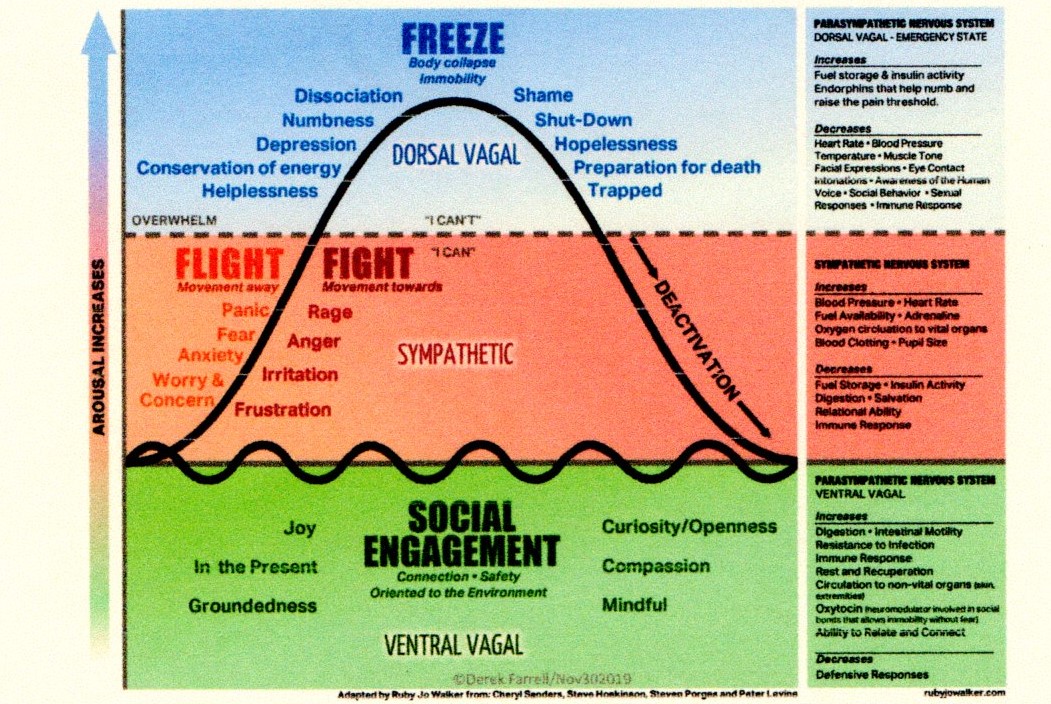

My header illustration looks forbidding. Let’s work to unpack what Flight and Fight and other defensive moves look like.

As I specialise in trauma management, I am often asked about how treatment works. The short answer is that often we do not know! The American poet, John Roedel offers one explanation that is powerful.

I comment on ‘types’ of trauma on another page.

Success in treating trauma

There are many therapists who get good results even if the schools they were trained in, and models used to explain things, offer less clear evidence of success. This seems to arise because individuals can be well informed and skilful, and other colleagues are less successful; it all evens out too readily in the end – one reason why I have written the commentary on Person-centred therapy.

Skilful therapists

I’ve mentioned a few skills already, but I will focus here on Peter Levine having revisited some of his material recently. As with Bessel van der Kolk, Peter looks at the responses of our body and he asks how we can work therapeutically with the body in different ways. If you want to research a practical and direct approach to trauma therapy, visit Babette Rothschild.

All of them, along with most body-orientated psycho-therapists, encourage us to observe our whole body – rather than anyone part of it; to respect heart, brain, gut and lungs, as John Roedel puts it.

Where to start?

The small, safe experiment of ‘just noticing‘ can help here. The Body Scan experiment is a good example of an experiment that helps with ‘just noticing‘ . Just noticing is the ability to stop, to attend and to be present in your body, now.

What are your thoughts, what are your feelings and what sensations you ‘just notice‘ at this moment.

It’s as simple and as difficult as that.

By the way, noticing can work well when something is written down about what WAS just noticed.

