Dissociation: a special ‘defence mechanism’

………. and described as a “disorder of not being in the present” by Dr Peter Levine, a leading researcher and practitioner in this field. It’s a tricky disorder when you consider my inverted tree. I place quite an emphasis on being present, and acting in the present – not the past.

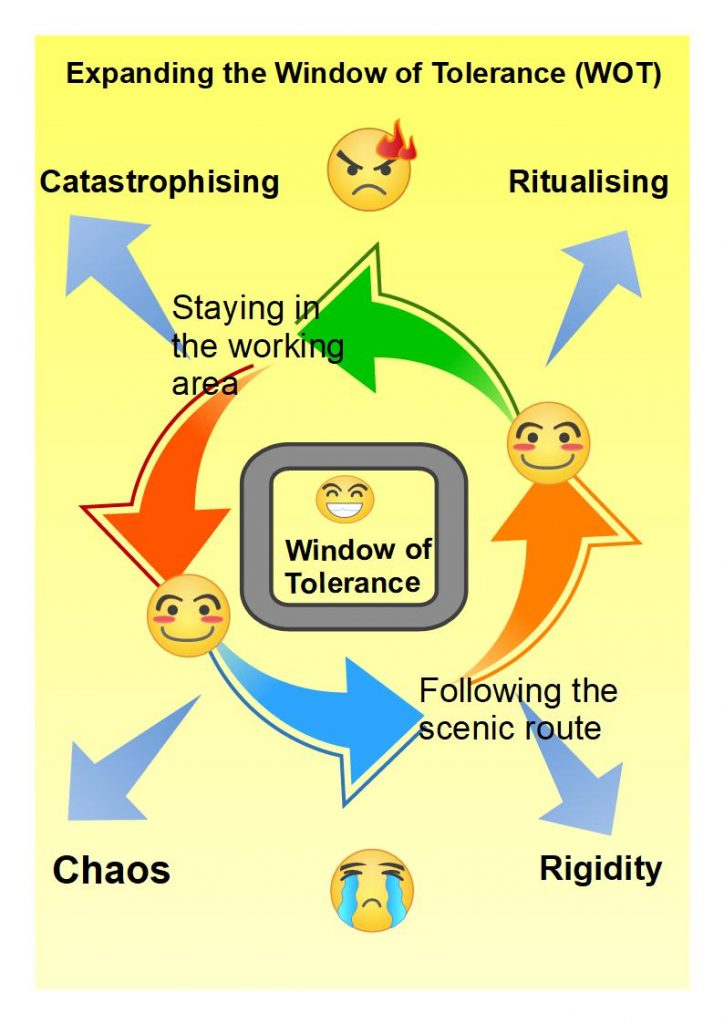

Being present helps with the design and implementation of small, safe experiments. How come? An alternative window can appear; I can look out of it and consider taking a scenic route to change that is just a little bit different.

