December 2021) is ‘Religiotherapy’, in a paper sub-titled “A Panacea for Incorporating Religion and Spirituality in Counselling Relationships“. ‘Panacea’, says it all, does it not? Everyone keeps finding one!

Here is another perspective – the gur?-chel? relationship – based on the work of an Indian psychiatrist, Jaswant Singh Neki. I read about it in a Paper written by Vincenzo Di Nicola and entitled The Gur?-Chel? Relationship Revisited: A Review of the Work of Indian Psychiatrist Jaswant Singh Neki.

This approach attracted me as it comes from a very different cultural perspective. It so different from my own brief, small experimental perspective as it “encourages permanent dependency” in the working relationship. The guru assumes total responsibility for leading the chela (client or novitiate) toward self-mastery “through the disciplines of persistence and silence”. Neki, 1974.

He suggests this approach would be “most suited to cultures valuing self-discipline rather than self-expression, and creative harmony between individual and society”. For me, there is not much evidence of ‘harmony’ in our present world when I observe the impact of structural inequalities. Compare Neki’s approach with the ‘argumentative’ perspective of Dialectic Behaviour Therapy (DBT) with its focus on compare this, with that.

Yet it still seems true that good therapists, from a range of cultures and practising in different types of therapies, achieve approximately the same results.

The Dodo Bird paradox

In the business, this finding is called the paradox of “content non-equivalence and outcome equivalence“, a fancy way to say: you get roughly the same results whatever approach you take! It was this finding that led Rosenzweig (1936) to borrow from Lewis Carroll the motto used by the Dodo Bird in Alice in Wonderland: everybody has won, so all shall have prizes.

The main conclusion from all this is that common factors appear to be responsible for the benefits coming out of therapy – rather than ingredients specific to particular theories. As a consequence, experienced therapists tend to offer a mixture of things. If you choose carefully, or if your are lucky, they will negotiate that ‘mixture’ with you.

Barry Duncan and Scott Miller put it like this:

The love affair with models blinds therapists to the roles clients play in bringing about change (Duncan, Sparks, & Miller, 2000). As models proliferate, so do their specialized languages, systems of categories, and arsenal of techniques. All such articulations take place outside the awareness of those most affected. When models, whether integrative or not, crowd the thinking of therapists, there is little room left for clients’ models.

Barry Duncan (2000) The Client’s Theory of Change. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration Page 169ff

The hidden influencer (not all are on social media!)

