Those of you in business may be familiar with SMART OBJECTIVES, and these are worth researching further. In my view, they help with planning small, safe experiments.

The NHS in Birmingham have an offering on this topic.

There are even printable forms to help – as long as you transfer learning from the business world into your personal world.

In brief, Smart Objectives are:

Specific: ways towards the more general aim. If the general aim is ‘to get better’, then a Specific objective may be to become physically fitter. A more specific objective still will be to walk up and down the stairs in my home on a specified number of occasions.

Measurable: to ensure that the objective can be seen to be achieved or not; in my ‘stairs’ example the objective – set by you – is either met, or it is not met. The 1-10 Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD) is not that objective but it can come into its own here.

Achievable: this is the ‘do-able’ bit of the ‘safe experiment’. Too ambitious, and it is easy to falter at the first hurdle. In my view, I doubt a SMART objective can be too small. In the example above, stairs will not work in a bungalow; it can be made attainable by identifying a given number of paces within the corridors of a bungalow.

Relevant and Realistic: you pick up the right experiment to go with the intention. If the intention is is to be fitter, then climbing stairs will be relevant for some people, say, an older person. For a younger person, something more demanding is likely to be more relevant. For some-one with a disability, some creativity may be needed. Note, here, the very individual way in which small, safe experiments are designed.

Time-bound: identifying how long you need to get a good result. That’s why some kind of recording of your results is important. It is easy to loose the thread and confuse yourself about the order of events. Climbing the stairs just once in two minutes might be good for some people, but taking ten minutes to do x climbs and descends might be more appropriate.

SMART working in my personal world

I chose ‘stairs’ as a concrete example to describe what I mean by a smart objective. In psychological, safe experiments there is likely to be a need for more creativity.

Consider the question of managing anxiety; here a specific time spent on thinking-about-breathing, and time spent on just noticing the result, and making a note about it, can be concrete, but it may not be enough. You curiosity and creativity may be called on to grasp what to do next.

Objectives, in life planning, can help us identify the more general ambitions we set for ourselves; being happy or happier, giving up cigarettes, being kinder to a partner etc. BUT these general statements take us only a very short distance.

Smart Objectives help us consider how will we become, happier, kinder or more successful.

There is a useful American book called The ACT Approach by Gordon and Borushok. You can find SMART OBJECTIVES and GOALS neatly summarised there on page 104.

By the way, I trust the ACT approach can be seen as similar in style to this web site.

It is an APPROACH to change, and less a model or a theory. In my view, it tends to over-use charts and matrices. These look rather intimidating, in the same way some Transactional Analytic drawings do, but they have something to offer – if you can stick with it.

ACT is an approach to making change in your life based on a mix of ideas from traditional and more modern therapies. It is about ACTION and recommends small steps!

In a similar way, I see other healthy developments beginning to question the ‘medical’ approach to mental and psychological health issues. The traditional approach to labelling ‘conditions’ that can ‘pathologise’ our behaviour – that makes behaviour sound ‘bad’, or ‘our own fault’ – may be on the way out. See my post on Power Meaning and Threats.

Instead, a better focus, in my view, is on how to practise some compassion for yourself and others.

A SPECIFIC EXPERIMENT

See if some, if not all, of these questions below, cast light in your life. This website encourages an attitude to our ‘problems’ by asking things like:

What do you want to change?

How might you start change? I have a section on how you might experience any change you initiate.

What might stop those changes emerging?

What resources might you need to help you make progress?

The Power, Threat and Meaning approach adds questions such as:

‘What has happened to you?’ (how has Power operated in your life?)

‘How did it affect you?’ (what kind of Threats did past events pose?)

‘What sense did you make of it?’ (what is the Meaning made from those situations by you?)

‘What did you have to do to survive?’ (what kinds of Responses to Threats have you used and, indeed, continue to use now?). in short:

Where will you find the personal power, tomorrow, to meet similar threats by altering meanings, now?

FURTHER EXPERIMENTING, WITH FILTERS

When completing the road map safe experiment, we can do so through either rose-hued or grimy spectacles. What colour are your specs? Dark? Bright? Ill-defined? A Mess? and so on.

Do the answers to the questions, above, offer you any insight into the way you see your world. What filters do you use?

The ‘lens’ we use to filter information is called a ‘world view’ by sociologists. Our world view can limit our belief in what we see and can achieve. As you view your road map, what experiences or events have shaped your choices and decisions?

What is the ‘shorthand’ label that emerged about your life; find a one, two or three word summary of how it appears to you, today? Successful? A disappointment? A race? A series of hurdles? Wasted? …. and so on.

Have these experiences moulded a half-empty or a half-full view of life in you? Go back to some earlier experiments I described, e.g. life planning your lives, your family, your jobs or career.

Use the results generated and fit more information into your road map to be clear about your turning points.

Locus of Control

The locus of control (LOC) is a world view we create over many years. It is a good reflection of the Script we have evolved. Both the LOC and Script mould the way we see things happen.

This can be altered, even if it is not easy.

Humans tend to look for patterns and causes – often when there are none. One way we do this is to sit on line between:

I DID IT —————————————————————————– YOU (or THEY) DID IT

or, as psychologists label it:

Internal Locus of Control ——————————————– External Locus of Control

This Locus of Control (LOC) can lead us to apportion blame for events; it was my fault …. it was her fault. Exploring and identifying your own Locus of Control (LOC) in given situations can be important in designing experiments for change. This LOC may well limit our ability to decide on how to be a little bit different.