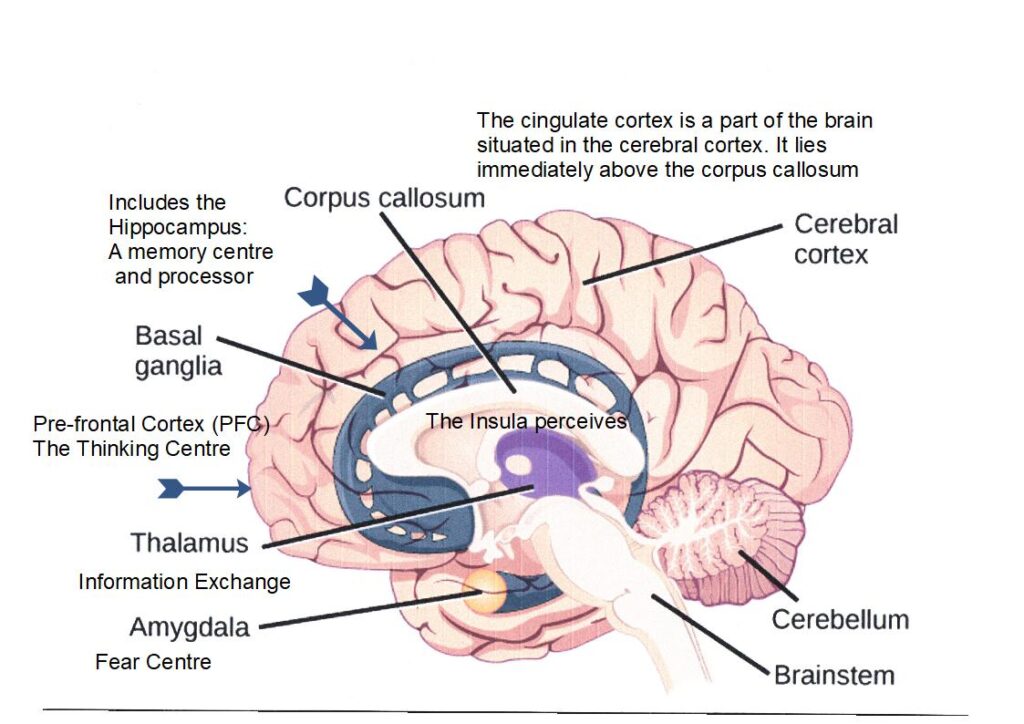

The brain responds almost instantly

The different ‘parts’ of our brain and our body work together – in an integrated fashion. It’s still helpful to know what the different parts are – and how they play a part in our overall response.

One thing you may become aware of is your own flight/fight response. The responses of the lower brain, and the amygdala in particular, as it helps us run or fight in a threatening situation. We can recover and escape, possibly without long-term physical or emotional damage.

When we cannot escape

However, if we do not run, the primitive circuits of our older and not so smart sibling can persist and take over. After an initial boost of energy and focus, our ability to function will deteriorate. The potential for post-trauma starts to be set up.

If you can’t fight or flee – you may end up frozen and helpless. This can manifest in fainting – though I would emphasise there are other reasons why we faint.

Therapy is intended to help you work through unpleasant experiences so any trauma is not ‘frozen’ in your body. Therapy can help us to find a place for the experience that makes sense – to know it as a memory yet place it at the ‘back of our mind’. It obstructs and preoccupies us when any memory is stuck at the front!

Making the implicit, explicit

In the jargon of therapy, this process is called making the implicit memories, explicit. Implicit memories can hold power over us; whereas bringing the memories out into the open can diffuse that power, and even return it to you as usable insight and wisdom.

In his writings, Peter Levine, talks about the body as a container that embodies all our experiences – everything we think and feel. Simply appreciating that we live in a body, and not in our heads, starts to give us therapeutic opportunities to build a safe environment.

Dan Siegel has a lot to say about this and you may be interested to explore his view of ‘Mind’. This is summarised at the bottom of this page.

Who tells the story about what happened?

The bodily events – happening one after another – can offer an account of what is happening. Also, it provides a sensation that can help ‘glue’ some events in our matrix memory. Also, the ‘story’ we tell rather depends on the workings of our younger and smarter sibling.

Changing that story may provide one part of our recovery but only if the way in which we once felt inside is ‘unglued’ – that is, experienced, not avoided.

Once we regard the body as a source of information, and tune in to what is happening in the body at any given moment, we may be able to release ourselves from some of the trauma held in the body.

Sometimes, we may even find it helpful to thank our bodies for looking after us in times of trouble (not that we will be thankful at the time!).