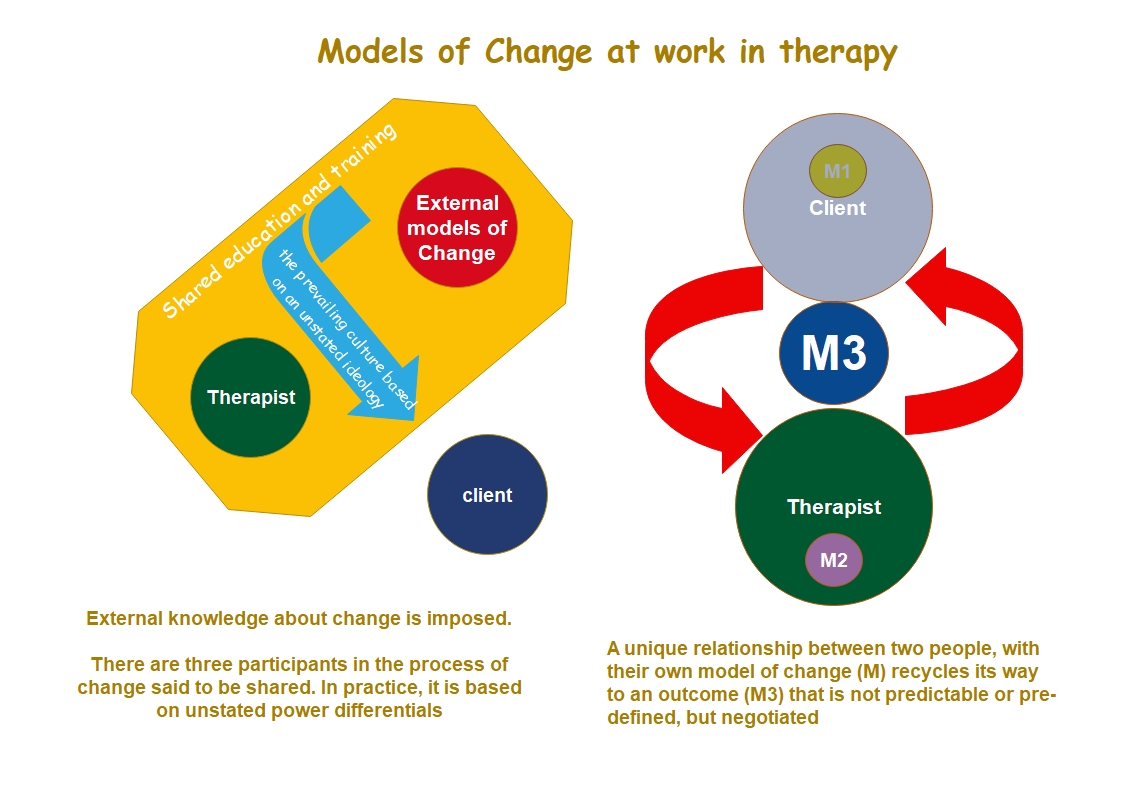

My header illustration offers the warning that ‘negotiation’ is not assured when inequalities exposed here are taken for granted.

There is a serious side to hi-jacking the Dodo Bird’s point of view. If you scratch it enough, a political point emerges: namely, that therapy became dominated by the medical profession and, by association, the principles and methods of science. It’s worth taking a closer look at the impact of this evolutionary process.

I can imagine you saying: but you are taught to be person-centred: accepting and sensitive to my views and feelings?

True-ish, but the key word is ‘taught’. Too often training is accompanied by an unstated do as I say, not as I do. This is not entirely the fault of trainers and educators. The didactic manner of teaching – let me tell you a thing or two – may have faded, but it is not gone and forgotten.

It is a struggle to put it ‘instruction’ behind us. It has become sophisticated in the modern world where features of the culture are made more explicit. Even then, one set of instruction is easily replaced with various ‘isms’ (this is not a politically correct thing to say).

Princess Di knew about it ….

Let’s look at this subtle problem using my header illustration. Princess Di got there before me. On one infamous occasion, she said “there were three of us in the marriage” and the same is true when any of us work in therapy. It is not always wise to spell out this fact; when Di did it she was breaking a ‘rule’ and she paid a price for it. I am doing the same thing with my diagram.

You need to know how I came to know what I know ….

…. only then can you find a strategy for watching out for the hidden influencers I have absorbed.

…… and only then can you find out what you need to understand about my Achilles Heel, and really negotiate that M3 on the righthand side of my diagram.

On the one hand, and on the other

The left-hand side of the diagram makes explicit the power differential that exists between the ‘shapers’ of our culture, community leaders, politicians, educators, practising therapists and even some ‘clients’ in positions of power.

The right-hand side of the illustration describes an alternative way to obtain a negotiated result in therapy. In this alternative view of therapy everyone can, indeed, get prizes but only if the ability to negotiate is robust and explicit.

Of course, if you are lucky, you may find a ‘scenic route’ that works for you using your own efforts. At the same time, there is a trap: you cannot know what you do not know. On your own – you may overlook or discount something important.

For that reason, my philosophy has been criticised for leaving too much to the client. It can help to have some-one working alongside you, as I say a few times – but not all the time. If you choose to involve another, please keep in mind that both you and any therapist will be ignorant about what works for you – as a team – in the first instance.

I include myself in this! That’s one reason why I ask you to ‘just notice’ things as a first small and safe experiment!

DO NOT BE PERTURBED BY THIS CONCLUSION

It can provide viable evidence that everyone involved has to respond to small defeats arising from not-knowing. For more on this, see my pages on relapse work and faltering during therapy.

‘Evidence’ is touted as a key requirement for effective therapy. There is even an approach called Evidence Based Treatment (EBT). The evidence is that EBT does not necessarily improve treatment effectiveness or outcomes! Even more odd is that the model is called Perceptual Control Theory (PCT).

