What follows is not a spelling mistake: I cannot not behave. All actions are behaviour.

Whatever I do is ‘behaviour’ to a psychologist. OK, there are obvious behaviours – walking down the street, eating a meal with the family – these are visible actions. There are internal behaviours that go on 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Breathing is one;

Just noticing our sensations is another.

Feeling is yet another experience we cannot not do – even if it is a struggle to give it a name or say what the level of feeling is, NOW.

Noticing these last experiences are less obvious actions; do we notice such useful ‘doings’?

There really is no small, safe experiment without the very ‘first experiment’ of just noticing something. We can find ourselves left in a blind spot.

Once we’ve noticed, it’s possible to consider what kind of actions are available – to design a small, safe experiment. Taking small actions will create my own scenic route, especially when I’ve made a record of the outcome.

Missed opportunities

BUT there is the problem: how do we notice everyday things that are just too easy to miss? One of the problems presented by this website – particularly as the number of safe experiments grows – is that it becomes a jumble of possibilities. I do leave you to decide on what might work for you, but it still looks random and arbitrary, and that can add to any feeling of confusion. There is little evidence available to assess the relative worth of one action over another.

There are good reasons for doing this; I cannot decide what will work for you and, anyway, I value small random acts. Even so, to help you organise things a little further, I thought it might help to produce a structure:

A summary of most ACTIONS involved in a small, safe experiment

If you like categorisation, then this exercise might work for you. Here it is:

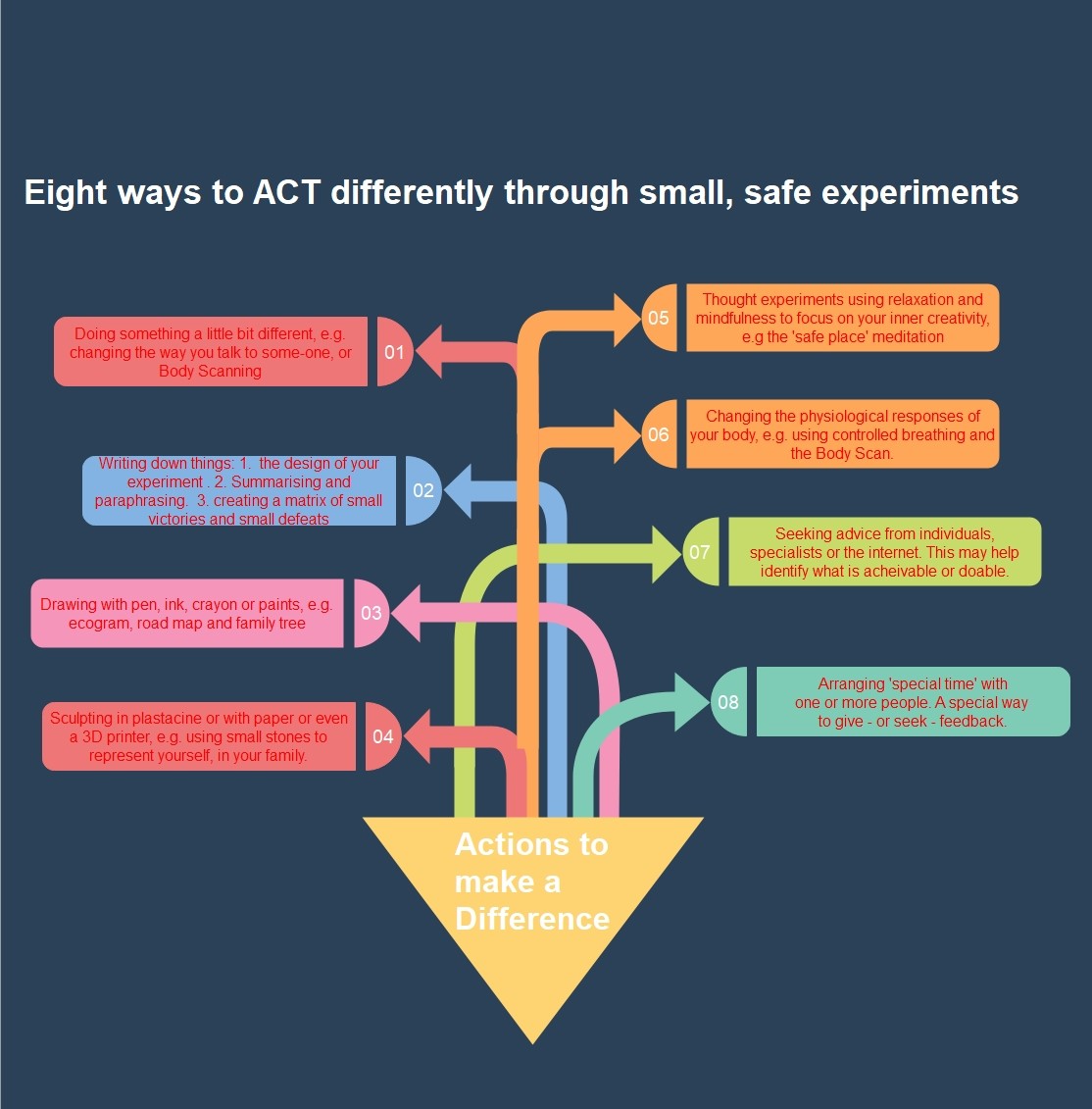

The detail in my picture is not easy to read. So here is my explanation of eight ways to categorise safe experiments; which one appeals to you?

You may find a ninth! If so, tell me about it using the contact form.

Write things down

Describe a design for the experiment, how it might move along and provide a result. Some people keep a journal, and others a diary. For me, it’s fine to use bullet-points on Post-Its, as long as you can follow the material you have created.

