Change created by separation, death or illness can come suddenly. Without knowing the queen, in person, millions of people experienced the shock of her death on the 8th September 2022, aged 96 years.

Although the event was not so sudden, given her age and illness, such losses – particularly those in our own families – undermine our sense of ‘normal’ and being in control of our lives. I felt this when Kennedy was assassinated and some of that experience remains with me sixty years on.

Loss of employment or move of home can both qualify as sudden change. Even the arrival of a new child into the family, or marriage, itself, can produce unexpected changes. Not all outcomes of large changes are welcome, e.g. disrupted sleep and a forced adjustment to our ‘normal’ routines.

Facing the death of some-one important to us is the most obvious sudden change that is ‘forced’ on us. Our bodies come and go. Because no-one is exempt from death and much research has been devoted to the subject for that reason.

The process of loss in the face on forced change

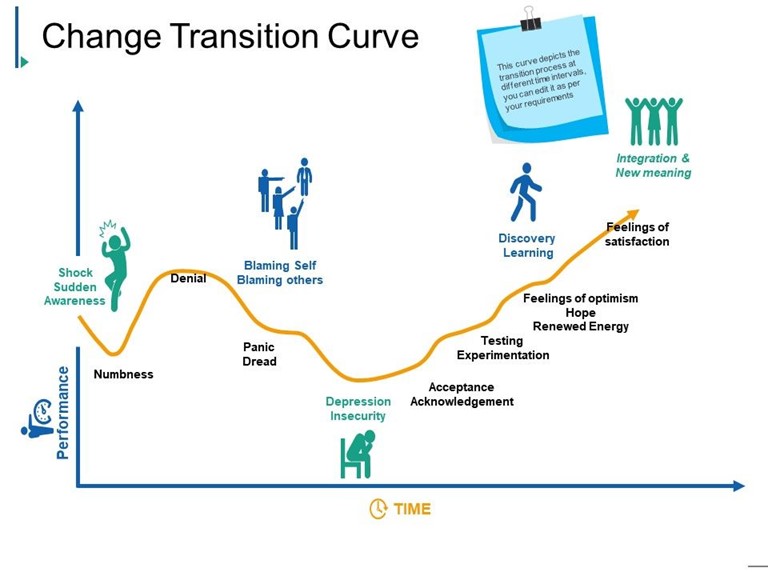

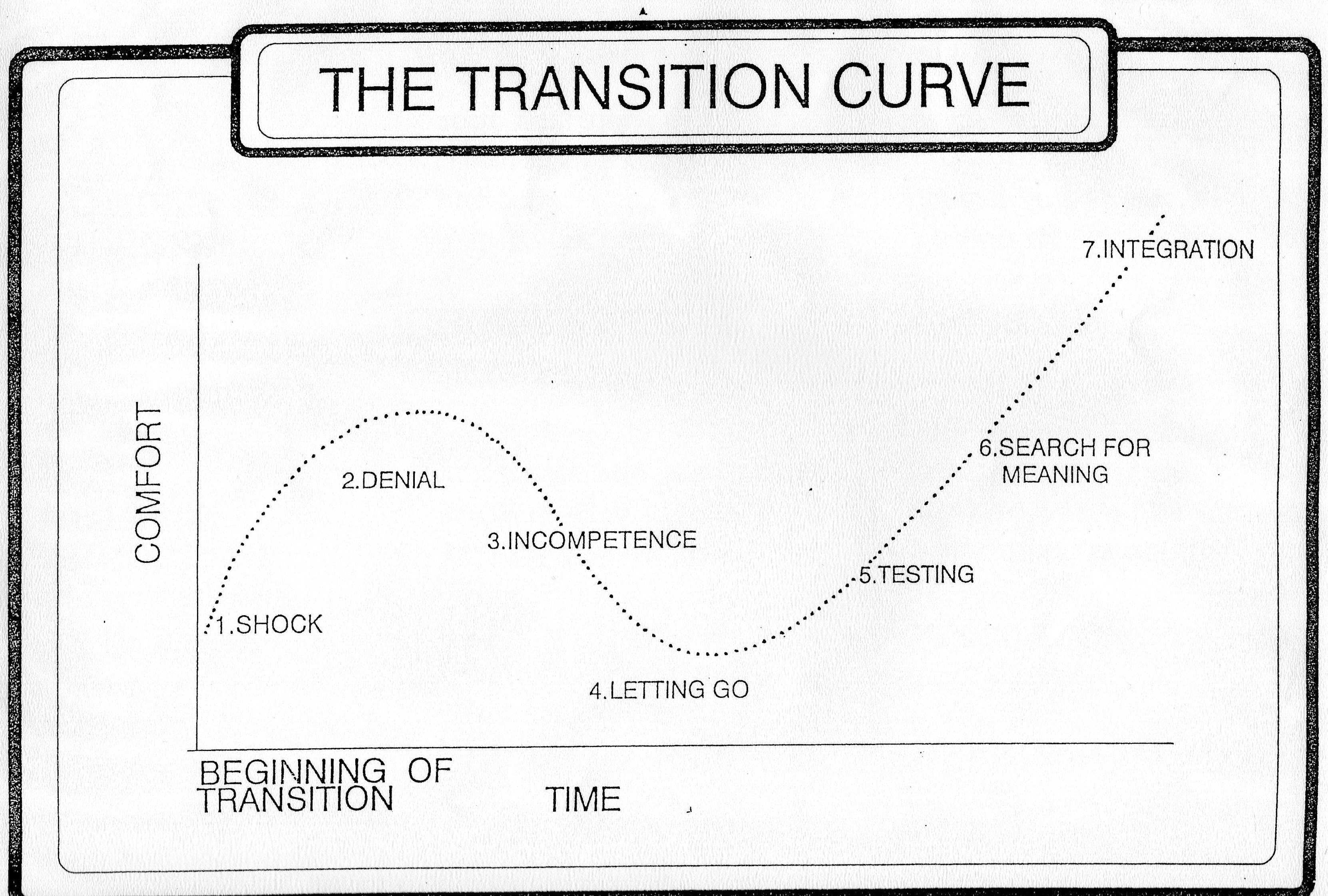

