Coming, going and returning

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” in the Four Quartets originally published 1943

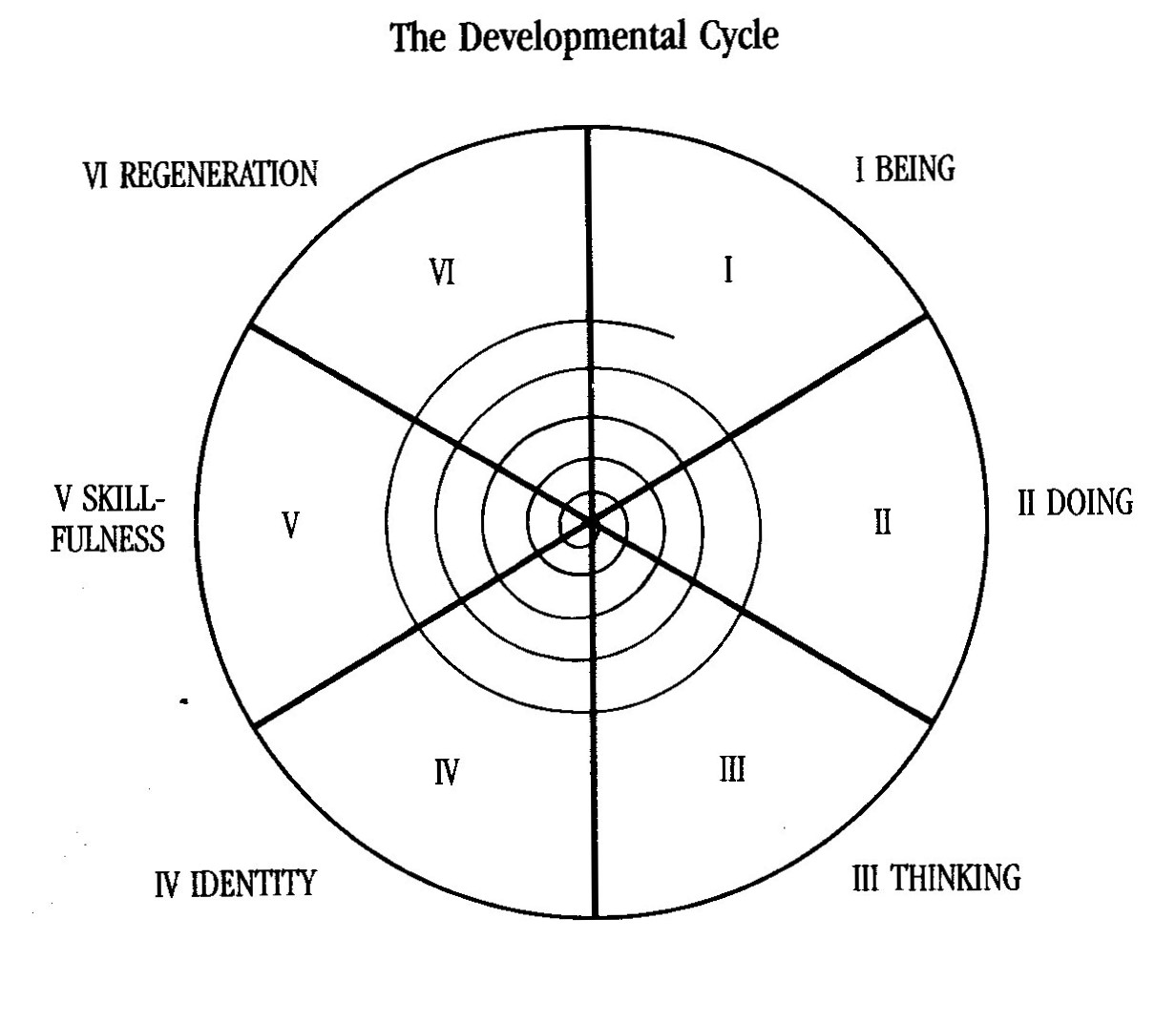

The opening illustration is taken from Pamela Levin’s text: Cycles of Power

I wonder if she had T S Elliot in mind when she was inspired to write her book? After all, he was born an American as well. Both seemed to share a fascination with Time.

Pam’s book focuses on how humans grow and develop over the decades. It is relatively old now, but no less useful for that. It was published by Health Communications Inc in 1988.

Levin offered a different ‘slant” on the process of human growth and development. Part Three of her book is explicitly given over the ‘exercises’ to learn from her material; safe experiments, maybe?

Earlier approaches – the psycho-analytic and psycho-social models – prevailing in the early 20th century – were ‘stage’ models that described a given path from our birth to adulthood and into death. Elsewhere in this web site, you will see how I summarised the work of Erik Erikson as a traditional but still helpful example of that approach.

The relatively inflexible perspective of the ‘stage’ models has now given way to the different view of ‘cycles’ of change.

