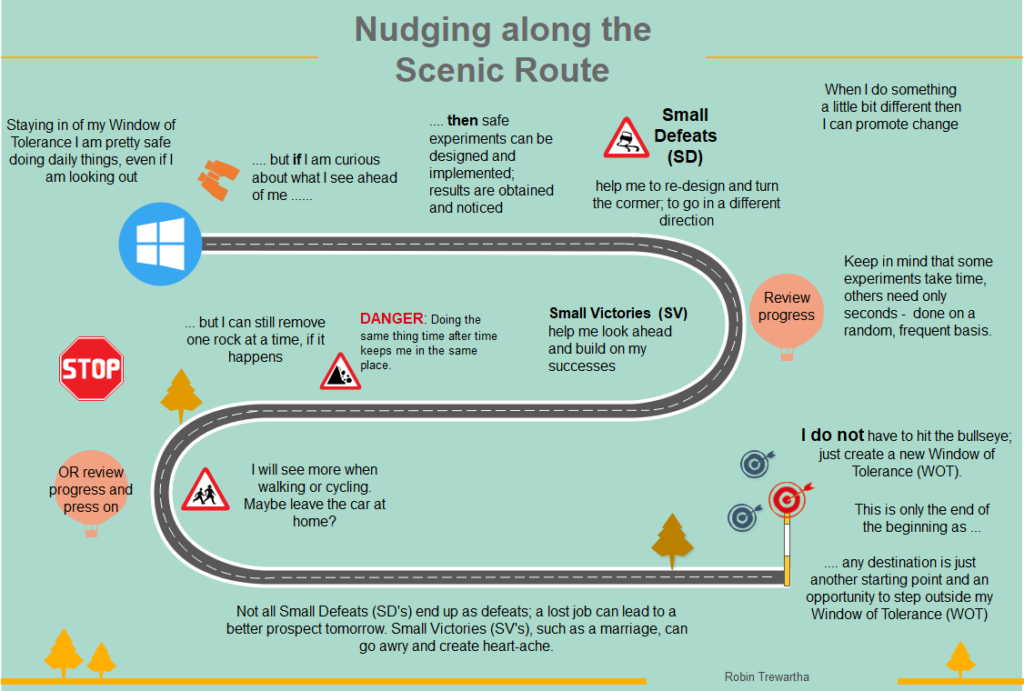

The Learning Curve, included above, offers some information to help with the small, safe experiments designed to create your own scenic route.

Each reader will review their progress through this web site differently. Some will pop in just briefly, others return to one or two pages a few times and others might work through the whole thing systematically.

You might conclude that the long list of experiments has become irksome: ‘there is too much to learn‘, or ‘I can’t make sense of all this‘. Other times, you may have an enthusiasm for one idea or a whole range of ideas.

Such reactions are understandable although some will help foster change better than others. Whatever way you choose to use this web site will say something about your own style of learning. Your style will impact on the way in which you design and implement a safe experiments.

Management of them will now be part of yet another experiment. Your understandable reaction is telling you something important. That said, there are some common features of learning that might be useful to highlight.

