In December 2022 I heard Catherine Pittman discussing the working of the Amygdala in addressing fear and anxiety. She has done a lot of research in this area. Some of my original material on the impact of our neurology can be found at My Brain Hurts and there is an update at: how do you use neuro-science in small, safe experiments?

Catherine had some guidance for therapists: don’t lecture on neurology! OK, that sounds pretty obvious, but we can slip into this faced with the complicated bits in our job!

Prepare to manage anxiety (or trauma) differently

Catherine demonstrated how little information is of use without gradually relating it to a client’s actual experience. That’s only achieved through listening. Again, that seems obvious, but it’s tempting to cut corners when we think we know an answer.

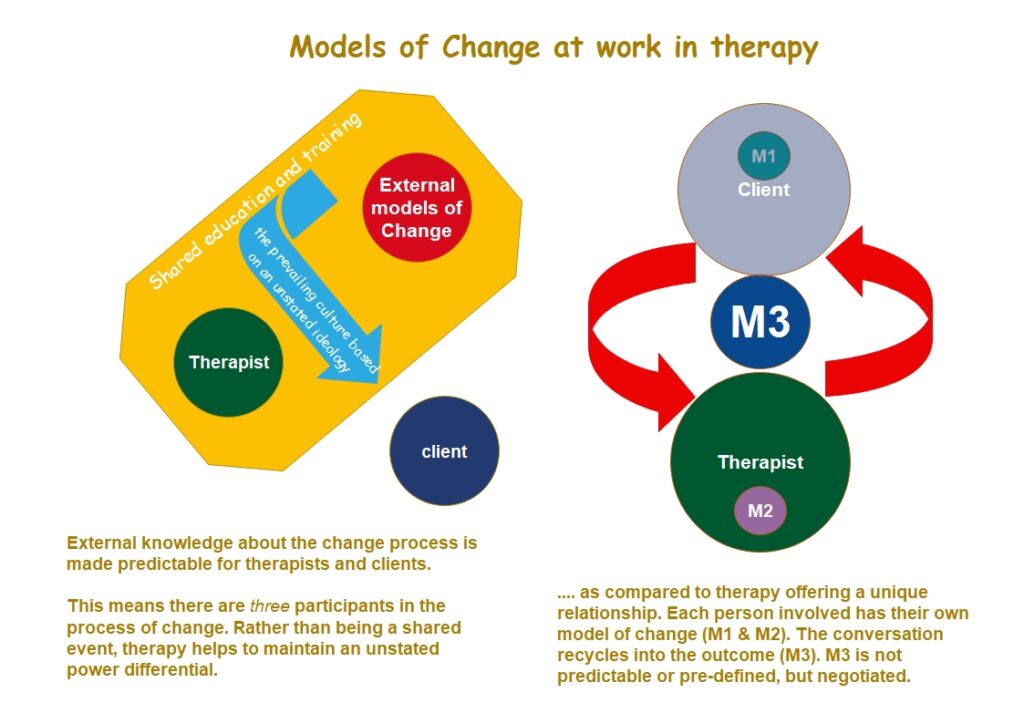

A dangerous position to take, given the commentary from the Swiss psychiatrist, Adolf Guggenbuhl-Craig mentioned on this page. Consider this diagram for the subtle ways in which we ‘allow’ information to take charge of the proceedings.

The immediate fear arising from a threat is very real to the person facing it, and to most observers. A more generalised anxiety about a threat, still real to us, may be less obvious to a third party.

Either way, our Amygdala responds to that threat intending to help us deal with the event. I say ‘help’ as it is acting to protect us – that’s it’s job. Often, for a variety of reasons, that good intention does not help in the long run. Both clients and therapists can use awareness of this – sometimes – misplaced ‘help’. When both parties are primed to work with the possibility.

Professionals are helped by a basic trauma training that asks us not start with an account of an event early on. This can set off a ‘false alarm’, sometimes referred to as ‘re-traumatisation’. Finding out about the trigger is a subtle process that requires the therapist to wait until you know enough about a client’s defensive response – in order to say something useful about the Amygdala at a later date!

I say this to the wider world as there may be some clients who have been puzzled by their therapist’s apparent lack of curiosity!

The fundamental rule here is that symptoms are designed for a purpose but that purpose is often obscure. However, our experience of events – located in the body – is more often less obscure.

Therefore, linking observations to body sensation can help understanding. Our cortex can make sense of sensations in our body but finding an alternative interpretation requires sensitive timing and a judgement call. If the other person is to find information about our neurology useful to them, then both the cortex and the Amygdala need to be prepared, The unintentional re-triggering of a defensive response is counter-productive.

