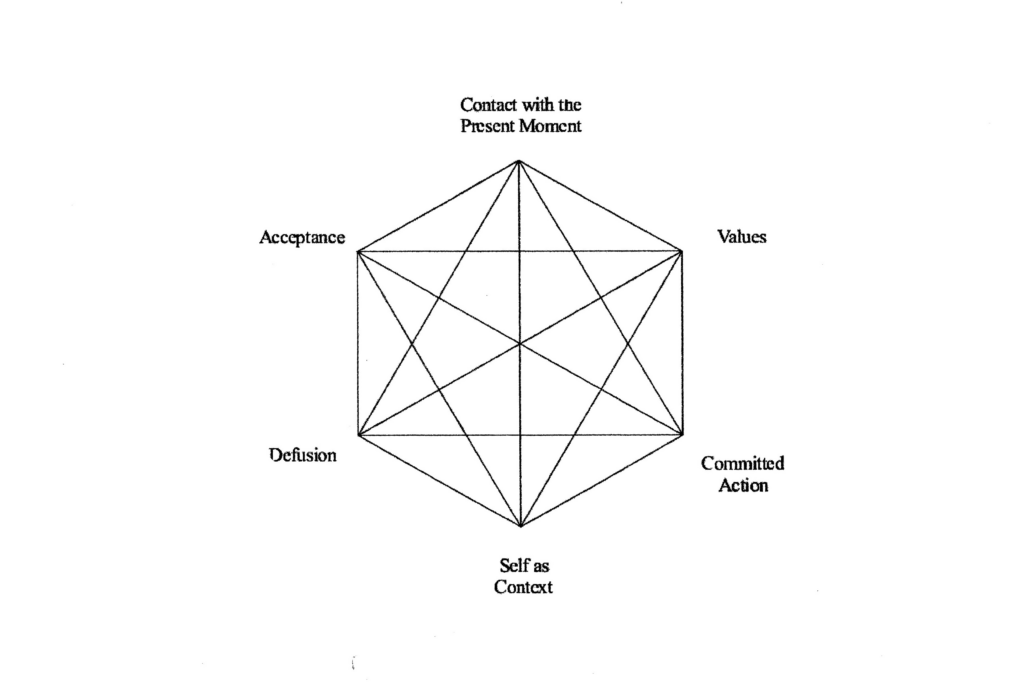

I have been asked about this approach to therapy. Elsewhere on this website, I have expressed a liking for its ‘attitude’ to people, and events, as exemplified in the illustration, above.

Now I will take a closer, more critical look at the detailed messages in ACT.

It seems a relatively new arrival in the therapy world, being developed in the mid-80’s by Steve Hayes. It has become one of the so-called ‘third wave’ therapies, such as Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) and Mindfulness-based practises.

ACT does contain elements that help readers design experiments for themselves. See –

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acceptance_and_commitment_therapy

…. for some insight into the model.

Elements of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

In general, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) encourages you to accept what is out of your control, and asks you to improve your life through specific actions. It is an approach intending to maximise your potential. It’s practical about ways in which to realise both aspirations.

Here is a diagram summarising the elements in the ACT approach:

I’ll explain my view a bit more, as follows:

Contact with the present moment

… relates to the Mindfulness perspective on this page – as well as other body psycho-therapies. Explore, if it helps, the work of Peter Levine and Pat Ogden. There are many others, but two will have to be enough here!

Acceptance

…. is related to the ability to decide between what you can be change and what IS. ACT has useful things to say about our thought processes and how they can be harnessed to revise our behaviour. I refer to this further using the words of Rudyard Kipling.

Values

The model seeks to make explicit values we possess and the ways in which our values help or hinder change. I make my own ‘values’ statement on such pages as:

Responsibility for safe experiments: https://your-nudge.com/can-i-use-safe-experiments-to-help-others/

Defusion

…. is a specific technique rather similar to the experiment of “Just Noticing” or “Stepping Back”, included on this website.

Defusion assumes we can become over-focused on some aspect of our behaviour, particularly the language we use, and this restricts our ability to change that behaviour. For instance, in our language, it is often the case that we blame others, or blame ourselves, for things that go wrong.