Research on the processes of loss has been helpful in telling us about the processes of change. Below are some versions of the change process likely to follow after a shock or major life change. There are others on this page.

Research and practice seems to conclude that we are not all guaranteed to work through our changes, as listed. It is possible to skip a ‘stage’ and some people find they move back and forth between stages.

Do not think of this diagram as offering a straight line towards change as nothing is inevitable.

That said, the process appears to arise from our ‘hard-wiring’, an internal neural activity that is ‘universal’ to human beings. Therefore, few of us, regardless of culture or nationality, are immune from the process. We will manifest it in many ways and, indeed, there will be a number of us who will defy the pathway.

There a lot of illustrations of the change process

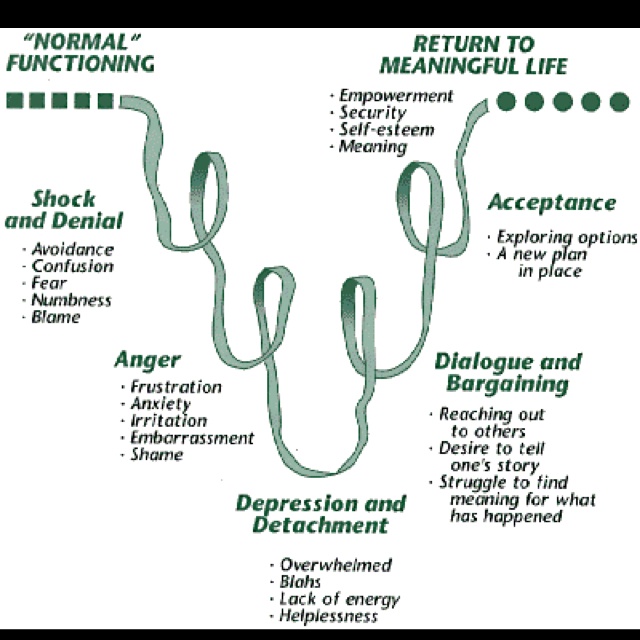

Another, rather more accurate presentation of my reactions to major change, can be found in this helpful variation to the Kubler-Ross model of change. It is more accurate as it avoids the ‘straight line’ model, and show how we humans loop and wobble through sudden changes that unsettles us. Even then, we move from an old normal to a new normal.