A different Scenic Route

In Cycles of Power, Pamela Levin focuses on the idea of ‘return’ – she acknowledges that a cycle of development can come and go, until it completes itself, only to start over. This is an optimistic approach suggesting that “everything comes of itself at the appointed time”, to summarise the words of the I Ching.

It fits well with my own view of a scenic route where the road to change is not in a straight line and we learn both from our successes and our defeats. There is no need for a single ending and you can change your destination as you move along.

So back to the illustration from Levin’s book. She identifies seven cycles of development, as drawn. The ‘coil’ in the middle begins with our conception – at the very centre of this circle – and progresses beyond our birth toward our death. The coil is a helix moving from Centre 1 and progressing to the Outside VI.

Progress is not a straight line, it is scenic, and it does not proceed just once around the circle.

So what are the features of each cycle of development?

There is an age-related aspect to each cycle – as well as common features arising during each cycle. Those features, or patterns, are not ‘set in stone’ but its worth keeping an eye out for them. The outcome of a small, safe experiment may be more impactful under one set of circumstances, and ‘lost’ at another time.

That is why PACE is a key feature in implementing any safe experiment – look for Cluster Three on this other page.

CYCLE BY CYCLE

BEING: there are few boundaries visible

When carer and child seem as one. The mouth and feeding are at the centre of things. This may be the nearest thing to simply being in NOW, in the present. In later cycles being fed is still a theme but it can get sophisticated – fed with physical and emotional attention and simply being wrapped round one another, as lovers often do. With good fortune, we can be immobilised without fear.

When, roughly: at birth, early teens and twenties and sometime in each decade to follow.

Common responses: tiredness and vulnerabilty, open to hurt or even ‘illness’

Characteristic pattern: periods of rapid change or growth. Notice how, in teen years relationships with peers can come and go rapidly and veer from intimate to hostile in short order.

Possible safe experiment: something that takes you beyond any self-imposed limitations. This means identifying boundaries and testing them. What alternative nurturing is needed to help step over the line and move on? Notice, by the way, how the Window of Tolerance requires you to step over and keep on starting a ‘new’ journey.

DOING: knowledge comes from action

An ancient safe experiment put forward by the Greek, Sophocles.

When: roughly begins at 6-18 months and early teens and twenties as well in intervals of 10-12 years thereafter.

Common responses: needing stimulation, yet feeling nurtured enough to leave and get other things done.

Characteristic growth pattern: meeting new situations; sabotaging ourselves through fear or anxiety in the face of newness.

Possible safe experiments: are about restoring our capacity to do things. Completing the smallest possible sequence of change (that’s why ‘small’ is beautiful!). More, or too much, can prove indigestible. Even though these safe experiments are action-oriented, relationships that help things happen are important. In actual practice, affirmation of self – and from others – can be valuable.

A specific safe experiment would be “Editing out ‘try’ from your internal dialogue”, that is, stopping when you ‘hear’ try in your vocabulary in order to find something to do instead.

THINKING

…..when dependency becomes boring, it’s time to think about being independent and try it out for size.

When roughly around 18 months to three years and 14 years or when you become a caretaker of a two year old and/or are breaking out of a dependency relationship in early years or adulthood.

Common responses: challenge to existing boundaries, awareness of loss, threat and challenge. Here’s one from Kahil Gibran’s The Prophet:

When you are joyous, look deep into your heart and you shall find it is only that which has given you sorrow that is giving you joy.

When you are sorrowful look again in your heart, and you shall see that in truth you are weeping for that which has been your delight.

Characteristic growth pattern: sudden spurts of insight and frustration as things are tested; maybe found wanting and – other times – exciting.

Possible safe experiments: things that test our ability to see what we can control and what we cannot control. Pushing back and pushing away to create a different space for ourselves. In practice, this will involve communication with others, self-assertion, and finding out what I am responsible for. Asking for things becomes an important safe experiment. A specific safe experiment would be “Editing in ‘will’ into your internal dialogue”; that is, when your hear your vocabulary is lukewarm or half-hearted, substituting ‘will’ into any thought in order to strengthen belief in yourself to really complete something important.

IDENTIFYING

- when I attend to “who was I and who am I, now”? Elsewhere , I touch on the death of Queen Elizabeth II. For many people, not just in the UK, this event will impact of their identity – and I am not referring only to the Prince of Wales’ elevation to being King Charles III.

- When: roughly around three to six years of age and again around 15 years. Also, recycles at ages that are multiples of 15.

Common responses: changing key relationships, widening our circle of contacts and learning new roles. Boundary changes, say, towards greater independence likely. Once important response is labelled ‘individuation’ by psychologists; it is a often-protracted experience of separating out from our care-takers, and become independent adults in our own right.