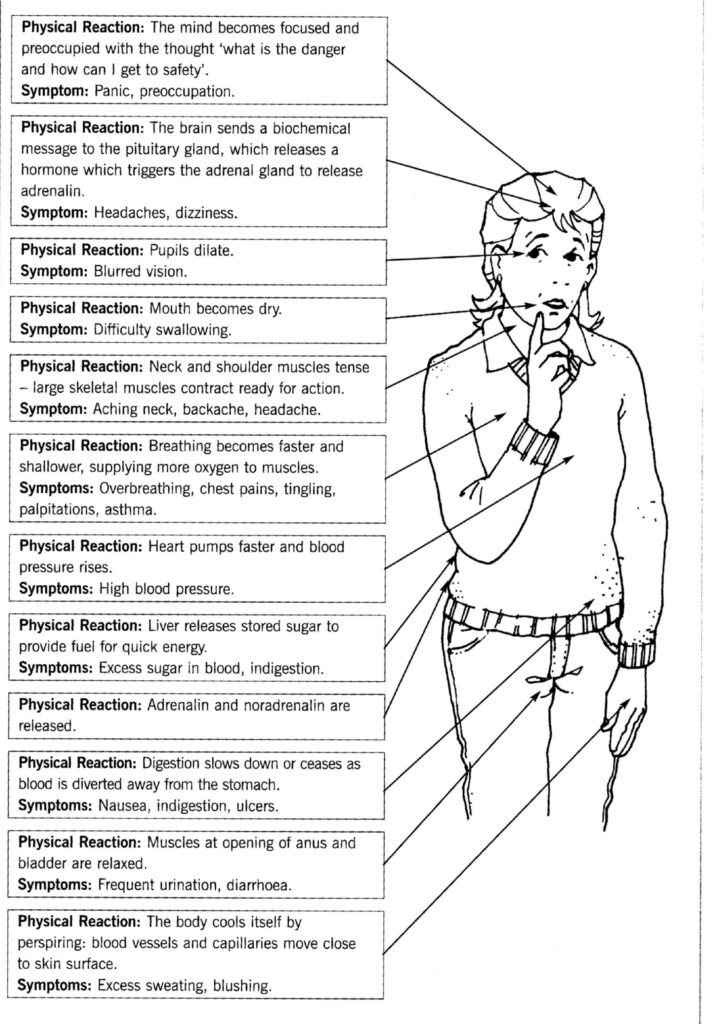

Some common body responses to high emotion

Another way to view this Flight, Fight, Freeze and Faint response is to study the rather complex illustration of the Vagus nerve. There is more on Stephen Porges’ account of the Polyvagal system. Polyvagal theory is a large and complex subject to research. It is not essential to grasp it to design and implement a small, safe experiment.

Pages on this website provide a number of relevant leads to work on. It does demonstrate how modern therapy and modern neurology appear to be coming together.

It is not a study to take on lightly! However, it may be encouraging to hear Stephen Porges speaking on YouTube.

How can we use our own neurology in practice?

When body scanning, just notice the thoughts, feelings and sensations, as described in the main body of my website. When it feels right, focus on the sensations and stay with the body experience. Start to just notice the intense sensations and feelings as moment-to-moment experiences.

Do not divert or distract yourself with starting something different. To do so would take you into a different set of experiments.

Just noticing these responses in the present can become very freeing, even if they seem to invite freezing as well. However, those feelings can transform themselves on their own – without action or the need to play them out.

Just noticing or letting it all out?

Compare this with the mid-20th century approach of Alexander Lowen and Wilhem Reich. They recommended that therapy work with feelings required discharging them in some fashion; by acting them out. Today, we are aware that we are able to stay with the feeling and not necessarily express it outwardly. Feelings can still transform; indeed, the neurology of how feelings grow and subside rather require them to transform.

This leaves the issue: when might acting out work or, indeed, leave us stuck with more to come? When is this acting out, or cartharsis, as it is known, not required for healing to take place?

Acting out

The general answer is that acting out will work in the here-and-now. When it is ‘situationally appropriate’. That is, when the threat is present and immediate. If I find myself in a circumstance that is potentially overwhelming, then it is usually better to act. That begs the question: what happens when we cannot fight or flight?

The alternative to fight or flight is to faint or freeze. In my video of the impala, he is able to recover and get away. This is not always possible for humans. The state of freeze can foster stuckness – like a bunny caught in the headlights.

Freeze works best when we need to be anaethesised or prepared for death.

Acting out, and acting in

I have worked in the area of offender management and, in particular, domestic abuse. Here I notice how angry people do act and do damage. Sometimes they will speak remorsefully afterwards, but most often, this belated apology appear non-genuine. Furthermore, they are likely not to feel their anger after the event. They have acted; their feelings are dispersed.

That action, anti-social though it may be, is defensive. Instead of just feeling the anger, it is acted on and minimal residual feelings are left on several occasions. It would be handy if some genuine shame could survive, but with some people this does not happen. In other people, the shame drives us to very different places.

So, in brief, how do you develop a sense of the body as a source of safety, rather than a repository of threat? Everything keeps changing but the body is still here; awareness is still here. We can tap into that.

The body is an important source of information

…… by tuning into what is happening in the body, and by body scanning, we can look our fear in the eye – not as our best friend, maybe, but as a powerful tutor.

An alternative view is rather better expressed by John Roedel. This is called: my brain and heart divorced.

See his story poem at: on the internet, say, at the Maggie Oliver Foundation.

Return to

Actions that might make up a nudge, or small, safe experiment

Body responses to high emotion