I’ve been reminded that a picture paints a thousand words. Therefore, can some illustrations help explain My Way and will pictures help you design small, safe experiments?

This is a helpful request as the web site is now too full of words. That is not something to be proud of.

I am going to have a shot at summarising my thoughts in a series of illustrations. OK, I’ll be adding some more words but let’s see ……

Each illustration will include a short explanation, and then I will move on.

PART ONE: finding a direction

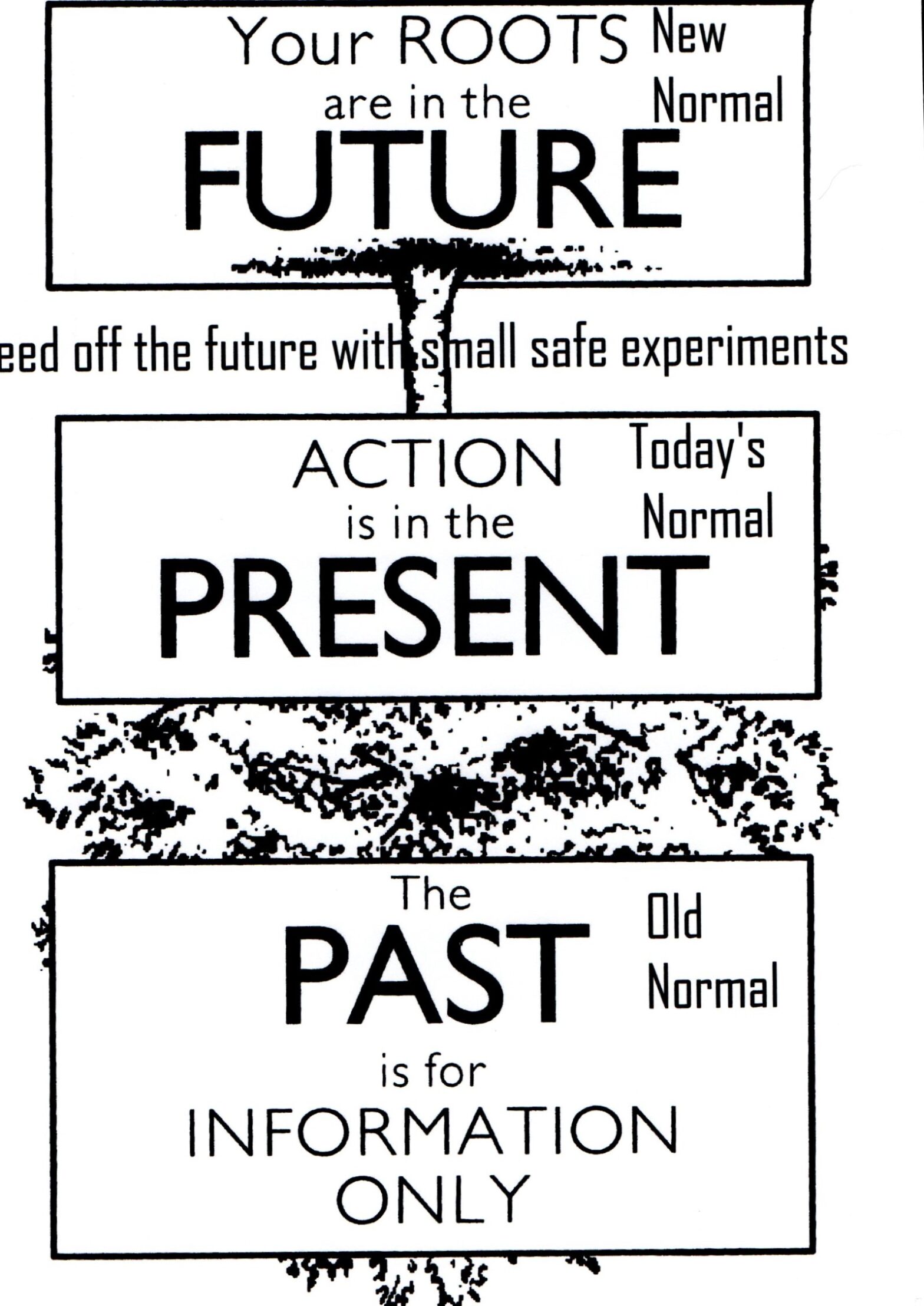

I started this page with a picture that might be familiar: it’s the ‘inverted tree’ and you might want to revisit the safe experiment attached to it.

