I have been asked about the way safe experiments fit together. My main web-site does read like a long list but there is a thread linking them all.

I was reluctant to identify that thread as it comes out just like another model, but I want to highlight one point of detail. This is important point where I depart from Dan Siegel’s view, as put across by other trainers.

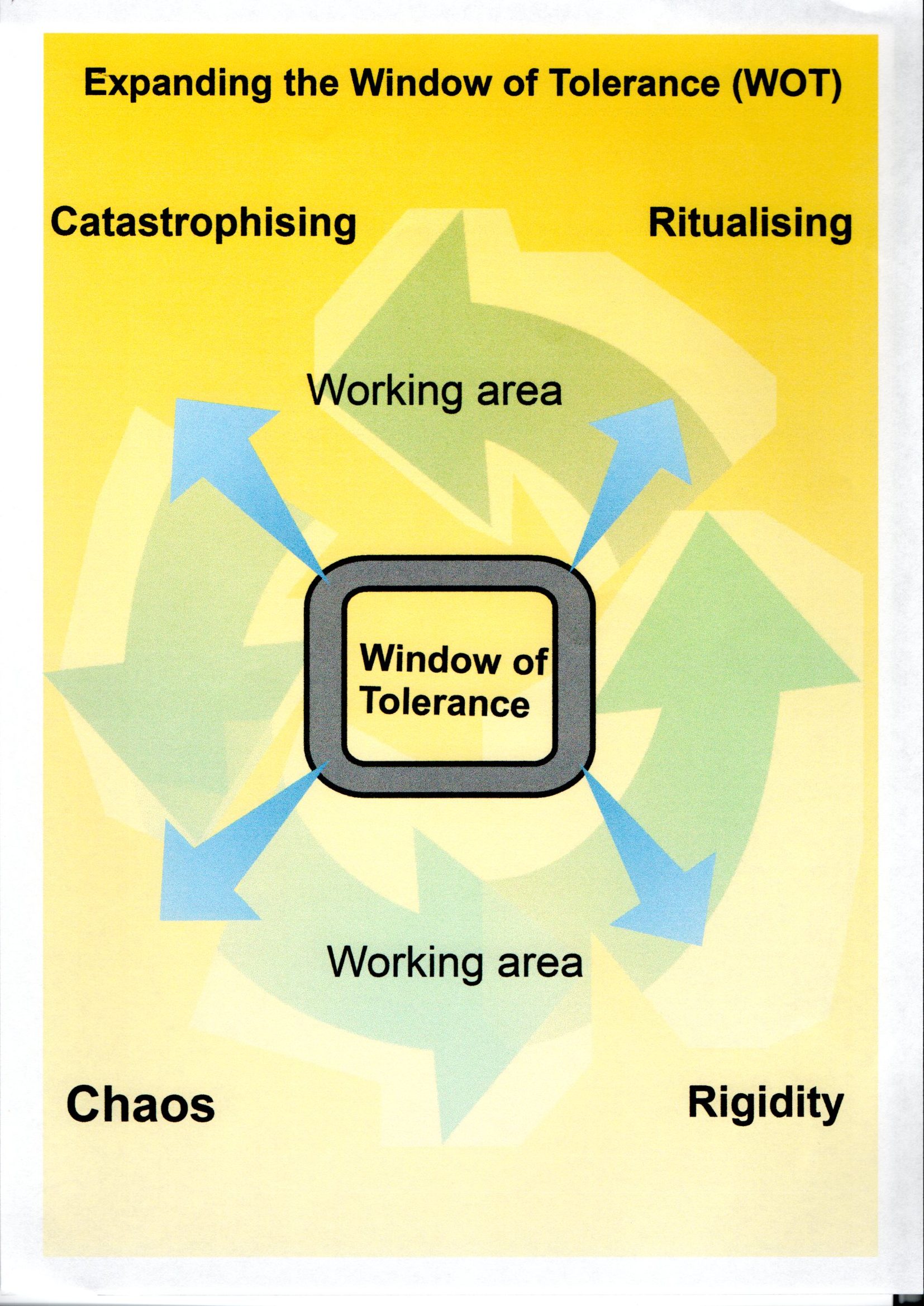

The diagram, below, implies that effective change can happen only at the edges of the Window of Tolerance. This is how one training company represents Dan’s perspective:

Note how any decisive move beyond the Window of Tolerance, takes us into hypo-arousal or hyper-arousal (my own illustration, below, identifies four examples of these states).