Both extremes of this Locus of Control (LOC), as it is called, are unlikely to throw much light on the ‘truth’, whatever that is. Defusion and stepping back can help us look at the large picture and notice better our own tendency to over-focus.

Committed Action

…. for me, this is ACT at its best as it is being very clear about doing something differently and noticing the outcome of your actions and being prepared to change once those outcomes become clear.

Self, as context

This element of the model is interesting. It places you and me at the centre of the process of change and respects our ability to notice and sustain changes we make. However, as with the Values element, I am left uneasy about how this element works in actual practice.

Symptom reduction is not the goal of therapy

This is based on the view that the ongoing attempt to get rid of ‘symptoms’ actually creates a clinical disorder in the first place. Personally, I take the view that symptom reduction could be a good start, if it improves my confidence in doing small, safe experiments.

The ACT model seems to help us to clarify what is important; it does inspire you to experiment. ACT helps by being action-oriented; it encourages you to find your own ways to change. Change is achieved through teaching skills gleaned from, amongst others, the cognitive behavioural approach (CBT) and Mindfulness.

It is the ACT view that skills need to be taught that starts me asking questions. What are those skills, and who defines them?

My overview of the ACT model

ACT has now joined the ranks of those models that initiate training programmes that slide down the slippery slope towards ‘this-is-the-way-to-do-it’.

I want to avoid detailed specification in the design of safe experiments, but you will still find exceptions to that rule throughout the website. You do not have to follow the directions I offer by this over-supply of possibilities.

I hope I make it clear who implements the experiment (you) – and who has to respond to the results generated (you, again). It is not me, unless I am designing something for myself!

There is an implicit assumption in the ACT model that it can define ‘safe experiments’, and it places emphasis on having a guide to help you avoid a small defeat. I dispute the inference that defeats are to be avoided. They are necessary to our learning, and I encourage you to look out for them.

Therefore, the ACT view of Committed Action is both welcome and troubling.

- Welcome in its asking for attention to ‘action’.

- Troubling – given its respect for education of the self, when offering to ‘train’ others toward an ACT notion of personal growth. My experience is that few training programmes are focused on an individual learning about themselves, for themselves and assessed by themselves.

OK, it’s hard work doing that, but I see no shortcut to offer.

So, at this point, I become cautious, and I find ACT offers a number of strategies already around in existing areas of psychology. For instance, Acceptance is a form of ‘just noticing’, as touched on in this website.

Mindfulness, like Yoga, is one approach to experimenting that may help you, but you will not know that until you try it out. Also, it is a very large subject. You can go to Bangor University and do a post-graduate programme in Mindfulness practice!

A specific reservation about ACT

I say ACT shares with most models a lack of candour about you finding out what works for you. It makes ‘mention’ but in the same tradition of the person-centred school, it seems to say progress can be made only if you build your approach around an ACT perspective. For instance, consider this view from Dr_Russ_Harris in a PDF entitled A Non-technical Overview of ACT:

“ACT assumes that the psychological processes of a normal human mind are often destructive, and create psychological suffering for us all, sooner or later.“

This passing assertion fails to respect both the possibility of learning from symptom reduction, and the value of learning from small defeats. Where is the evidence for symptom reduction worsening our progress on the ‘scenic route‘?

The quotation sets up an almost neo-Freudian way of thinking: that effective therapy is full of unintended consequences that only a fully-trained expert can help you avoid. I repeat, there is little respect for learning from small defeats. This creates a ‘Project Fear’ that warns you off doing it yourself, lest you get it wrong.

The best you can do, he seems to say, is to accept the hurt that comes with getting it wrong. A real giveaway from Dr Russ Harris is the sentiment that: “ACT allows the therapist to create and individualise their own mindfulness techniques, or even to co-create them with clients.” Note the way in which the role of therapist and client are defined. They can EVEN co-create techniques!! What about ‘clients’ creating something for themselves? They might, just might, be willing to share the experience in a therapy session?

My own website says: you go your own way and take the consequences of so doing.

I suggest you will progress on a scenic route where your defeats are at least as important as your small victories.