What the picture says to me is that therapy is an uncertain journey into the future.

Actions, today, will shape that journey.

Information from the past can help us design the journey, but the focus is on a forward direction, even if there are a few diversions on the way (small defeats). In my view, traditional therapies paid too much attention to the past telling us, at the same time, that it was difficult to alter it!

Curiosity is one quality that may help us keep looking ahead (as you look from side-to-side).

Unlike trees, humans do not stay in one place to be nourished. They move about – and not just to restaurants. They need a range of nourishments!

So what route might you and I follow in pursuit of that ‘nourishment’?

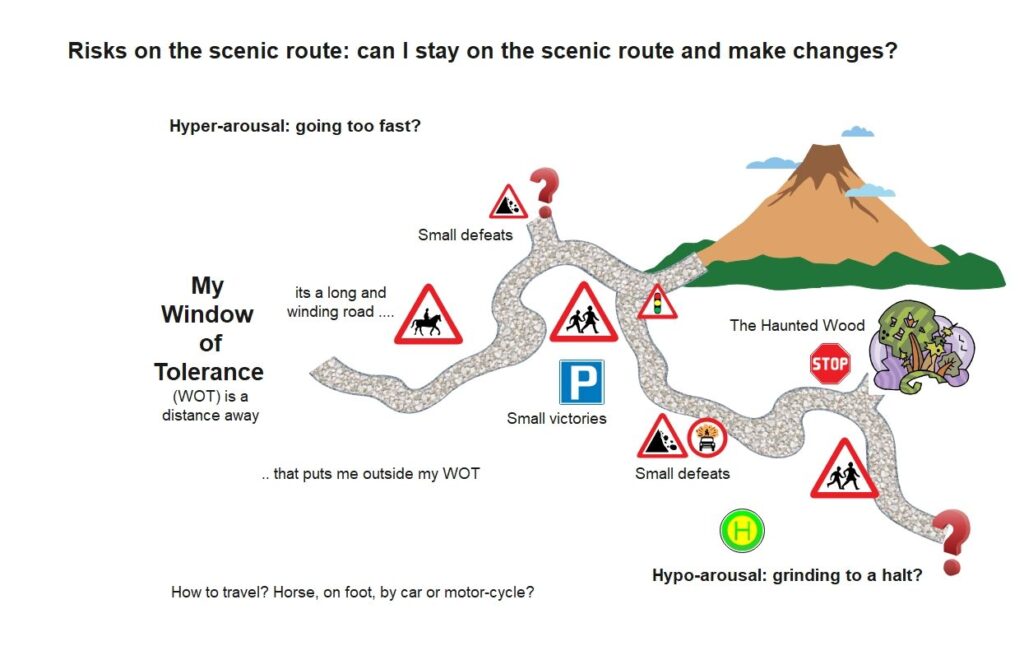

This is my picture of the overall journey viewed from above, as though from a helicopter. It is a journey that involves some level of risk:

….. so I can stay put if I feel daunted. Does the ‘haunted wood‘ suggest something daunting? what things haunt you in your life?

Consider what your belief, here, tells you about the meaning you make about the world in which you presently live?

If I move on out then I am taking the risk of testing my map reading skills.

Learning from small victories and small defeats

There are at least two classes of small defeat I might face on my travels:

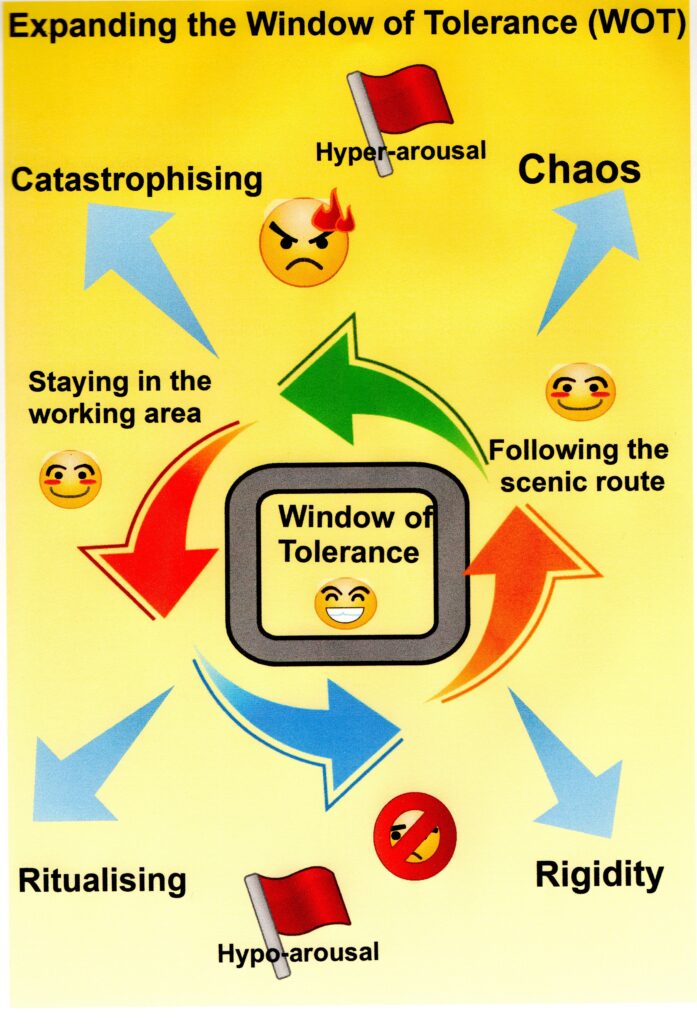

- one is hyper-arousal – when the change seems too much, and I panic.

- the other is hypo-arousal – when I overwhelmed at the prospect before me that I collapse under the weight of it. Although this is an unpleasant experience, this is the body’s way of saying: just hold it there, for a moment!

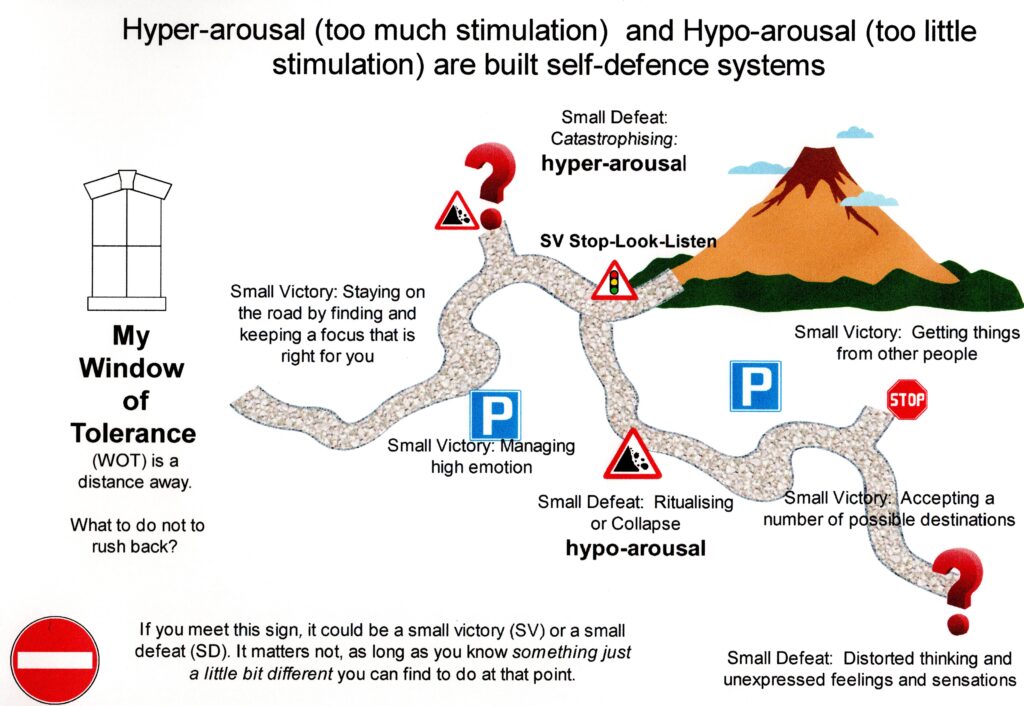

Two responses associated with hyper-arousal are Catastrophising (such as: that was a waste of time, why do I bother?) and Chaos (Arghhhh). The two associated with hypo-arousal are getting stuck and Ritualising (such as: this is the only way I can get do things) and Rigidity (Beam me up, Scotty).

At the extreme, hypo-arousal promotes collapse and fainting.

In both cases, I can benefit from Stopping, Looking and Listening for a moment.