Characteristic growth pattern: rapid and unpredictable. How do we know what we do not know? Experimenting and learning from mistakes, including explorations around our sexuality.

Possible safe experiments: a very concrete safe experiment here is the one where you ask- in the face of some issue or obstacle: what would [a friend, family member or any AN OTHER] say about this? Such feedback help us to live with small defeats and learning about ‘something different’ that can be done in the face of any small defeats – and how we might celebrate small victories. Please keep in mind that such changes invite ‘small defeats’; after all, how long doe it take to become fluent in demonstrating new skills.

In practice, this will include exploring the limits of our actions. This might be a time when the Ecogram and Road Map will prove useful – if only to track where we came from and appear to be going to. Later in life, it invites us to re-examine our Script and to consider changes to the narrative.

If you want a light-hearted moment, have a look at what Pop Eye had to say about who he is!

SKILLFULNESS

This cycle is not just about practical things, such as “how do I do that“. it is a cycle of contemplation on values and morals, where we learn to argue and wanting to do things “my way”.

When: roughly between six and twelve years and when parenting a child aged between 6 – 12 years, or multiples of that time interval.

Common responses: changing identities once again, forming options and implementing decisions about the direction of my life.

Characteristic growth pattern: learning and practising new ways. Good time for designing and implementing challenging safe experiments.

Possible safe experiments: ways to explore our world a little bit differently; ways to test our thinking, even if it feels clumsy from time to time. Being more able to see how or emotional landscape is important. I would say Tara Brach’s 10 minute RAIN process is relevant to this cycle; it’s about feeling and action – about being compassionate to self and others and yet able to act on our feelings.

REGENERATION

When: this comes around, roughly 13 years, through 18 years, and pretty much every decade thereafter

Common responses: although Pamela Levin connects this stage to our sexual identity – our orientation, performance and relations – it seems to me it is about ‘completion’ of a many things. This includes honing skills and making and sustaining relationships of many shapes and sizes.

Characteristic growth pattern: transiting and transitions; a time when seeds are planted and evolve until they come to fruition. A slow and steady change, but often with a sudden ending. it some ways, it is a revisiting of each stage in order to move on. Stagnation may arise if regeneration does not happen (as Erik Erikson said in a more traditional model of human growth and development).

Possible safe experiments: a time for revising the Road Map and Eco-grams – where did I come from, and where do I appear to be heading? Also, consider following a pathway and noticing how you stay on the scenic route. Ask yourself: in what way am I responsible and how do I show that? Also, it is a time to take stock.

RECYCLING

When: this process begins, roughly, around late teens and most decades there-after.

Common responses: curiosity and distractability. Testing and breaking limits. Rebelling and resisting.

Characteristic growth pattern: changeable, prolonged or fore-shortened (who knows?).

Possible safe experiments: ones that help us attend to the human condition in a more subtle way; learning from mistakes and demonstrating a willingness to let go. This may be needed when I am facing losses in my life. Of course, the instruction is easier said than done. Indeed, it can be counter-productive to think this can be done today. The pathway to it is elusive. Consider, once again, the words of Kahil Gibran:

You are not enclosed within your bodies, nor confined to houses or fields.

That which is you dwells above the mountain and roves with the wind.

It is not a thing that crawls into the sun for warmth or digs holes into darkness for safety,

But a thing free, a spirit that envelops the earth and moves in the ether.

Kahil Gibran The Prophet

IN SUMMARY

So why do I like Pamela Levin’s cyclical model? I trust my lists have offered a number of leads to help with the design of small, safe experiments by:

- showing we can solve problems and provide confidence in our own ability to do this.

- we may not do things well all of the time, but we can walk toward our ambitions. Cycles of Power is a model that fosters curiosity about our experiences.

- Pamela Levin’s attitude, in my opinion, values the safe experiment of ‘just noticing’. It accepts the need to become aware of discomfort and face up to each discomfort.

- it respects that we can act, rather than respond. Even so, it respects that there is a time for not acting, but simply being. This notion of ‘being‘ is well illustrated by the poets included here, on this page.

- it helps us to understand that ‘looping’, that is, our ability to go round and round and get stuck from time to time. It helps us to accept the value of waiting in a queue for the right time to come around and when to act decisively.

- it is a model that help me to distinguish small victories from small defeats and gives me confidence to find ‘something different’ I can do.

- it shows we can do things – we do not have to wait for some-one to help us along.

- at the same time, it helps identify the limits of what we can do and, indeed, not do.

It starts to make clear the aims of the SAFE EXPERIMENT; that is:

- To unstick our physical and emotional energy tied up elsewhere.

- To identify and attend to our range of feelings.

- To find ways to repair emotional and psychological injuries.

- To identify and manage the limits we place upon ourselves.

All that said, please keep in mind that all these illustrations can only be maps. How you walk through your own territory is another matter.

Other leads to follow

How to design safe experiments