Draw things

… or sculpt, shape and mould something; maybe a ‘problem’ or an obstacle on your scenic route to change. Such concrete productions make a ‘record’ of what’s needed. Not everyone is fluent in art but there is no need to share the outcome of such safe experiments. All that’s needed it that you know enough about what it means and can begin to see it differently.

Thought experiments

You can imagine all sorts of things in your head. Some imaginings are troubling and others can be helpful. Thought experiments can create an inner world. It is a subjective reflection; a time when you think for yourself, in yourself and of yourself.

The Safe Place experiment is intended to be a good example of a ‘good’ outcome. You can use meditation to give advice to yourself; going into your safe place may provide the opportunity to invite in your ‘sage’ or wise person to ‘talk’ to you. You are in illustrious company when you do this work; Albert Einstein obtained his inspirations for Relativity theory from his thought experiments! There was no other way for him to make the leap of imagination that was needed.

Another thought experiment is ‘rehearsing’; that is, using my imagination to anticipate the obstacles on your scenic route in order to STOP, LOOK and LISTEN in order to consider potential solutions. Imagining those possibilities, even if they are not needed, can help us become creative and curious; to react just that little bit quicker, and get a result that might otherwise elude us.

Get advice

… from other people. This means you can benefit from another person’s perspective. The Johari Window shows how helpful feedback can be – giving it and getting it! This does not mean you have to act on their perspective; merely to hear other alternatives on offer and, indeed, to debate their likely consequences.

Keep in mind, if you would, the potential for unintended consequences when we don’t listen to others, as well as when we do listen! These are difficult to anticipate, for obvious reasons.

Self-talk

The way we talk to ourselves – inside our head – can be altered over time and with practice. Thus, our “internal dialogue” can be self-critical and negative. Affirmation work can impact on this and alter our balance of positive and negative thinking. This works even better if we attach matching actions to our thoughts. Compassion informed therapy has a lot to say about how we might relate differently to our Inner Critic.

Diversions and Distractions

Many safe experiments do both these things. For instance, controlled breathing has direct impact on your body responses and, at the same time, it is a distraction from thoughts that obstruct your drive to better mental health.

See the experiments on anxiety for more on this topic.

Music and Movement

This has been an important part of therapy for many years. Music therapists are spread thinly, but offer a values service to schools and organisations. Movement has always been a part of several therapies, but it is now seen as a therapy, in its own right. We have talking therapies, and now there are walking therapies, touched on down this page.

Any-one who has seen the late Desmond Tutu, former Archbishop of South Africa, will know how he benefitted from movement, particularly in the presence of others. I say more about him here.

Therefore, it is possible to design a safe experiment when doing ordinary things; walking around your garden, walking to the shops and decorating a room. Can you value actions that might, otherwise, be a bind? In my own case, that was so, given my own difficulties with timing and pacing.

Can you just notice the impact on your body of small, unremarkable and everyday actions? Through just noticing are you able to view any other behaviour differently? Can mundane actions create personal benefits that you might miss?

Another simple safe experiment is to join the Sing Your Heart Out (SYHO) movement who may have an active group working in your area. Their groups offer singing AND movement!

Acts of Acceptance and Committment

These are processes to help identify your options and to distinguish between what can be changed (and to accept what cannot be altered). The Desiderata has something to say about that. This poem, and my comment, is to be found at the bottom of this page.

Committing ourselves to focus on the do-able is a life-time set of experiments. There is a whole page on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). In similar vein, there are specific possibilities highlighted on this discussing Compassion-focused therapy (CFT).

Changing ways of talking to others

Our communications with others can be adjusted by a realistically-designed safe experiment able to identify do-able small steps, e.g. editing habitual ‘sorry‘ statements and removing ‘try‘ or ‘why‘ questions out of our conversation. A special case of seeking advice from others is to organise some ‘special time‘: choosing to ask some-one to be with you for a fixed amount of time in order to talk something through.

It’s possible to involve several people but ‘special time’ can easily deteriorate into more of the same old; hence the need for a realistic time limit. Another way to talk with others is through brain-storming. This ‘experiment’ generates a lot of ideas around an issue. If you use ‘brain-storming’, bear in mind that anything goes at first; zany is good. Only sort and filter ideas afterwards – not during the brain-storm.

Such ‘special cases’ could be labelled ‘feedback‘ – specifically asking other people to comment on something that is important to you. It enables other people to be ‘in your shoes’ for a moment and, indeed, you can return the favour sometimes!

Summarise and paraphrase

This can be done in our head, or in writing. During and after any small, safe experiment it can help to stand back and look at what you’ve got.

Assertiveness and fogging strategies work best in small chunks! This can be done by a pithy summary around what you now know. Can you put your conclusion in one short sentence with very few words? If you can do this, write it out, leave it for a time and come back to see if it still makes sense.

Alter your understanding if you want, especially if it creates an interesting question about this afternoon or tomorrow.

All these steps involve taking action: the middle box in the inverted tree diagram emphasises ACTION. Doing something just a little bit different is fine – it does not have to be a large or grand action, e..g. listening to another person differently is enough, if not necessarily sufficient. Beware of efforts to tightrope over the Grand Canyon.

Let me finish

… by asking: can you spot the categories that are not here? How would you categorise the experiments you have designed? It might be easy to assume I have created a conprehensive list.

How much does this categorisation help or hinder you in your design and implementation of small, safe experiment?

Further lines of enquiry

More on how to design safe experiments

A first nudge: the inverted tree

Setting out on the scenic route

Models of change that may help