There is no obligation on me to change. True, there will consequences for me – from journeying, and from not taking that journey.

Which is it to be, for you?

Starting on the scenic route

When I begin my journey, and step outside my Window of Tolerance (WOT), I am inviting change. On my trip I can meet small victories, at the Parking signs, and small defeats around the Red Question Marks dotted along the route.

BUT my journey does require me to step outside my Window of Tolerance (WOT) and to set out on a Scenic Route, a sort of Yellow Brick Road, to somewhere different. The journey need not be a marathon or a sprint; indeed, I emphasise throughout this website that problems arise when I rush into things.

Indeed, the illustration, above, invites me to consider my form of transport if I am to avoid extreme responses. Anything that speeds me up is likely to increase my risk. Adapting to change is usually a slow process. Time is needed to assimilate what is going on. Riding on a 1000 cc motor cycle may be tempting, but, in this case, it is less likely to get me to a destination safely.

Riding a horse or walking along my chosen route is, generally speaking, a safer bet.

Safe experiments are small and well informed steps enabling

When I meet an obstacle on the road I may struggle to step around them. I can over-react and find myself propelled to an extreme response.

Working with the Window of Tolerance (WoT)

Here is another view of that journey:

I will face a number of risks on my journey. Some are real threats and others have the appearance of a threat. Thus, a No Entry sign may suggest danger but, as a walker, I may find it is a useful short-cut.

These illustrations helps me ask another question: When you arrive at one of the ‘corners’ of my illustration, above, what actual responses do you notice?

Most of us develop ‘favourite’ ways of stopping ourselves in our tracks. When you most often seek change in your life, where do you tend to end up? Few of us are exempt from these characteristic reactions, so do explore your own ways of reacting to change.

Make notes about how you get there, and any other pattern that has helped you to get there in the past.

Now I want to look at some of the obstacles – the ‘rocks’ in the road – in a different way.

PART TWO: making the first of several moves

What prompts a seemingly unsteady start? Our bodies and minds appear to have a mixed view of change. On the one hand, we want it and, on the other, we are suspicious of it. We oscillate back and forth between ‘go’ and ‘don’t go’. Thus:

I start from my present normal on the far left, above. I walk on. Troubled by what I see ahead of me, I falter and start to question my own wisdom. Under pressure to do something different I tumble into some change. In this illustration, this 0 – 60 mph response mentioned above is ‘chaos’.

However, calling on all the resilience, creativity and curiosity I can muster, I am able to identify a way forward. I develop greater self-confidence and move on. New ideas and actions are put together with old skills until I master my own New Normal (at the right hand side of the illustration)

Now what makes to pathway difficult? It appears that our bodies possess a ‘negative bias’; we possess a built-in uncertainty, sometimes called a ‘conservative impulse‘ – a wariness of risk and change. That impulse can put me on alert.