Stepping outside the Window of Tolerance

My diagram below, by contrast, suggests the Window of Tolerance is a valued and needed safe place, but effective change requires that we take planned and measured risks to step outside. You do not simply push from the ‘inside’.

My professional experience of what happens around the edge of the Window of Tolerance seems different from Dan’s. I say that effective change requires us to devise steps that will help us remain outside the Window of Tolerance – only to return from time to time for a rest and to contemplate on our results!

I see this point as important: it’s not just an argument about presentation. Some of us have a narrow Window of Tolerance, others have a wider Window. This website, and therapy, can help both groups of people, but each of us has to step outside to stretch our boundaries.

You can ‘push’ from inside, design an action that is important to you, but a ‘pull’ from outside is a vital part of the action as well.

Take a risk: step outside for a few moments

My diagrams point out that there are risks involved in stepping through the Window of Tolerance and going on a new journey.

It is possible to fly to one of the extremes of hyper- or hypo-arousal or, indeed, to fall into a combination of those extremes. Such extremes are STOPPERS that describe common human responses, but, in my view, those responses impede progress in therapy.

Dan’s model recognises that the extreme responses obstruct effective change but it’s my view that the ‘real’ progress is made outside the Window – by learning from the small defeats at the same time as risking an over-reaction!

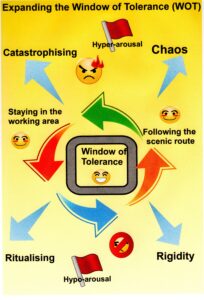

This is how I have represented the process of change. It is a modified version of the illustration that was in place, here on the website, for several years. Thanks to folk who gave me feedback on this. I can see that ‘catastrophising’ is but one example of a hyper-aroused response. Rigidity is but one example of a hypo-aroused response. I had not made this clear up until now.

Robin’s view of the Window of Tolerance

I am concerned that the illustration, below, is getting too crowded, but I expect that will change again at some future date! Want to help me with that!!

My illustration suggests that I can design safe experiments behind my Window of Tolerance. However, implementing a safe experiment requires me to act. One such action is to step outside my Window of Tolerance in order to start along my scenic route.

As I stay on the road, my safe experiments can help me to expand my Window of Tolerance (WOT). My diagram does not show this process of expansion, so can you imagine it getting bigger, as you read this!

Each time I complete a circle – represented by the red and orange arrows, in the middle – my Window has the opportunity to expand. That is not guaranteed, it’s just possible.

…. but only one small step at a time

This expansion is possible with each small step. Even so, actions bring the ever-present risk of creating stress. We are wired to be cautious about ‘too much’ stress when the going gets tough. It is only too easy to react badly and then I might jump to the extreme responses as listed at the four corners of my illustration.

I have developed a new set of illustrations to break down the process of change even more.

Adding a view from Stephen Porges

If you consider Stephen Porges’ view of the neurological responses to change, it is possible to see how taking a step too far can lead me to over-react and go into hyper-arousal. it is equally possible for me to go into hypo-arousal – when I scare myself into acting like the deer in the headlights – I stop still, or go into ritualised actions of self-defence.

These are just two of the adverse reactions I might experience. There are others possibilities described as flight, fight, freeze, faint.

Designing your own

If it helps to consider how to avoid these extreme responses, take a look at this page:

….. for an explanation for why Small is Beautiful! Who remembers Schumacher, then?!

The Window of Tolerance (WOT) is the area where we can stay and feel familiar. Familiar tends to be ‘comfortable’ but not necessarily OK. It is not an area in which change is easily obtained. Each of us has a greater or lesser willingness to expand that window in our day-by-day ‘learning’.

