Some people have expressed surprise when I say my social work training and education experience was just as useful in my present day practice as was my psychology training. During that social work training, I learned about Problem Solving (PS) strategies. I learned about their limitations when I got into actual practice.

Most of my training in the 1960’s was pre-occupied with unsuitable models – analytic models focusing on the individual and their internal experience. Such perspectives paid little attention to power imbalances and social inequalities ingrained in our communities.

Those analytic models too often looked to the past and assumed early years problems might be rooted out and those years of experience could be re-balanced. Too often this did not happen; indeed, it could not happen when present day dilemmas created concrete, serial crises.

Problem Solving in practice

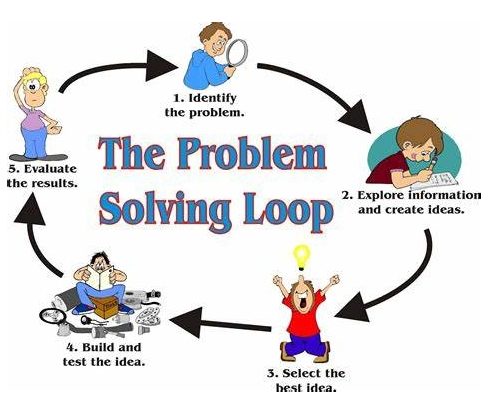

Some of my training recognized that socio-economic factors oppressed many – not all – clients. Information from Problem Solving approaches (PS), summarised in the cartoon at the head of this page, helped shape more realistic models of social work practice. I became interested in a number of models of change that are worth examination.

Those models began to foster some compassion in me when assessing the challenges imposed on clients. This perspective helped me to work with others to devise strategies that reinforced a client’s support structure. Othertimes, I was able to make connections with others to resolve problems – in relation to housing, employment and income.

In practice, I discovered that the social worker could offer more direct help as well support ‘clients’ to identify options, and how they might be implemented. Often, what was required was a sense of proportion and and a realistic assessment of what the individual client, social worker or client/social worker might achieve. In particular, it needed an attitude that did not hold the ‘client’ accountable for each and every complication in their life.

So, devising small, safe and achievable change was helped by Problem Solving Therapy (PST). It was an approach with its roots in the behaviour modification strategies that emerged in the mid-20th century.

Staying Present

One such strategy of PST is to keep focus on the present; to address today’s problems for individuals and families in difficult personal circumstances. For that reason, the ‘middle box’ in my inverted tree illustration is central to the design of small, safe experiments.

In the 1970’s this PST model was ‘translated’ into social work by William Reid and Laura Epstein. They worked in Chicago developing task-centred social work practice and giving attention to do-able solutions to specific problems. It was an active, direct and measurable approach; either something happened, or it did not.

Of course, both models had limitations and one of them went back to those structural inequalities mentioned above. Too often the ‘professional’ had too much influence over what the client was ‘supposed’ to do. It was rather too easy to impose sanctions on non-compliant clients. OK, that option was not written into many text-books, but it was an actuality. Some would argue it was necessary in situations where the safety of a vulnerable person was compromised.

Safe experiments are not ‘Homework’

The tendency to foster change in others, rather like giving ‘homework’, is still around in modern manifestations of therapies, e,g. in the cognitive behavioural models that dominate large-scale psychological services. In practice, continuing availability of service can depend on client compliance. Today the pressures on clients from health and social services systems are subtle and sanitised, but scratch them enough and you will find it.

It’s not miles away from the Government approach to ‘Nudges‘ – done to help the government. The nudges that become small, safe experiments – as far as this website is concerned – are only relevant if you design and implement them for yourself.

A structure you can use

Despite all this, you can use this task-centred framework to design your small, safe experiments. This is particularly so if the Solution-focused approach to therapy is integrated with your thinking and action. A useful framework on offer is:

Identify your Target Problem(s)

Sort options for addressing the target(s)

Set Goals in negotiation with important people in your family and community

Create and execute an Action Plan

Evaluate the results and re-assess outstanding needs.

From the results you obtain, and the meaning you make, redesign goals and re-create another Action Plan ….. to an ‘end’ or forever, if necessary!

In practice, this process of problem-solving can be summarised as:

Addressing problem orientation: Each person in the world has a unique approach to problems and it is helpful to normalise the existence of ‘problems’. Often our reactions are unusual but they are ‘normal’ responses to abnormal situations. It may help to know you are not alone when seeking to know what is really troubling to you. What’s your experience here?

Clearly defining problems: it can be difficult to identify what the problem actually is. That’s why professionals can help – as long as you know they can hinder as well.

Brainstorming and evaluating solutions: The PS approach discourages us from taking the first problem we find and the using the first ‘answer’ that comes our way. Too often it is not clear what is happening, and what can be done about it. There is a no need to evaluate problems and solutions rapidly and thoroughly even if you want to avoid cul-de-sacs or blind alleys. Instead, look for multiple solutions – even zany ones, in the first place.

Taking action: If a problem can be broken down into steps, then the problem solving process can be far more achievable. Too often a problem-solving process is stopped by an indigestible course of action. Yes, there have to be limitations to the ‘smallness’ of a step, but often there cannot be a step that is too small.

Look for the Just Noticeable Difference (JND) and go for it. Later on, actions might be larger and you may take them with greater confidence. However, the prospect of small defeats increases when the size of any step is enlarged. One such defeat worth highlighting is procrastination – putting off today, what you think you can leave until tomorrow. You ever done that?!

Notice, if you would, the connection here with the Change models I have touched on elsewhere.

Verify: it’s important to consider whether you chose the best direction of action when you first evaluated your options. How are you going to test that? This is difficult without some information – some record of your ‘results’. From those results, you may notice the balance of small defeats and small victories you have obtained from taking action. It is very easy, in my experience, to see an imbalance here; most of us work on a negative bias, so find ways to test out your perceptions. Other people can be a great help here – when you get feedback.

In many ways, I am re-hashing the design of small safe experiments, as described elsewhere. I want to do this to demonstrate that there are many ways to approach therapy. Indeed, As Lane Pederson says on this page:- little is new in therapy. So much that is available is re-packaging what has gone before.

Therefore, in addition to fostering curiosity and creativity, please consider a tea-spoon of scepticism.

Beware of lavish claims. Be doubtful about anything that offers you the world, tomorrow. Change is hard-won in my experience and, in general terms, it is not a process that comes easy to human beings.