New skills or old skills? What’s needed to make change?

I say ‘odd’ as Richard S. Marken and Timothy A. Carey (2014) published a Paper in Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy called Understanding the Change Process Involved in Solving Psychological Problems: A Model-based Approach to Understanding How Psychotherapy Works. In it they say their ‘new’ model divides problems into two categories: those that can be solved using existing skills and those that require the generation of new skills. They assert that psychological problems belong in the second category. I suspect Lane Pederson is taking a similar view in relation to Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT).

I’ve little concern about the view that change can be learned through practising new skills yet old ones have their uses. What is more troubling are hidden values. Marken and Carey continue by saying “therapy will be efficient when the reorganization process is focused at the right level of the client …. when the client’s reorganization system – not the therapist – has managed to come up with a solution“. [Note my emphasis] I love the sentiment behind this statement, but the use of ‘right’ and labels such as ‘reorganization system’ undermines their assertion.

These words offer an insight into the subtle impact of ‘unstated ideology’ – that is; rules that power-brokers and influencers (including me), project on to the backcloth of our worlds.

How do I speak out about the unspoken?

I am concerned that you will find yourself swimming against the tide as you seek to take in the impact of these unspoken rules. Marken and Carey do not consider one further step; ‘solutions’ come out of a negotiation that acknowledges the uniqueness of the two minds seeking to make something unique during the therapeutic event.

Instead, yet another therapy finds its way into the world. Most cultures have systems for ensuring power-brokers hold the reins and control events without this being obvious to the casual observer. The names of therapies tell you a lot about the individual author(s) who seek to be in charge – at the very time you are being told: ‘ gosh, no, I do not want to be in control of your life: how can you think that‘!

Sadly, the clue for this oddity is in the title: Perceptual Control Theory (PCT). ‘Control’ issues appear to be at the primary motivator for the proliferation of labels. Compassion focused therapy (CFT) deals with it rather well – linking control features to our motivation to change.

You may be able to develop a new hobby: spot Robin being controlling! It’s difficult not to let my guard slip from time-to-time. Sometimes I spell it but even that can be patronising, eh?

Finding ways to work ACROSS models of change

In short, what a client or therapist first say about the nature of any ‘problem’ may be of less importance than we might think. So says Nathan Beel, an Australian researcher. He invites us, along with many other writers, to learn what works across therapies. So how can you and I find out what works for us? It is a precarious business as you will need to find out what works for you!

Even well-respected researchers such as Norcross (1997) suggests that this challenging approach to the integration of available models invites confusion and irrelevancy. He required that the ‘‘me and not me’’ elements be established – note the ‘and’, rather than a ‘with’. He seems to exclude the ‘we’ or, at least, he is troubled by the even more complex boundary presented by ‘us’. You – working with me – are just one of the ‘commonalities’. I’d assert that it is a rather important one too often missed. Dan Siegel seems more able to spot it with his new word: MWe.

With that said, this website exists to address some of the better-known therapies. What are the features some display?

Consider, for example, this summary of some models:

The Medical Model: characterised by

1. Diagnostic categories, syndromes, diseases

2. Focus on Individual, rather than systems perspective

3. A narrow view of physical causation: external substances or forces, or genes

4. Use of physical modalities of treatment: pharmacology, surgery

5. A separation of mind from body

The Biopsychosocial Model: characterised by

1. Seeing disease as the endpoint of a process and accepting that disease and illness are not seen the same way by doctor and patient.

2. Seeing the individual as part of a system, and illness in the individual as the expression of a systemic problem

3. Mind/body are not separated, but seen as interactive.

4. Sees illness as having meaning beyond its direct effects on the person: Why this person, why this illness and why now?

Gabor Mate goes on to summarise what he terms:

A Super-system

- that is: psychoneuroimmunoendocrinology! This comprises:

1, The psyche: the brain centres that perceive, interpret emotional stimuli and process emotional responses.

2, The nervous system that is:

–“electrically” wired together, with its two branches: voluntary and autonomic.