Any move outside the Window of Tolerance invites change and the outcome of any change created can be unpredictable – sometimes welcome (a small victory) and other times unwelcome and unintended (a small defeat). Safe experiments can help identify the STOPPERS that hold you up, and foster the ALLOWERS creating the change you want.

Managing imbalance, not keeping balanced

My diagrams emphasises that the path toward change rarely follows a straight line. Changing things in our lives is, as Gregory Bateson, one leader in the Systemic school, once said in the mid-20th century:

“A man walking is never in balance, but always correcting for imbalance.”

That correction of balance can be helped by a number of small victories in tension with small defeats.

It’s not so different from the Autonomic Nervous System, operating as it does, through stimulation of a Sympathetic system to energise us, and allowing the Parasympathetic system to slow us down and relax (excuse the simplification).

A healthy path weaves around corners and hits obstacles. Further accounts of that scenic route are described in two other pages:

It’s not so different in education

I learned much about this scenic route during my teaching career. I observed that the process of learning can be uncomfortable for adults and, at some point, it can be uncomfortable enough to motivate us to move toward another place. See more at:

The Learning Curve: taking a scenic route to change

The ever-present risk for any of us is that, under pressure, change can lead to confusion, or chaos (“I don’t know; I don’t understand“). For others, the risk is to become rigid in our problem-solving (“this is the way I’ve always done things“).

In these extremes of confusion and rigidity, change struggles to be effective. In another place, the pressure can generate anger. Now that might help but only if I can avoid striking out in frustration and blaming all and sundry for the results being generated.

It can be made worse by cycling between each of the extremes. Any safe experiment runs the risk of generating a ‘small defeat’ when we jump to one of the four extremities identified in my illustration.

I’d prefer you to have only ‘small victories’, but that’s not going to happen. Therefore, the design of any safe experiment has to accept the result might be a small defeat. You and I need to build in ways to meet such defeats.

It’s still about doing something just a little bit different

My recommendation is to ask myself, and for you to ask yourself:

“what something can be done just a little bit different next time around?”

This is a valuable question when the extreme response is our tendency to catastrophise (“I’ll never get this right, ever” and ritualising (“I’ll only get it right by doing this every time”).

Therapy provides an opportunity to move outside the window of tolerance and expand our experiences. Therapy can help to see that the process of change is safely contained. This is not guaranteed, of course, and it is easy to retreat and slip back into old, familiar ways. Such ways may be unwanted to some degree but we can prefer them simply because they are familiar!

…. and if I jump to one of the extreme responses?

So the diagram points out that our ability to change suffers when we are chaotic or rigid in our problem solving. Catastrophising and ritualising has a similar impact on our efforts.

Therapy can improve performance through small amounts of change. This emerges from small victories and small defeats – as long as we have recorded some results and can come more aware of what is going on.

I am saying, then, that a way toward better well-being is something like: “what step can I take now to do something a little bit different?”, just as stated above.

In practice, then, if this way to initiate and promote change is going to help at all, please consider some of the following challenges:

* what encourages you into chaos or rigidity, or both.

* what might ‘inoculate’ you against chaos and rigidity?

* DITTO, for catastrophising and ritualising.

* do YOU have a ‘favourite’ out of these four possibilities – chaos, rigidity, catastrophising or ritualising? Alternatively, do you mix them up?

* what can you do to widen your Window of Tolerance (WOT) by some small step.

* what can you do NOW?

Some training courses that might interest you

For more information take a look at this material made available on YouTube by a US training group, The National Institute for Clinical Applications in Behavioral Medicine (NICABM). It includes material from Bessel van der Kolk where he talks about his use of various breathing-related exercises. This site is well worth a visit, and a further follow-up.

A search for Dan Siegel’s material, say, his Wheel of Awareness, might be useful line for further research.

The Body Psychotherapists have much to offer and here you can explore the work of Peter Levine, Pat Ogden and Babette Rothschild, to name just three practitioners.

Further leads