Change rarely follows a straight line

Our initial reaction to a major change is release of adrenaline; the body’s signal to arms. Initially, this alerts our body to pay attention and it can improve concentration for a time. Some of that energy can go into denying that anything has happened at all!

Adrenaline works most effectively in short bursts

….and works against us when there is prolonged release of adrenaline.

The experience of being flooded by such neuro-transmitters tends to lead to feeling pulled down. It make us tired and less able to keep our attention – we become less able to manage daily tasks. Over time, often slower than we might think, our bodies let go of that adrenaline overdose. We turn our energies to testing out the ‘new normal’ that has entered into our lives.

If all goes well, we find a ‘new normal’ that ‘explains’ our new position in the world. We begin to tell a revised story but that does not mean we forget the old one.

This may be a familiar process to many. It helps us think about changes we have made in our lives, and remind us that there is more to come. Most of all, however, it reinforces the adage that “time is the great healer“; there is a time to act, a time to wait and a time to reflect.

Therefore, despite what I have said to date: now may not always be a time for experimenting and creating change and uncertainty in our lives. I hope I never promised you any consistency in writing up this web site!

Apparent ‘small defeats’ can still help me change

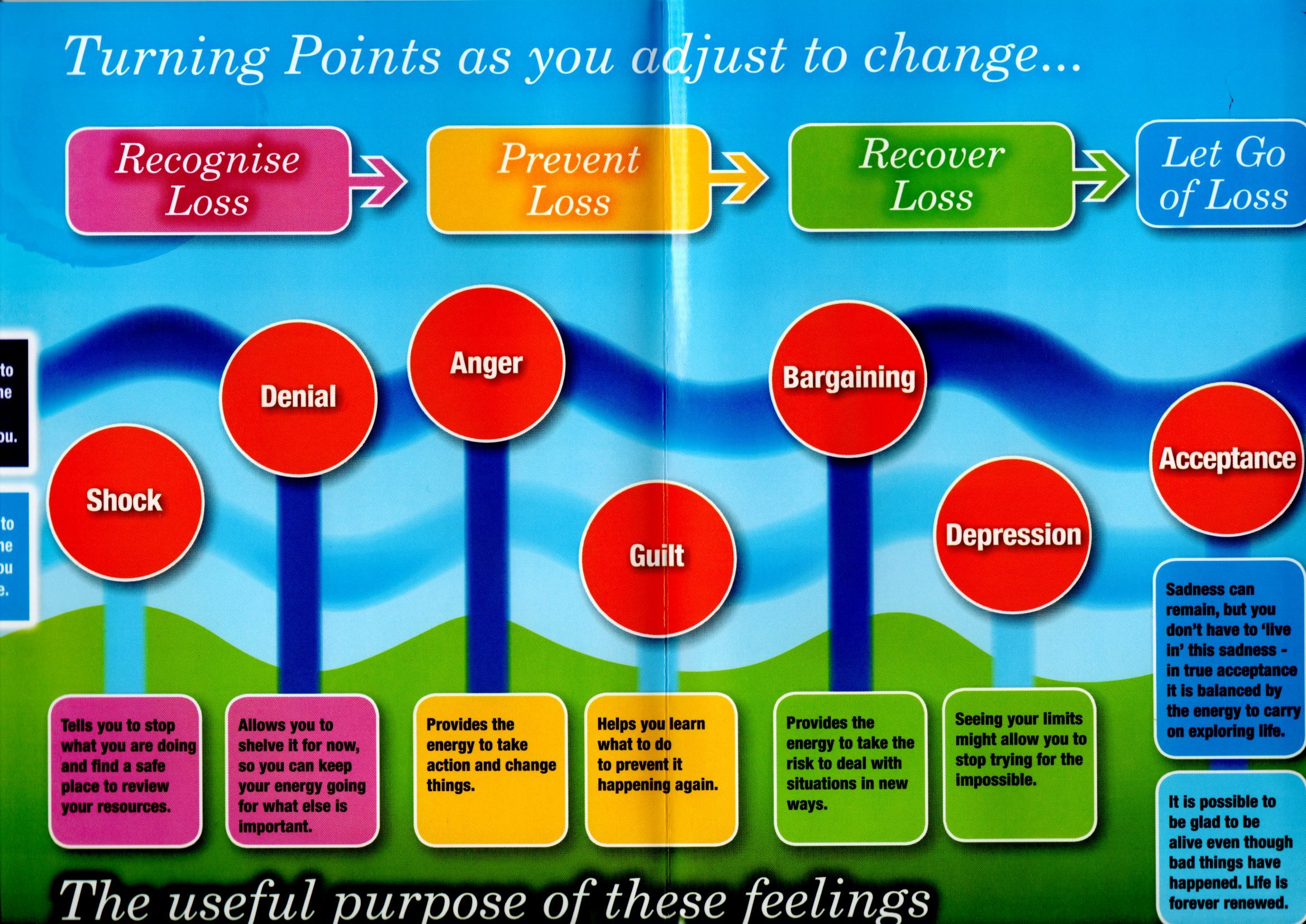

Here, below, I add a different ‘take’ on this change process. It is an illustration offering some positive reasons for uncomfortable experiences created by change.

There are useful purposes for the feelings we experience?!

I owe this very insightful illustration to Trevor Griffiths and Nightingale Conant who published an Home Study Programme called Emotional Logic. My apologies for the loss of data arising from the oversized original.

Here is my own, more detailed explanation:

TOP PINK (far left) says the ‘start’ of change helps us to RECOGNISE LOSS. The OK side of this reaction is to stop us in our tracks in order to provide the time needed to take it all in.

TOP YELLOW (middle) says one of our first reactions is TO PREVENT FURTHER LOSS. Plainly, this is not always possible, but, say, in a house move it can lead us to get ‘cold feet’. Then we need something to energise us and get things going again.