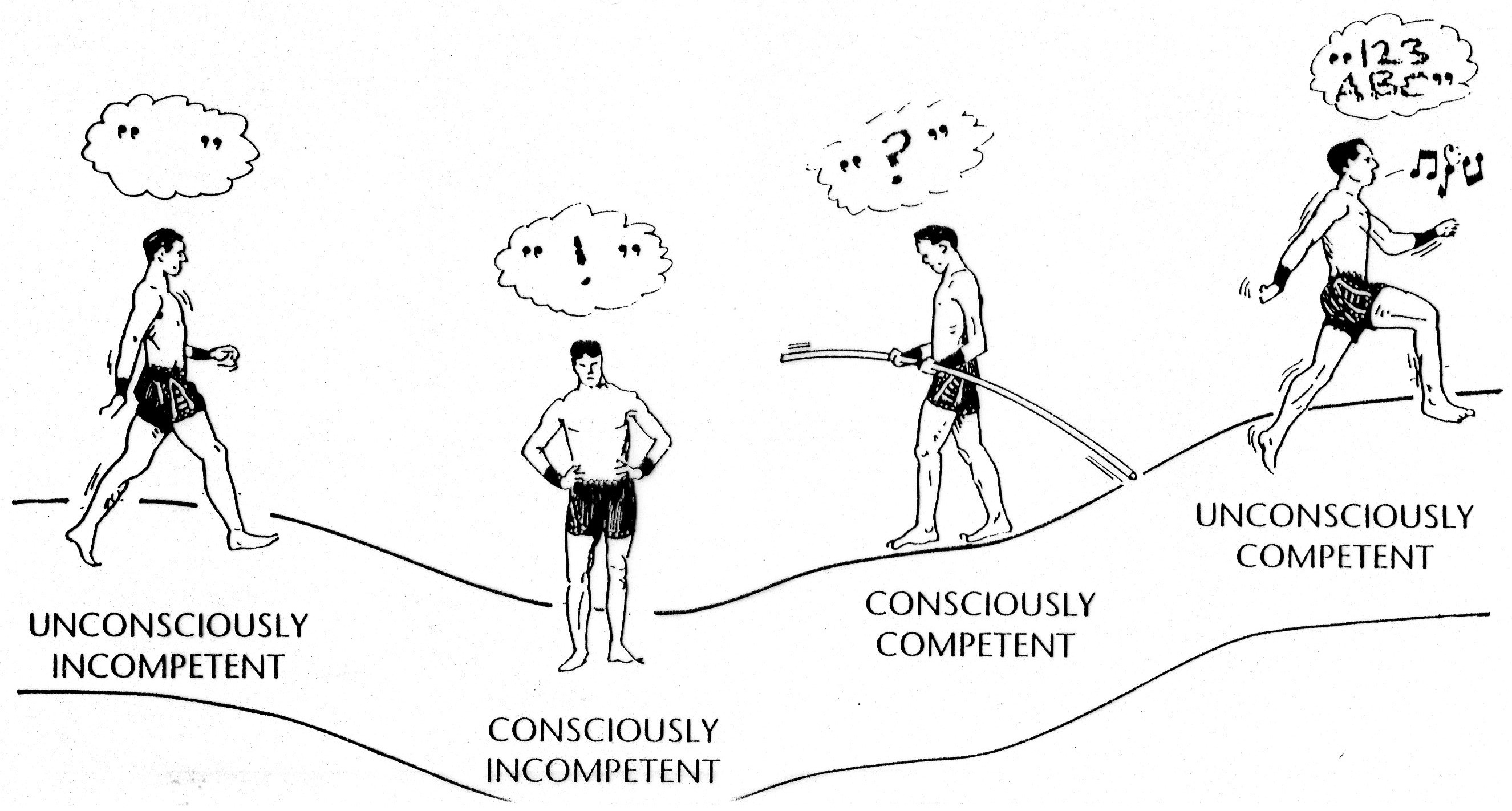

What the cartoon means to convey

My cartoon summarising the Learning Curve describes a normal process of learning or change. Humans do not learn in a straight line – from not knowing to knowing – from top left to bottom right of the Johari Window. Emotional blocks appear as we become faced with the enormity of what there is to be learned. We question our own abilities and, quite often, the abilities of our teachers/parents/friends etc.

Please note: the term ‘incompetent’ used here is not intended to be an insult. It simply saying all of us, including me, do not know some important things or we do not possess some valuable skill. We are unaware of them; we are unconsciously incompetent. The cartoon suggests we can go through life happily if we are blissfully unaware of the learning we could do. Obstacles to learning can make things sticky when we start to make the effort to change. We become aware of what might be possible – and then the going gets tough.

Before I can learn, I need to become aware of what I do not know (consciously incompetent). This is the discomfort that will arise when a safe experiment feels like it’s going wrong. There will be more small defeats, than small victories. Anyone who has been on a training course or lengthy university programme, will recall what it felt like around the one-third point of that training.

The only way forward is further practise and this leads to awareness of our improving competence. Although we may feel better at that time, we are likely to remain a little unsure – consciously competent. This is well evidenced in the example of learning to ride a bike; we still fall off or falter when we think about it too hard!

It is only when the sense of uncertainty eases, we may become more confident – unconsciously competent -and ready to press on to new horizons once again (only to find the process happens all over again!).

The critical path to change is rarely direct or straight

In my experience, working on change as I drive up a motorway is not a good plan. After all, I do not even change gears so much on a motorway!

I emphasise this phenomenon as it tells us that the pathway to understanding and improvement follows a scenic route. We need to take this into account when planning our own learning and designing the next round of experiments. Rushing into things can be counter-productive. We may need to take more time than we anticipated to AN move from a-to-z.

AN EXPERIMENT

Take some time to recall some training you did, a short or long time ago. Note down one time when it seemed difficult. It does not need to be in ‘school’; it could be in work, at home or in your community.

How did you react at that time? Maybe you gave up the programme? I did on one occasion!

Maybe you talked to other people or maybe you worked extra hard?

What was the outcome of the steps you took? Were you pleased or did you regret something?