Being able to react differently rather assumes preparedness to act differently. It takes confidence to know that my Amygdala can react differently. It’s not difficult to step out of my Window of Tolerance – work my way along the scenic route – only to catastrophise in the face of an invitation to react differently.

Such experiences can manifest in panic and that can be triggered by a number of things. Indeed, in the face of a direct threat, panic might well prove a ‘good thing’ if it helps you get out of there!

Once our inner experience, and some different reactions are just noticed, it may be possible to look for other explanations, but not before the ‘client’ account is accurately re-stated to them. Maybe we heard something wrong, and a ‘client’ needs an opportunity to tell us this. It can be insufficient to ’empathise’!

Accurate recall, like accurate empathy, needs to be affirmed before anything is put up for change. So there is plenty of reason to let a client tell their story and to feel their experience of it. Clients need to hear their own story, beliefs and explanations. That, alone, can make a difference. This requires an understanding of the triggers of incidents.

Only then might goals be identified. Goals are something just that little bit different I keep going on about. They might include external things – different forms of self-care or exploring how to react differently to a trigger.

Part of that last goal might be to understand the Amygdala just a little bit differently and this may lead into safe experiments concerned with control issues.

What is the primary AIM?

….. to remain in the presence of the trigger. In the present.

Being in the present still needs a plan; one that will stop and start, step back and go forward again through small defeats and small victories.

This may include attention to thoughts, negative thoughts and patterns of rumination. Each have the potential to trigger anxiety. Discouraging such responses is not there simply for the asking. Some fear relates to built-in fears (of new experiences) and learned fears (such as I should not stay in this house for much longer).

Connecting the not so smart, but older sibling to the smarter, and younger one

Thoughts are generated within our cortex; that smarter and younger part of our anatomy. Our reactions, our fears and anxieties arise in the not so smart, and older part. There may be some chance of fostering more control over the thinking that is a trigger. If we can do that, then some triggers may not be ‘heard’ by the Amygdala – with its central place in the not so smart and older area of the brain.

Some safe experiments

Let’s shift attention to some of the safe experiments that you might consider.

- You may find my material on rumination worth revisiting.

- Worry time: organise a fixed amount of time to be on your ‘worry channel’, and to – seek out a specific place for it. This confines some generalised worry to a time of day, to a given amount of time and place. This may give us more control over our state-dependent learning. This may sound perverse – to continue a seemingly unwanted behaviousr- BUT humans are not good at stopping things. They appear to be better at starting something else. Why not give some air space to the worry channel and free up time to do ‘something else’? This may focus our energy differently and our time can be structured differently as a result.

- Finding alternative meaning: words and thoughts have only the meaning you put on them. But what you think can activate the amygdala. Is the future really going to turn out as you are thinking? Be aware that the amygdala will often react to your thoughts as though your imaginings are happening now, not at some time in the future – near or far. Spending time focused on these thoughts can activate the amygdala to produce more anxiety and physical reactions. This is another reason to limit your time on the worry channel.

If you feel bad about something from your past, ask yourself how might other people be seeing that same event? Maybe, actually ask them. Some thoughts may need to be treated with a pinch of salt. What you think, may not be what some-one else thinks. For example, checking the door handle is something other people do not find time to do. Can other people cast light on alternative ways of behaving?

Yet thinking is not dangerous in its own right

…. and thinking can make a difference. We can ‘audit’ our thoughts, test them out and compare existing implausibilities with alternative possibilities.

Thoughts are just thoughts and yet they do not always correlate with reality!

How are you living with your ‘two siblings‘? Compassion and self-compassion may help improve how they work together. Sometimes, this might involve letting go of cherished thoughts.

Can you replace the thought connected to a worry or anxiety with another thought? Catherine put it this way: did you ever learn a foreign language? If so, you will have lost some of it, if you did not use it. How might this fact of life help make a particular thought rather like learning a foreign language? If you don’t keep thinking the thought, it becomes weaker. If you replace the thought with thinking about other things, it also becomes weaker. Just like losing the language, you can lose the preoccupation with the thought if you don’t focus on it.

This raises the question: how do I plan to generate other thoughts? The term “survival of the busiest” may help here. This psychology concept says thoughts we think on most of all are the ones that take root in our brains.

One antidote is to practice positive thinking intentionally. That’s why affirmation work is worth further consideration. A further antidote is to be less busy – more self-soothing.

One thing that helps me do this is that song: Why Worry? Try this link as a distraction, maybe?