–the autonomic system helps modulate blood flow, muscle tension

–the hypothalamus as the apex of the autonomic system (and also of the hormonal apparatus)

— I’d would add that Stephen Porges’ material on the working of the Vagus system can be incorporated in here.

3, The endocrine glands

–endocrine: an organ that secrets a substance into circulation to affect

another organ: e.g., thyroid, adrenal, pituitary

— the hypothalamus as the master gland

4, The immune system

–“the floating brain”: functions of learning, memory, response

–bone marrow, thymus gland, lymph glands, white blood cells, spleen

5, Neurotransmitters/chemical messengers in the nervous system: such as GABA (do you want to know this? GABA is a non-protein amino acid that functions as an inhibitory neurotransmitter throughout the central nervous system) and glutamate (a principal excitatory neurotransmitter in brain).

Doesn’t stop there, I fear, as what is now needed on top of all this is Dan Siegel’s notion of Mind that considers what happens when a group of people mix their ‘super-systems’ (do not even try to do the Maths!).

Super systems are not so new as some think

Work on ‘super-systems’ goes back further than some of us think, a couple of centuries one could suggest. Ken Wilber, a 20th century American philosopher, described a philosophical map bringing together more than 100 ancient and contemporary theories in philosophy, psychology, contemplative traditions, and sociology.

He worked to avoid seeing his perspective as “the one correct view”. but still ended up with the Integral Theory! This material described a framework for understanding and valuing the different philosophical traditions, their relationship one with the other.

What I like about Wilbur’s world-view is the recognition of an ‘evolution’ of ideas that respected previous perspectives, and the writers who have contributed to them. Although his theory is most closely-linked with the ?humanistic and transpersonal forces?, Wilber himself (1983) described his work as integrative as he believed conventional psychology was ‘at home’ in his approach.

He saw Integral psychology as including – possibly transcending – the four forces in psychology of psychoanalytic, behaviouristic, humanistic and transpersonal. Now, of course, we have an ability to link all this with the growing convergences of psychology with the neuro-sciences.

It takes a lot of skill to just notice all these world views, but it enables me to accept that the human mind is not making 100 percent errors, as James Duffy put it in his Primer on Integral Theory and Its Application to Mental Health Care (2020).

I can avoid judgments of ‘right and wrong’ and, instead, approach each perspective as a partial truth. With that, maybe, I can figure out how these partial truths fit together to better understand my world. If I can integrate them and, if I can make good relationships, might I help others to do the same?

This latter point is important; when Steve de Shazer and others researched Milton Erikson’s pragmatic (or atheoretical) approach to therapy, they found a number of visible patterns in his approach to ‘clients’; five, patterns as I understand.

Unfortunately, a sixth pile of recorded cases they studied remained the largest and they were ?unclassifiable?. Erikson’s approach refused to be fitted into any theory. He would have been pleased by that – but less taken with the modern catch-all name – Eriksonian Therapy!

As I see it, that largest, sixth pile could not offer a ‘patterns’ as each file reflected a rather more complex pattern emerging from client-with-Erikson. Without material from that mixutre, the sixth pile must remain ‘unclassified’. Interestingly, figures around the 80% mark keep recurring when research assesses what is ‘successful’ therapy!

I wonder why that is??

Processes of change

One way of trying to explore this minefield is to side-step the physics and chemistry and to explore the processes of change. In 1977, James Prochaska embarked on a journey through the various systems of therapy. He concluded that theories of psychotherapy can be summarized by ten processes of change. It’s a lot to cram in and I am reducing this to seven. Apologies to any-one offended by my summary!

Some folk may well not wish to be associated with some of my labelling but I am not writing an accurate research review. I am creating a device to help you devise safe experiments.

When you sense I am misdirecting your thoughts, be alert and look to your left and right. The seven categories I offer are:

Consciousness raising

That is, when you bring the unconscious, in to the conscious.

This is found in the ‘traditional’ approaches of psycho-analysis, Freud and Jung and many others. Also, the psycho-social model of Erik Erikson and Jean Piaget, and others, once dominated therapy by covering a range of ideas about how humans grown and develop. It is difficult to offer an helpful link into this vast area of research and study. However, you may find the page on ‘history’ of some help.