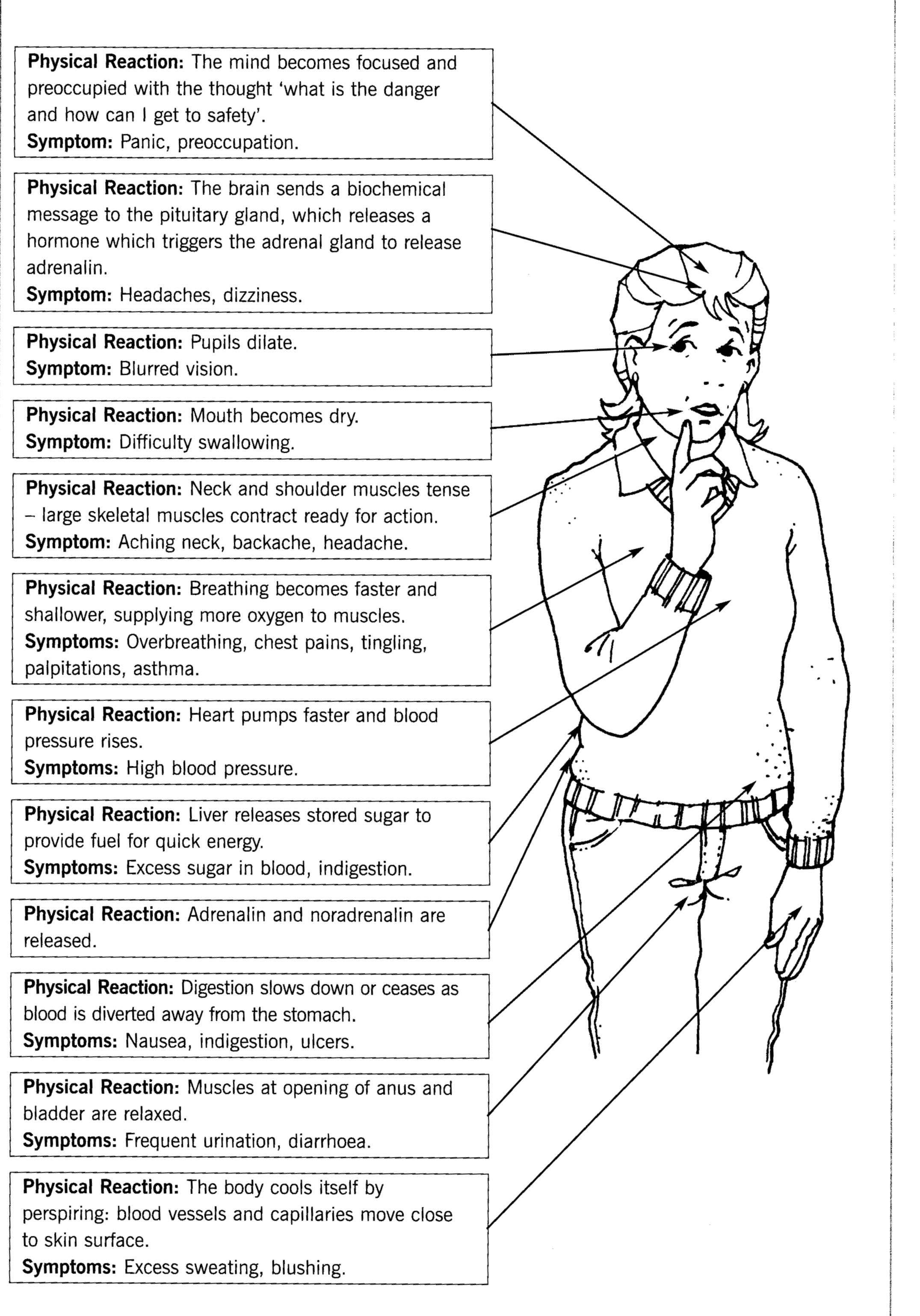

Being on alert is closely connected to feeling high emotion.

The body’s response to high emotion

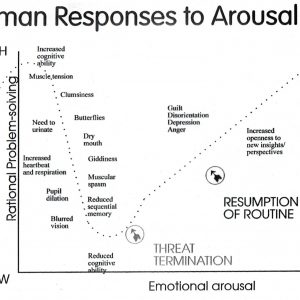

High emotion, particularly anxiety, has some predictable impact on us, as follows:

It is possible to think we have little control over these body responses.

These bodily reactions are so hard-wired into us that it is possible to predict how most people will respond, most of the time, when the going gets tough. When difficult things happen, our life is disrupted by events – often by unexpected and shocking events.

A common human response to such events is as brief period of greater efficiency arising from gaining focus and giving attention to detail – only to be followed by a ‘collapse’ in the system.

It may seem from this that some things are simply beyond my control. Indeed, this is so for many; world events are out of my control as 2022 so well demonstrated. Even so, there are do-able things I can try out as long as I have enough wisdom to separate out what is achievable, from what is not.

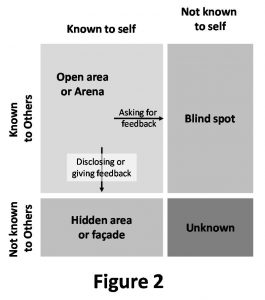

In fact, I have abilities and qualities that are sometimes hidden from me.

The Knowns and the Unknowns as seen through the Johari Window.

This illustration offers another view of the therapy journey – from top left, where things are known to us, and others in our world, and we progress toward bottom right, where things are not known to me, or others.

However, that journey is not a straight line; it is one that shifts from left to right, and back again, according to the information we give to others and, indeed, the responses we get from others. The trip into the black box at bottom right – where things are not known – is best completed on foot, as I have mentioned – not by Jumbo jet.

I find this illustration helpful as it highlights the value of other people in helping us shape our future. We hide part of ourselves from others and we are unaware of ‘parts’ of ourselves that others can see. It’s pretty handy to practise the art of sharing just so much of ourselves with other people and listening to things they have to say about what they see when we meet.

