There are no examinations that test how good we are at making and sustaining relationship. We could ask others in our lives but – as Truly of the Yard says in Last of the Summer Wine – “they could be lying”.

There is no certificate to show we’ve passed. We never pass. We simply change, and our relationships change at the same time. Sometimes, they resist those changes.

That’s tricky when therapy training establishments offer certificates without ‘evidence’ or an assessment of my abilities to make or sustain a relationship. Once I even had a potential employee decide to ‘interview’ my wife to see if this might cast some light.

You see, whatever judgment is made at the time – things seem reluctant to stay the same. As I say elsewhere, Gregory Bateson, one leader of the Systemic schools, once had something sensible to say about that: specifically: “A man walking is never in balance, but always correcting for imbalance.”

Too often we live our lives through IDEAS about our relationships, rather than within that relationship. Given the value humans place on ideas, it is easy for our thoughts about a relationship to supplant the often-mundane, day-to-day attention that is required to make and sustain that relationship.

It helps to notice the everyday changes as they happen. Some of us are better at ‘just noticing‘ – that’s one of the first safe experiments I ask my own clients to try out.

The parallel processes

One thing that may be ‘just noticed’ is the complex elements in professional consultancy. Here, I focus on one; known as ‘Parallel Process’, that is, the tendency for one relationship to make itself known in other relationships…..

“We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.” Ernest Hemingway

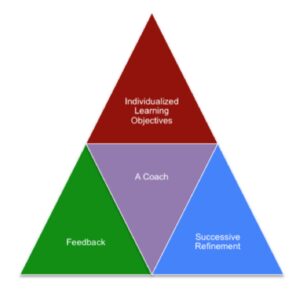

This quotation is produced in a paper by Scott Miller and others (*). along with this diagram. My apologies for any fuzzy print in both pictures.

Their Paper starts with a rather droll comment from George Lehner (1952) that psychotherapy is “an undefined technique which is applied to unspecified problems with a nonpredictable outcome. For this technique, we recommend rigorous training”.

Supervision to keep things on track

In addition, in the UK, at least, substantial supervision is required for practitioners over-seeing these processes. This supervision requires, note requires, many hours in a paid-for, working relationship with a more experienced member of the profession. That person is responsible for over-seeing the quality of the therapist’s competence.

There is limited evidence that this investment of time and money is effective – that is, demonstrating that supervision actually offers effective over-sight and advances the therapist’s learning. Sure, it make ‘common-sense’ that the therapist’s work needs over-sight; in medicine we have seen the problems that arise when the lone practitioner may be answerable to a professional body, but can – literally – get away with murder.

Miller et al set out to offer a view on how the professional development of a therapist – and the oversight of their work – might work more effectively.

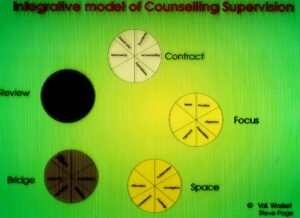

Wosket and Page: a systemic perspective on supervision

Miller’s view of professional development for therapists – as seen from a US perspective – can be integrated with a British view put forward by Val Wosket and Steve Page (there are many such models available so I am choosing the one I was trained in!):

Both illustrations emphasise the following features:

- Supervision is an organised process (even including a ‘contract’, just as therapy can).

- Effective improvement in professional performance assumes we carve out a space within which to work – in an active and dynamic relationship with some-one else.

- This process can involve clients and colleagues. This is not made explicit in either illustration so let’s say that both are relevant. The notion of ‘bridge’ between client, therapist and supervisor might apply here. and it is discussed more, here.

- In these relationships, feedback is continuous, dynamic and routine.

- These relationships, and the feedback generated, can help me to sustain an individualised approach to my progress as a therapist – still learning and developing.

….. sounds a bit like small, safe experimenting, noting consequences and living with the same?!

Parallel Process

There is a key term to keep in mind when reviewing the different relationships involved in therapy.

That term parallel process: involves noticing what is going on from one position – between therapist and client – and seeing a shadow, or echo, in what happens between therapist and supervisor.

This is a very helpful idea, as it keeps me alive to my internal processes – as they connect to my relationships with other people – some of which are professional. The labels of ‘personal and professional’ may suggest that different things go on and yet there is much overlap.

The engagement of my ‘mirror neurons’ is involved in every set of my relationships. Let’s see how this ‘conversation’ proceeds:

I have made much of the internal connections within my nervous system. In the middle of this page, I show how neurological pathways go top-down, bottom-up and side to side. The illustration, above, focuses on conversations between my brain’s right – and left-hemispheres. It’s not about one or the other; indeed, it is about each and every part of my brain getting involved.

Here’s an example of Bottom-Up processing:

…. where fingers and eyes are seen to provide ‘data’ that becomes conscious information. See how this compares with:

Up/Down, Left/Right, Side to Side: a bit at a time

….. when there is both learning bit-by-bit and learning by absorbing the whole picture. The two processes seem exclusive of one another.

In practice, of course, developing small, safe experiments requires us to live with the detail in order to absorb the larger picture. In similar fashion, it requires me to live with the ‘logical’ and the ’emotional’ at one and the same time!

For those familiar with this website, you will notice that I make much of the “non-predictable outcome“ in small, safe experiments. On that basis, George Lehner might well disapprove of my stance and recommend some better sense of order.

I argue that the “non-predictable outcome” is to be valued in therapy. This assertion makes therapy different from many other forms of enquiry. I will argue that the feedback systems used in therapy need to foster curiosity and, thereby, help the practitioner and client live with the anxiety that can arise from not-knowing.

Once we default toward the pursuit of knowing it all, then the therapist is off course and likely to ‘lose’ their connection with any client with a different sense of ‘knowing’.

By the way, I value my own clinical supervision a great deal, in case I sound sceptical about it!

(*) Scott D. Miller, Mark A. Hubble, and Daryl Chow (2018) The Question of Expertise in Psychotherapy Journal of Expertise Vol. 1(2)

Further leads to consider

Some of the models that inform therapy

….. with small victories and small defeats