Also, the Discount Matrix and the Johari Window both assume there are things that are not known – yet worth knowing!

Self-liberation

…. breaking out of your prison created by your past. This can be seen in the radical therapies from the Lesbian, Gay and Bi-sexual and Transgender movement (LGBT), or in the material of Dorothy Rowe, and many others. I believe the Person-Centred School, emerging from the work of Carl Rogers, would want to see itself operating in this area even if the day-to-day therapeutic experience may not meet the expectations! Here, in the UK, there was a whole movement, seemingly short-lived, started by a Scottish psychiatrist, R.D Laing. Thomas Szasz did a similar job in the US.

Social liberation

…. working with others to change the existing social order. Rather a favourite of radical and revolutionary thinking, this approach is well represented by Extinction Rebellion and the older tradition of the radical South American RC priest, Paulo Friere.

More can be found on: https://justliving808.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/freire-ch-1-and-2.pdf

Counter-conditioning

….. involves ‘inoculating’ yourself against past habits by the deliberate alteration of behaviour, attitudes and beliefs. Cognitive models such as Eye Movement De-sensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) are helpful here. Transactional Analysis is a particularly good example as it helps us to identify our life Script and amend it. It has informed my own personal development and , consequently, a lot of what I have written in this website.

Stimulus control

Some models use affect regulation to help you to discriminate what you can control from experiences and events beyond your own control. One example, and there are many, include; https://www.emotionregulationtherapy.com/.

Contingency management

…. summarised as changing behaviour to hope for the best, and prepare for the worst, an approach well represented by Albert Ellis’s Rational Emotive Therapy (RET), and its cousins . See https://www.verywellmind.com/rational-emotive-behavior-therapy-2796000

Dramatic relief

…… that can be represented by Psychodrama and the work of Jacob Moreno and his followers. I would include more modern form of dramatic relief such as body psychotherapies and Walking Therapies. All may include talk, but they place value on movement as well. I suspect that the late Archbishop Tutu was an exponent of this approach!

For further information on a traditional school, see: https://www.crchealth.com/types-of-therapy/what-is-psychodrama/. Also the work of recently-deceased Arthur Janov and his ‘Primal Scream’ fits in here. For more information, see: www.primaltherapy.com/what-is-primal-therapy.php.

The term ‘trans-theoretical’ is often used to cover a number of models that want to integrate different approaches – seeking to be above any one theory.

Get above the individual claims

In some ways, this has been one of my intentions writing up this website. I share the approach that recommends that ‘good’ therapy involves us in acting differently, as well as thinking differently.

Too often, however, you may find the action is prescribed by the model, not by your own decisions.

I am asking you to move from the recommendations of others, toward confident design of your own safe experiments. In case I over-state my case, I should say that action might not be everything.

This tendency to proscribe, or instruct others is often overlooked, or carefully concealed; the ACT Approach does explicitly ask you to find your own direction, but too often, in other models, prescriptions are concealed. Why? Too often, to enhance the reputation of the ‘founders’.

One safe experiment

If you are intrigued by this idea, research any model of therapy you can find and seek out the implicit instructions. Often, they are to be found in the ‘values’ that researchers identify. Look out for the ‘shoulds’, the ‘musts’ and the ‘best or worse’.

As far as I am concerned, if it helps to state it explicitly, my education, training and experience has drawn me toward one way:

Transactional Analysis (TA): based on the mid-20th Century work of Eric Berne.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): based on the work of so many people, although the names of Beck and Albert Ellis come immediately to mind.

Eriksonian Therapy: based on the clinical hypnosis and the work of Milton Erikson (not Erik Erikson, a Scandinavian psychologist).

Systems thinking: of Virginia Satir and Paul Watzlawick.

Each perspective influences the work I do now but I am aware there are other approaches that have helped me to understand how therapy can work for different people. For instance:

Emotional Freedom Therapy (EFT):

Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR):

Mindfulness: of Kabat Zinn and others

Body psychotherapies: of Pat Ogden and Peter Levine

Neuroscience: as summarised by Stephen Porges.