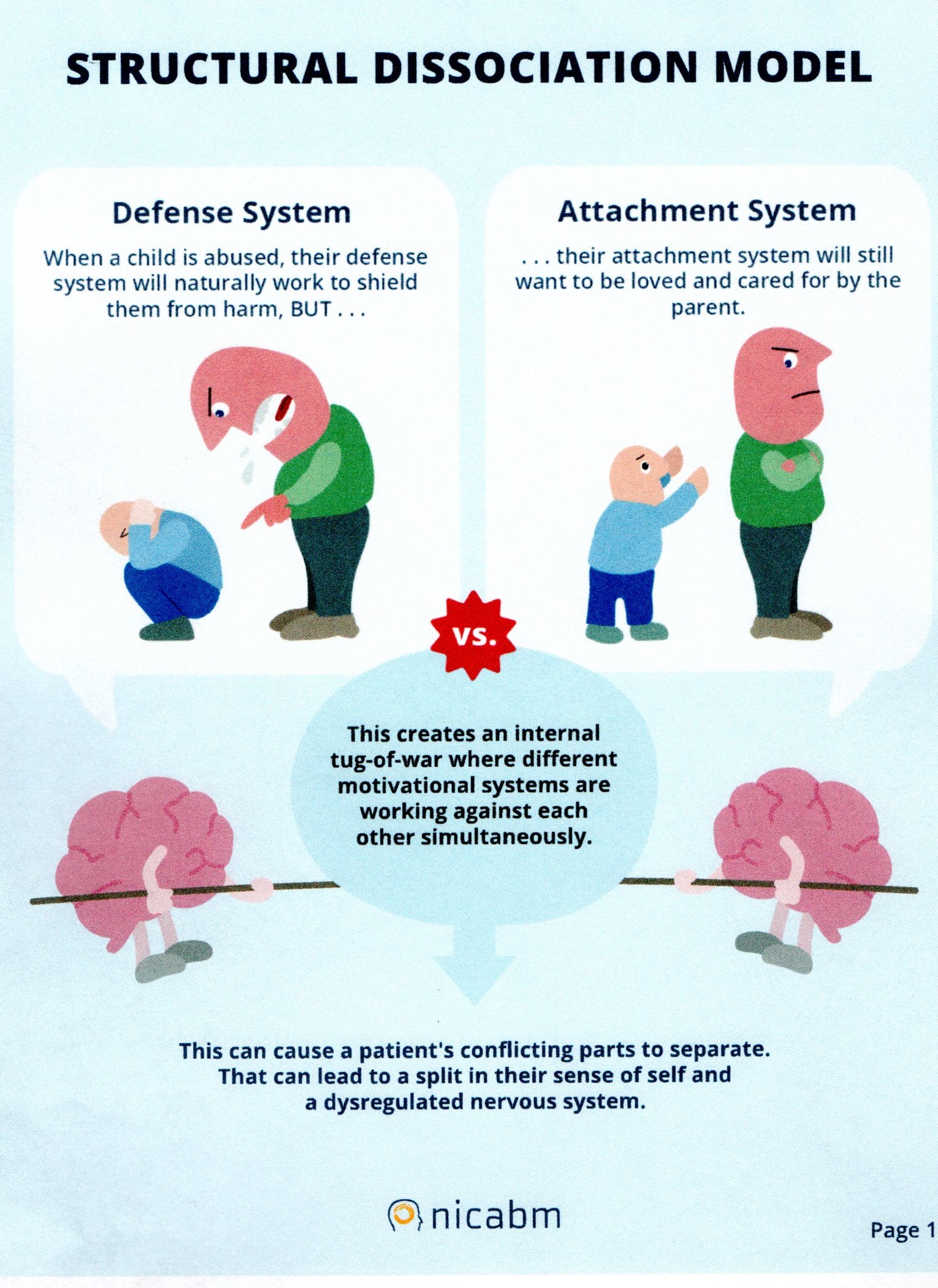

There is a process of thought involved before I take a first step. Often that first step is delayed as different ‘parts’ of myself contemplate the options available to me. They fight amongst themselves about the priorities or the direction to take!

For some people, that fight can be too much. We learn, over the years, to cut off our more troubled and troublesome ‘parts’. This can work sometimes; it may improve our focus. However, if a ‘part’ is cut off on a permanent or semi-permanent basis, then the processes of separation persist and dissociation can begin.

There are a range of dissociative responses to consider.

These are described as:

Dissociative identity: a mental process of disconnecting from one’s thoughts, feelings, memories or a sense of identity. It may look like daydreaming, spacing out, or eyes glazing over. Sometimes individuals act differently, or using a different tone of voice or different gestures. There can be sudden switches between emotions, or reactions to an event, such as appearing frightened and timid, then becoming bombastic and violent.

Many people with a dissociative disorder have had a traumatic event during childhood. The dissociation is but one way to avoid dealing with such an incident – it is a coping strategy.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is the diagnosed condition and it used to be called multiple personality disorder. Someone diagnosed with DID may feel uncertain about their identity and who they are. They may feel the presence of other identities, each with their own names, voices, personal histories and mannerisms. The main symptoms of DID are:

- memory gaps about everyday events and personal information.

- having several distinct identities.

Dissociative amnesia: this disorder can show in several ways. There may be periods where information about myself or events in my past life are not recalled. It’s even possible to forget a learned talent or skill. The symptoms can include disconnectedness from myself and the world around me; forgetting about certain time periods (hours, days or even longer), losing recollection of events and personal information.