TOP GREEN (middle) says RECOVERY FROM LOSS is something we aspire to but we still need energy to make it so. We need time to contemplate and to prepare ourselves. Also, the OK side of ‘depression’ – slowing us down from action – is that it gives time to discover or develop new boundaries – so other things can be achieved…….. SLOWLY. Behind a safe boundary, we can find the time we need to make it so. I do recognise that this contemplation can present its own problems.

TOP BLUE (far right) say we are able, in due time, to LET GO OF LOSS through acceptance. I should say that this suggestion has been challenged by more modern writers. A more modern perspective is that we can absorb our losses bit-by-bit and rewrite our narrative or Script.

Below you will read about Stroebe and her colleagues. She says that humans appear to go through states of accepting change and fighting that acceptance.

This seems elegant to me. It’s similar to the way our Earth responds to earthquakes: there is an initial strong reaction as the tectonic plates shift, and there are after-shocks for an indeterminate period of time before the rocks beneath our feet settle down.

AN EXPERIMENT

As you reflect on both these charts, can you reflect on a MINOR change in your life. Be wary of exploring very disruptive changes.

Can you notice how you moved back and forth between the ‘stages’ as summarised? What helped and hindered you going on that ‘scenic route’ to a ‘new normal’?

Make brief notes on the process you used to adapt to changed circumstances. That might include feeling ‘stuck’ and unable to adapt. In that situation, it is wise to consult a therapist and get some independent support.

ANOTHER VIEW OF CHANGE

Margaret Stroebe broke with mainstream researchers such as John Bowlby and Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in her understanding of the grief process.

Bowlby reasoned that attachment behaviour had survival value for many species. The grief response was regarded as a distressing aspect of a lost attachment – a general response to separation.

This view was central to the construct of ‘grief work’ in the 20th century; a process of confronting the reality of a loss through death, revisiting the experience of that loss and events associated with it, prior to working towards detachment and change.