To continue: I return to the bodily responses mentioned above. We do have some control over the way our bodies respond to everyday experiences. Other people in the top right of the Johari Window – including me – can help you identify ways to respond a little bit differently.

This website is saying that we may have more control than is often appreciated.

PART THREE: designing small safe experiments

To help meet the challenges as I approach a New Normal, I can anticipate some of my feelings that go with the steps I am taking. I can develop skills that will help me. After that, I need to practice them and improve my ability.

The next illustration identifies just a few things I can do. For a start, I can manage my high emotions just a little bit differently using the three strategies printed in green:

The web-site is devoted to detailed discussion of each of the three strategies printed in green, and you might want to investigate them more in your own time starting at: what is a nudge. Also, there is a page on categories of actions that could be helpful in the design of small, safe experiments,

In the meanwhile, it pays to manage my feelings generated when I try out those strategies. This is important as some actions have unexpected impact on my body, as listed in the ‘body’ diagram, above.

When I am faced with high emotion, there are ‘other parts’ of my anatomy that can send me into Flight or Fight or, as will be seen, other trickier reactions.

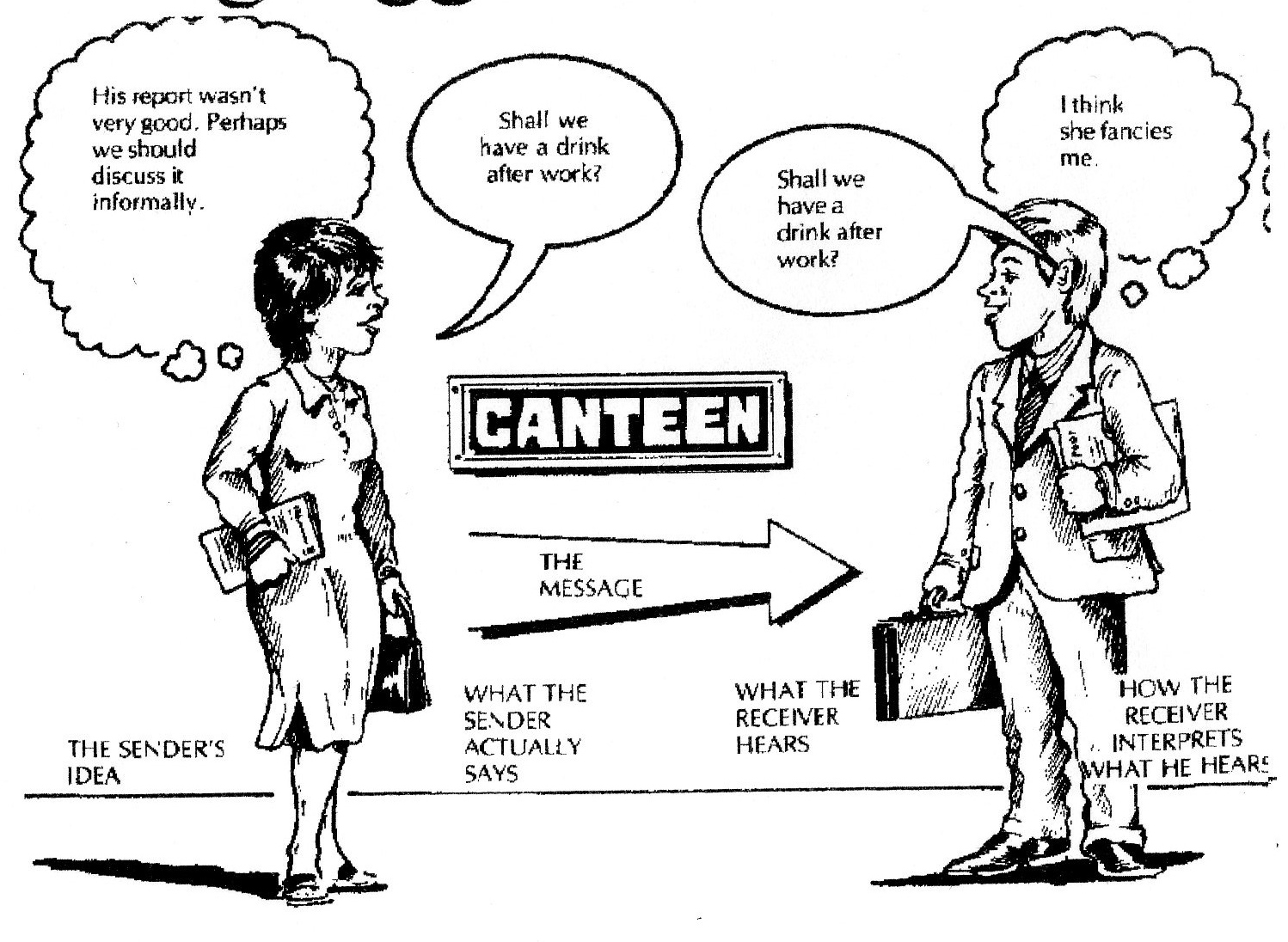

Some Talk/Self-Talk actions

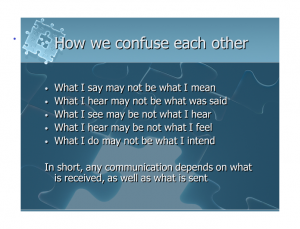

Note that talking to others can be quite a problem for us human beings; often as tricky as the conversations we have with ourselves – in our heads. For instance:

Possible ways to improve things include slowing down my delivery: saying what I say or think at a slower speed. This involves a safe experiment that involves:

- editing what I say;

- speaking in small chunks, and

- listening more to the other person rather more than to myself.

- summarising what I think I heard.

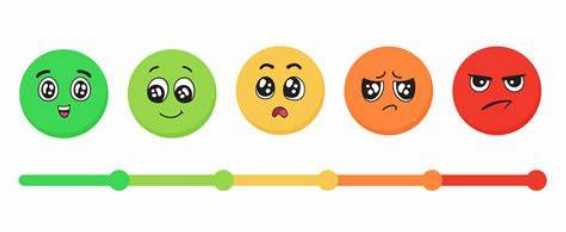

Equally important to the words I use, I want to know how I feel about what I say. Therefore, it pays to take a ‘measure’ of my current level of feeling. That measure is called a ‘SUD’ – mentioned in the illustration, above. The SUD is a Subjective Unit of Discomfort. It is a measure of your level of emotion only you can make, where:

1 = very little emotion, and,

10 = the highest level of that emotion you can recall.