Particularly relevant is a tendency to feel little or no physical pain. The result can be uncertainties about who I am or even an awareness of my distinctly different identities. These gaps in memory are much more severe than normal forgetfulness and it is important to consult doctors less the condition arise from another medical condition.

Some people with dissociative amnesia find themselves in a strange place without knowing how they got there. They may have travelled there on purpose, or wandered off in a confused state. These blank episodes may last minutes, hours or days. In rare cases, they can last months or years.

Then there is Functional Neurological Disorder (FND). This condition is not well understood as the body responds in ways that have no obvious organic basis; scans offer up little evidence. The neurological symptoms appear to be caused by problems in the nervous system, but they are not linked to a specific disease or physical disorder. It affects how the brain and body send and receive signals. The one seems disconnected from the other.

Symptoms of functional neurological disorder

The symptoms of FND may fluctuate, or be there a lot of the time. They include:

– difficulty moving, for example walking or controlling your arms and legs

– problems balancing

– tingling sensations or twitches in the body

– headaches, migraines or dizziness

– changes in eyesight, for example blurred vision

– pain, which is sometimes hard to locate, combined with tiredness

All these experiences are not a million miles away from features of the peripheral and polyneuropathies. The complexity of this presentation and the possible ’causes’ requires input from psychiatrists, psychologists and specialist neurologists and that’s not easy to come by!

Even so, what is known about it seems to support the small, safe experimental approach as treatment depends on each patient’s creativity and perserverance, rather than medication on its own.

Responding to forms of Dissociation

Dissociation can be seen as a special and rather mysterious condition; generally a ‘bad’ thing as it can involve disturbing experiences. However, dissociation can make sense once we just notice how it may have ‘looked after’ us sometime in the past. It can prove a ‘better’ strategy when faced with overwhelming stress, or trying to manage a situation promoting confusion, flight or fight etc.

When it is not possible to escape by physical actions, then a retreat into ourselves and a detachment from the situation make sense. Dissociation may persist and displace negative feelings in the moment. This could be a helpful action in the short term.

That said, too much dissociating can slow or prevent recovery from the impact of trauma. It is a condition that disrupts usually integrated functions of consciousness, perception, memory, identity, and affect. Persistent blanking out can interfere with everyday performance. ‘Zoning out’ is one reported symptom, falling, as it does, at the mild end of the spectrum. Some symptoms of dissociation can be part of other conditions, e.g. anxiety.

Once the purpose of a dissociative response becomes clear, it may be possible to respond to this feature more constructively. If so, how might dissociative behaviour be approached?

One aim of therapy is to increase choice and to manage experiences so there is a beginning, middle and end that feels more under control.

Identifying small, safe experiments connected to dissociation may be best developed with some professional guidance but I can comment on some practical steps that work with those ‘relatives’ of dissociation; such as:

De-realisation and de-personalisation

Derealisation: dissociation can be related to difficulty with sensory awareness – where perceptions of our senses might change. Familiar things might start to feel unfamiliar, or I may experience an altered sense of reality. It is this altered sense of reality that carries the label “derealisation”.

Symptoms include feeling alienated from others or being unfamiliar with your surroundings — for example, like you’re living in a movie or a dream. If it can feel like you are watching yourself in a movie, then you can take advantage of that fact. It is a process that is used for good in therapy when visualisation is used in an organised and purposeful fashion.

Symptoms of depersonalization include

- Feelings that you’re an outside observer of your thoughts, feelings, your body or parts of your body — for example, as if you were floating in air above yourself.

- Feeling like a robot or that you’re not in control of your speech or movements.

- The sense that your body, legs or arms appear distorted, enlarged or shrunken, or that your head is wrapped in cotton.

- Emotional or physical numbness of your senses or responses to the world around you.

- A sense that your memories lack emotion, and that they may or may not be your own memories.

There is a good chance of recovery.

Dissociative symptoms can become better managed. Separate parts of your identity can be helped to merge and become an integrate self.

SOME SAFE EXPERIMENTS

- Using your senses in any way you can to bring yourself back to reality. Sit down and describe in specific terms what you are noticing, feeling and seeing, NOW.

- Pinching the skin on the back of your hand.