Where we fit along this line will vary from incident to incident, but a tendency to sit at one end or the other seems to be built into each of us by the family and environment within which we were brought up.

AN EXPERIMENT

Consider a recent complication that arose in your life. Choose something ordinary and safe, rather than unusual and threatening, e.g. those keys that got lost or the day you were locked out of the house. Use a record to take the event apart:

When and where were you?

Who else was involved, if anyone at all?

What happened – keeping it brief, and factual, and to the point.

At the time, how did you react? Try to reactivate the memory and do a Body Scan to identify the thoughts, feelings and sensations that were around.

At the time, how did you account for the event? Reviewing it, now, how do you account or view the incident? Does the LOC vary from then to now?

Does this incident tell you anything about your own inclination to locate the control of events in the actions of yourself (Inner) or the actions of others (External)? What limitations does your own LOC place on your ability to make change?

I chose the issue of lost keys, as an example, as there are times when we ‘blame’ ourselves; after all, I lost the keys! On the other hand, what led up to the loss of the keys? How come are we so distracted? What other stresses and strains were surrounding us? Do we not put these stresses into a list of priorities; this led to that and that led to the other. In that list, do other people figure a lot or is it still ‘me’ that got it wrong!!

Doing this experiment – can you see the world in which you currently operate in a different light? You could compare the right-hand third of the road map with the two-thirds on the left hand side – your future wishes with your past history. What would have to change to ensure that tomorrow does not simply turn out to be another yesterday?

…. and other more subtle influences

Our understanding and reactions to events are shaped in many subtle ways. I was fifteen years old during the Cuban nuclear crisis, one infamous time when the world came very close to nuclear war. This was followed by President Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas, Texas in November 1963. These events, with all its contradictions (‘hippies’ full of a peace and love mantras, co-existing with the Vietnam War and the threats to Berlin from the Eastern Bloc), continue to have an impact on me.

I still notice threats to my own existence hanging by a thread, particularly any sense of betrayal (politicians do that to us on a regular basis, do they not?). You may well have similar life-defining moments.

What are they and what impact did they have? Always keep brief notes so you can return to that record to help inform some other experiments.

EXPERIMENT: What family and global events had a large impact on you? How did you respond to them at the time? How do you view them today and how much influence do they have on you now? Do those influences help or hinder your progress in your life today, now? What appears to be stopping you moving on to a preferred place?

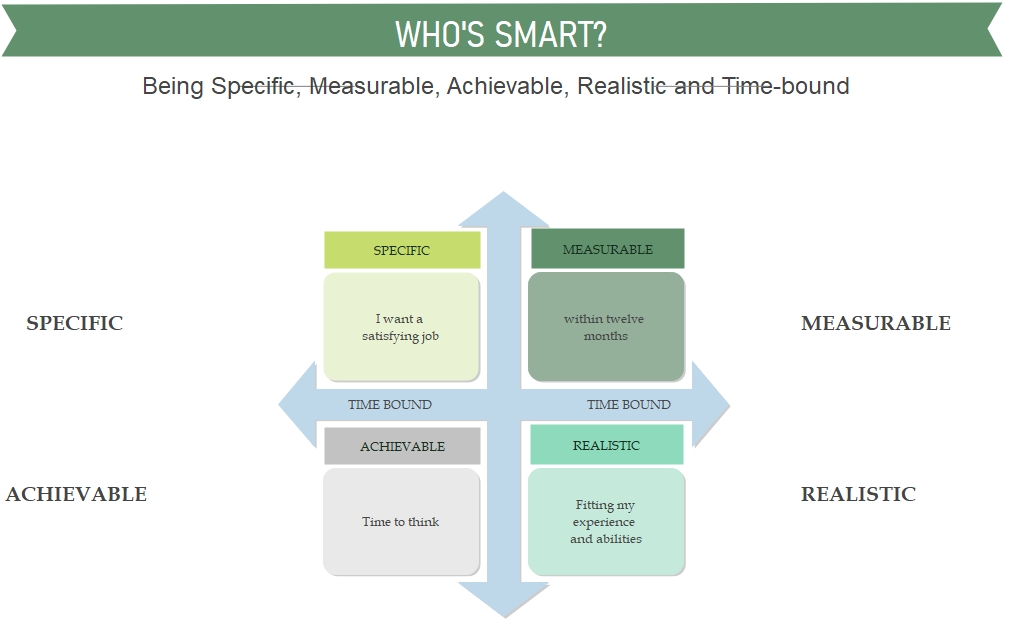

Research ways this website helps you cast a different light on the material you have generated. This visual drawn from team management may help as it helps separate different element of planning using SMART strategies. Therapy is most often a very personal experience, but there are ways that logical order, thinking things through, can still help us in the management of change, especially when groups are involved in getting things done.

A fuzzy summary illustration to being ‘SMART’

At the top, there are the guiding principles: the most general statements about your intentions. As you go down towards the bottom, more specific plans emerge until – near the very bottom – you meet small, safe experiments once again – the do-able things that take you forward one step at a time.