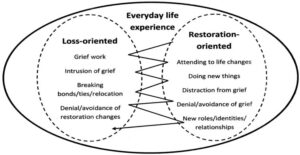

Stroebe and Schut, by contrast, developed a trans-cultural perspective paying attention to the use of language. The Dual Process model, as it is termed, sees grief as, primarily, an emotional reaction to the death of a loved one but it does not have to have detrimental consequences. Mourning was a social expression of grief shaped by the practices of the host culture. There are visible signs of grief such as crying, but there are still cultural differences.

In the Western world is it usual to view depression as a psychological process associated with bereavement. Stroebe and Schut were more concerned to emphasise that the different phases of grieving do not exist universally. Their model sees change as an active process in a changing world. The grieving process is likened to an intricately-balanced, dynamic battle that requires expenditure of large amounts of energy and re-adjustment on a number of levels.

In practice, Stroebe and Schut take aspects of the traditional phase model and introduce a dynamic component into the change process. This is achieved by formulating a set of tensions between loss of the old normal and restoration of a manageable new normal.

It conceives of people coping with two different types of stress – facing the experience of loss and just noticing our ability to restore some order to our lives. Each person will respond to this tension in their own way and in varying proportions according to individual and cultural expectations and variations.

The model infers that concentration on the aspects of our loss, and the opportunity for adjustment, can be exhausting. It imposes substantial changes on our life-style. The shock of bereavement makes the shift rather dramatic and unpredictable in some settings, and carefully controlled. Cultural and family norms will be powerful determinants of the tendency to approach or avoid one or other response.

Stroebe and Schut saw everyday experience leading the individual through an appraisal process in to cope with change in their life through an active review and rewriting of our ‘story’.

Such an approach emphasises a search for meaning; an appraisal of events and one’s own coping strategies. The individual, the family and the larger society to find a different place for lost opportunities and deceased people.

So here is a useful illustration of that Dual Process Model of Coping with Loss (DPM):

Source: M. Stroebe and H Schut The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description in Death Studies Apr-May 1999;23(3):197-224.

….. where the concept of oscillation is central to their thinking. According to Stroebe and Schut, healthy grieving means engaging in a dynamic process of oscillating between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented coping. A griever will oscillate between confronting the loss and avoiding the loss.

Note the radical difference from the older, traditional ‘stage’ models of Kubler-Ross and others. Instead of a seemingly orderly journey from loss to recovery, Stroebe and Schut say there is disorder, unpredictable disorder, in the scenic route from suffering a loss, and finding a different place for that loss some time later.

I believe this disorderliness is in keeping with models of change, including my own metaphor of the ‘scenic route’.

…. as this route includes some danger signs and rocks on the road. Take a look at this page.

SOME OTHER EXPERIMENTS

At this point, you may want to say I have no obvious losses in my life at this time. I do not feel loss or grief at this time. If this is so, consider the issue of ‘loss of meaning‘. This can arise at any time when our view of the world is shaken. A relationship may not end, but it feels under threat. Some-one says something I do not like. How do I react to that? The ‘loss’ can be quite subtle. For an example, visit this page and do the body scan.

How do you respond to my statement relating to an unjust and unequal world?

When under the pressure from conflicts, often described as ‘dissonance’ by therapists, it can help to be ‘kind’ to yourself with different experiments; especially those that allow you to “just notice” what is going on for you, now. Anything that fosters our ability to reflect can be helpful so controlled breathing can fit the bill.

Affirmation work helps here. Affirmations are short, positive statements we can hear in our heads, or even say out loud. I am including a small sample on another page along with further discussion about this form of safe experiment.

Also, you can use the body scan experiment to observe and record the thoughts, feelings and sensations that are associated with any affirmation.

In general, it is better to start with a memory of a loss of ‘things’; I’ve used car keys as an example before now. If you are going to do more, consider the value of:

Special Time which assumes there is some-one you know and trust well enough. some-one to whom you can express yourself clearly. In my experience, practising speaking for yourself – in the first person (I), and for the immediate present – can be illuminating at any time.

Any safe experiments around ‘crisis’ can help. Most losses create crises.

As you complete this experiment around a memory, consider where you might be on the various scenic routes I have described here. Notice how and when you felt stuck and unable to move on further. Reflect on what was happening at that time and, if things shifted for you, in due course.