- Holding something that’s cold or really warm (but not too extreme, for obvious reasons!).

- Focus on the sensation of the actual temperature around you.

- Counting or naming items in the room.

- Breathing slowly. [Where have you heard that before!].

- Listening to sounds around you.

- Walking barefoot, where it is safe to do so.

- Wrapping yourself in a blanket and feeling it around you. There are on the market, today, ‘heavy’ blankets and these seem to help with sleep and relaxation

- touching something or sniffing something with a strong smell.

Communicating with NOW

…. in short, all the safe experiments that help you communicate with now and your immediate experiences at a feeling and sensational basis.

SOME MORE EXPERIMENTS

- Safe space visualisation work.

- Dimming the lights and reducing other stimuli.

- Using sensory items to enhance smell, touch and texture.

- Lowering the voice of self and others.

- Raising the frequency of speech; changing prosody (your patterns of rhythm and sound used when speaking).

- Move: inside/outside and just notice the changes.

- Touch other objects or, if appropriate, allow others to use physical touch where it is OK to do so.

In face of threat, we respond with Flight/Fight but babies and youngsters cannot escape that way. As my header illustration shows, we seek to attach to a carer. That works until there is a problem – when the attachment is to some-one who turns on us or proves unable to be there for us consistently – for whatever reason.

Dissociation ruptures relationships

Instead, then, we can re-negotiate the ruptures created in our relationship patterns.

Even these serious ruptures – when there is an absence of some-one else to provide consistent support and care – can be faced.

HOW? By re-telling and re-building your own story or Script. Therapy can be a gift to explore ways to hold together your memories and experiences in a different way.

This process can best begin from the ‘bottom up’ – with our sensations and what sense I can make of them. That’s the Body Scan at work.

I mention the phenomena of dissociation, here, as it needs to see the light of day. It is a feature I meet fairly regularly. It is treatable: with guidance from an experienced and well-trained therapist.

I emphasise this as it is possible for other people to re-trigger unhelpful dissociative responses. Everyday conversations may, quite unintentionally, initiate these feelings and lead us to want to escape. There are everyday words that can trigger such a drive to escape. It is not possible to predict what those words might be. It is possible for otherwise sensible advice to be a trigger. The world of therapy is full of unintended consequences, and the experience or skills of practitioners offers no guarantee of protection.

For instance, there is a well-used therapeutic question that asks “what is the worst thing that can happen ……. [if this identified therapeutic dilemma were to be resolved]. I have known this potentially ‘helpful’ query act as a trauma trigger.

How come? It invites the listener to imagine the worst, remember the worst or return to the worst, as though it were yesterday. These re-traumatisations are well-known and harmful intrusions. The question, as given, assumes the other person has the personal resources to move into de-sensitisation – not at a ‘low’ level, but at the ‘worst’ level.

Skillful listening is needed to scan for language, professional or everyday, that might prove helpful and unhelpful.

Therapy is an organised and focused activity during which experiences of dissociation can be discussed in order to develop and learn new coping techniques. It is highly likely that one or more trauma memory will arise. Therapy exists to re-integrate any trauma, however large or small, into an integrated self. As long as client-and-therapist feel confident about responding to the extremes around our Window of Tolerance, I would expect memories to return AND to look them in the eye without Catastrophising or Chaos: does it help to be reminded of this illustration sitting at the hear of the work I do with people.

Through the processes of desensitisation and processing, a sense of being at ‘one’ with ourselves – not two or more – can emerge.

Just enough to set off down the scenic route once again.

thanks for info.

I am a 42 year old woman that has experience childhood neglect sexual abuse and abandonment. I have been practicing reducing my anixiety by being present and I discover that I “zone out” when I feel high stress. I figured this was somehow associated with my childhood trauma. This article confirmed my thoughts and helped me realize im going down the appropriate path for healing.

Thank you.

Hello Genevieve,

Thank you for taking your time to comment on this element of the website, Genevieve. I trust you continue to find ways to advance your own healing. There are comments on how others have addressed ‘zoning out’, and you may find them useful.

I’m happy to say more – on request.

Robin Trewartha

If readers take time to look at the chapter on Relapse in my ebook – available free on the Welcome page – you will find experiments that might help with staying present.