For those interested in trauma therapies, it is increasingly impossible to overlook:

Parts Therapy: such as Transactional Analysis (TA) and John Omaha’s perspective.

Psychodrama (see item 7, above):

Neural Feedback

….. as well as Action programmes such as Yoga, Pilates and Eastern Meditations such as Qigong and Tai Chi.

Many therapists embrace an integrative perspective in their practice – taking views from a number of schools and putting it together in their own practice.

There are a number of arguments about the nature of this ‘integrative’ practice, but the primary focus, as I understand it, is to affirms the inherent value of each individual.

Put it all together, and what do you get?

The integrative approach absorbs an affective, behavioural, cognitive, and physiological level of functioning, as well the spiritual dimension of life. It is not always obvious where the boundary is between the practitioner doing this and client. Some models of change are troubled by fluid boundaries and others embrace them.

BUT who is doing the integration?

Can the ‘relationship’ do it, as well as the individuals engaged in therapy?

When we look closely, the focus is often, in practice, on the practitioner’s perspectives and actions. ‘Noises’ are made about the unique relationship of ‘therapist-and-client’ — most obviously by the Person-Centred movement where there is less clarity offered about how this joint enterprise works day-by-day.

With the stated aim “to facilitate wholeness“, I would suggest that the older Gestalt perspective has much the same to offer. Indeed, would not most models of change value a process that enhances the “quality of the person’s being and functioning in the intrapsychic, interpersonal and socio-political space“. Quotes taken from: https://www.integrativetherapy.com/en/integrative-psychotherapy.php.

Not too sure how you do that in the real world! Folk have tried. Researchers called Norcross and Goldfried (2005) wrote up an inaugural edition of The Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration an early compilation of the early integrative approaches to therapy.

It appears that six motivational categories can be discerned in an integrative therapist’s practice.

- Empiricism: what you see is what you get? Hmm.

- Scientific Attitude: a willingness to make an ordered study of the work they do. The modern world, here, has to struggle with the method of scientific enquiry, as well as the nature of relevant evidence.

- Therapeutic Humility: here the client gets a look-in as it assumes a therapist has enough humility to include a ‘client’ perspective. Shame the ‘client’ is still a ‘client’ and humility is too often confined to the provisional language most often used by practitioners!

- Perceived Inefficacy: Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura) described the construct of perceived self-efficacy as the belief that one can perform novel or difficult tasks and still attain desired outcomes. ‘Inefficacy’ suggest that it is difficult to match tasks and outcomes. I take a different view and believe that you can work with your therapist, or on your own, to make sense and to live with contradictions. Complexities do arise from the absence of order, predictability and a lack of meaning in my life. I suggest that seeking a pattern in my life is a ‘draw’ that I can understand, but is less necessary than one might think!

- Need to Comprehend: there is a ‘nod’ her to both client and practitioner needing to comprehend and experience therapy as helpful.

- Striving for Congruence. That is, a match between the way in which therapy is delivered, and the plans of action negotiated during therapy.

A useful list, in some ways, as a demonstrates both the knowledge base absorbed by therapists, as the develop their own personal therapeutic approaches, together with an acknowledgement of their own personal needs and desires. All that may be needed, now, is to integrate the client contribution to the therapeutic situation.

What might you discern in any clinical relationship you are developing at this time, with a practitioner?

As and when I am able to offer some connection to these very different approaches, you will see hyperlinks appear in the above list.

Despite all this information questioning where models come from, researchers and educators continue to look for more more models. Consider this statement:

The urgent challenge for clinicians and researchers is constructing a conceptual [my emphasis] framework to integrate the dialectical work that fosters collaboration, with a model of how clients make progress in therapy …. we propose a conceptual account of how collaboration in therapy becomes therapeutic. In addition, we report on the construction of a coding system [for the] therapeutic collaboration coding system.

Miguel M. Gonçalves Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice (2013), 86, 294–314

We are still teaching therapists and clients how to make progress!

Further links to consider

Selecting a therapist (is not about the ‘model’ they follow)