A visualisation of the SUD Scoring

With 1/2 on the Green, left, and 9/10 on the Red, right. See this page for further information.

As the SUD level rises, I may find the type of experiment needs to change. For example, talking through things – in your own head – or with others – seems to work best with lower levels of emotion. You can talk things through with the support of others. As the level rises your attention may be best turned to diversions and distractions in the middle range. This will include controlled breathing, visualisation and ‘safe place’ work.

At the highest level of SUD, the way to go is ‘with the flow’. Meditation and Mindfulness works for some people but look for ‘just noticing‘ on this hyperlink as another way to Go With the Flow.

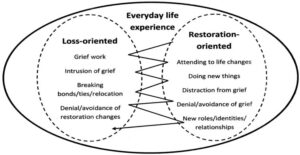

Let me end this illustrated journey along the scenic route, by offering this illustration. It offers an explanation for the frustration I may feel as I experience the impact of change on my life. There is little order in it; one day I can feel confident and the next day I feel as though any progress is an illusion.

One moment I am sad and depressed, and the next moment I can find myself doing new things and feeling good about that.

For more a detailed comment on the Stroebe and Schut view of change, take a look at the bottom of this page: https://your-nudge.com/space-and-time-changes-after-death-and-separation/

There is reason to think that this oscillation of my responses represented by the wavy line arises from the operation of my central and autonomic nervous systems. The website has much to say about this.

I’d encourage you to look at one view of our nervous system and Stephen Porges’ material as well as the information about the impact of separation and death on human beings.

If all this feels too much, would it help to consider this page?

Furthermore, you can find further information on the scenic route at.

Some other leads you can follow

How to design safe experiments

An index of topics on this web site.

Reseaching more using the Internet

There is a further lead relating to a BBC broadcast on Melancholia from March 2021.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000sy1

This made a lot of sense to me and had the advantage of quoting authorities such as Robert Burton from the Middle Ages, along with two modern interpreters of Burton’s work.

It helped put me in my place and assured me that I am not the rebel I like to think!

I do not know how long the link will last so please let me know if it fails.