In retrospect, what might you have done differently, if anything?

Do these thoughts highlight how safe experiments depend on your approach to the task? I can point a finger and make suggestions, but none of that works without your active interest in re-designing, repeating and observing what goes on.

That very conclusion can, itself, be a source of irritation; you are having to do all the work!

When I work directly with people, my contribution is to help the other keep focus and to benefit from my experience and knowledge of experimental design in the real world.

If I am helping here, with my website, please let me know. If not, please tell me what’s getting in the way. That’s another experiment; you can take time to gather your thoughts and send them to me – it is not obligatory, but it may help both of us!

A SAFE EXPERIMENT around how I learn: Stop, for a moment, and pay attention to how you feel now; are you curious about the material you are reading? There could be an important sensation associated with this experience.

Use the illustration, above, to locate your place on the learning curve now. Also, consider some practicalities. Are your eyes tired from reading; do you feel laggardly from a lack of exercise? If so, what might you do differently; take a rest now or do something else?

One other step you can take is to develop a practical approach to relaxation. There are several things you can do to benefit from relaxation. There are DVD’s and CD’s on the internet that can help but it’s tricky to ensure good quality material. Also, specialist classes in Yoga in your area might help, but this web site focuses on what is do-able today, in your own home.

ANOTHER EXPERIMENT

Choose a good time to practice when it is unlikely that you will be interrupted for around 5-10 minutes.

Relaxation and breathing experiments will get longer as you experiment with a range of extra skills such as managing your posture.

- practising a range of breathing strategies. For example, try breathing out for a little longer than you breathe in.

- becoming more familiar with BODY SCAN and your growing sensitivity to the thoughts, feelings and sensations that you will observe.

- increasing your confidence in your ability to focus on, or just notice, internal experiences, as well as focus external objects such as sound, changing lights and the touch of your clothing.

- moving your attention at will. Instead of being dragged to an experience, you will learn to attend to a range of experiences – your internal dialogue, the pattern of your breathing, any body tension and other sources of information about your current state of body and mind.

- use of eyes, including your ‘inner eye’, to allow yourself to create images around a fixed object. This will help you relax down and meditate.

TAKING TIME TO LEARN AND ABSORB

Use a comfortable chair, recliner, or bed: A comfortable position is important while doing this exercise. Select a place where there are few sounds or lights to distract you. It may help to close your eyes throughout the practice.

Don’t force the relaxation. There is no “right” way to do this. Concentrate on how your body is responding and use controlled breathing. to generate small changes in your experience. It may be sufficient to monitor the count of your breathing; around 3/4 in and 3/4 out.

Think about a 1 or 2 syllable word that has a very relaxed sound to it. Some people choose the word “one,” some the word “easy,” some use the sound “mmmm.” Keep this word, and take it with you as you begin the experiment.

Once you have the chosen word, you may notice a reduced Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD): systematically relax all of the muscles of your body. Start at your feet and progress up through your face. Do this by tensing a muscle and then letting that tension go. Tense up on your in-breath and let go on the out-breath may help.

As you progress you may notice an area of your body feels particularly tense. Pay extra attention to this experience and tighten the muscles in that area even more and then let go. Use the SUD measure to note any changes. If it is important, do record this information, although it will temporarily disrupt your move into a relaxed state.

If an area still seems tense take your time. Stay there for a while and do not move on. Allow relaxation to come at its own pace. As you attend to the tension, use your skills of visualisation to watch that tension depart from your body. Imagine, for instance, placing that tension on a very small feather located in front of your mouth. Blow it away from you very gently on an out-breath.

As you continue the controlled breathing, and repetition of your chosen word, remind yourself that various parts of your body are beginning to feel heavy and relaxed.

Tiredness Kills

…. as the motorway signs tell us. Trying too hard is damaging as well! Do not worry about whether you were successful in achieving relaxation. When distracting thoughts enter your mind, just notice them with, say, “I’ll think about that later”. Let your mind return to your chosen word; slowly repeat that word to yourself over and over.

Continue for 5-6 minutes. Do not use an alarm clock. When you feel it is time to finish, with your eyes still closed, sit or lie quietly for a few more moments. Then open your eyes and remain quiet. Take your time to do each and every step.

With practice, relaxation should come with little effort. Practice once or twice daily but not for 2 hours after a meal. Digestive processes seem to interfere with the relaxation response.

Once you are well practised, you may find that you are able to relax in stressful circumstances by giving yourself a few moments to relax your body, concentrate on your breathing, and focus on your chosen words.

Some leads to follow

Designing small, safe experiments