Polyvagal theory helps us to understand how the brain connects to various parts of our body through the Vagus Nerve. It accounts for some specific responses to the workings of our autonomic nervous system (ANS).

The Vagus nerve is the tenth of twelve nerves running out of, and into, our brain.

Stephen Porges: neurology helping therapy

Why is Porges’ work so important? After all, the ‘flight/fight‘ response has been around for eons. Much was known about how it worked; how it was triggered and led us to recovery (if all went well).

What Porges identified, however, was that the simple model of autonomic nervous system (ANS) overlooked some important features. The ANS plainly played a central role in initiating and sustaining the flight/fight response. It seemed as though the ANS used a ‘pumping’ action – between our ‘sympathetic’, stirring us up, and ‘para-sympathetic’ systems, settling us down, and this kept us in balance.

Acknowledging this in the mid-20th century, Gregory Bateson said change meant “A man walking is never in balance, but always correcting for imbalance.”

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) gets complicated

My understanding is that Porges complicated our understanding of the ‘pumping’ action of the ANS by identifying the workings of the Vagus nerve. He demonstrated that it was more than a single conduit.

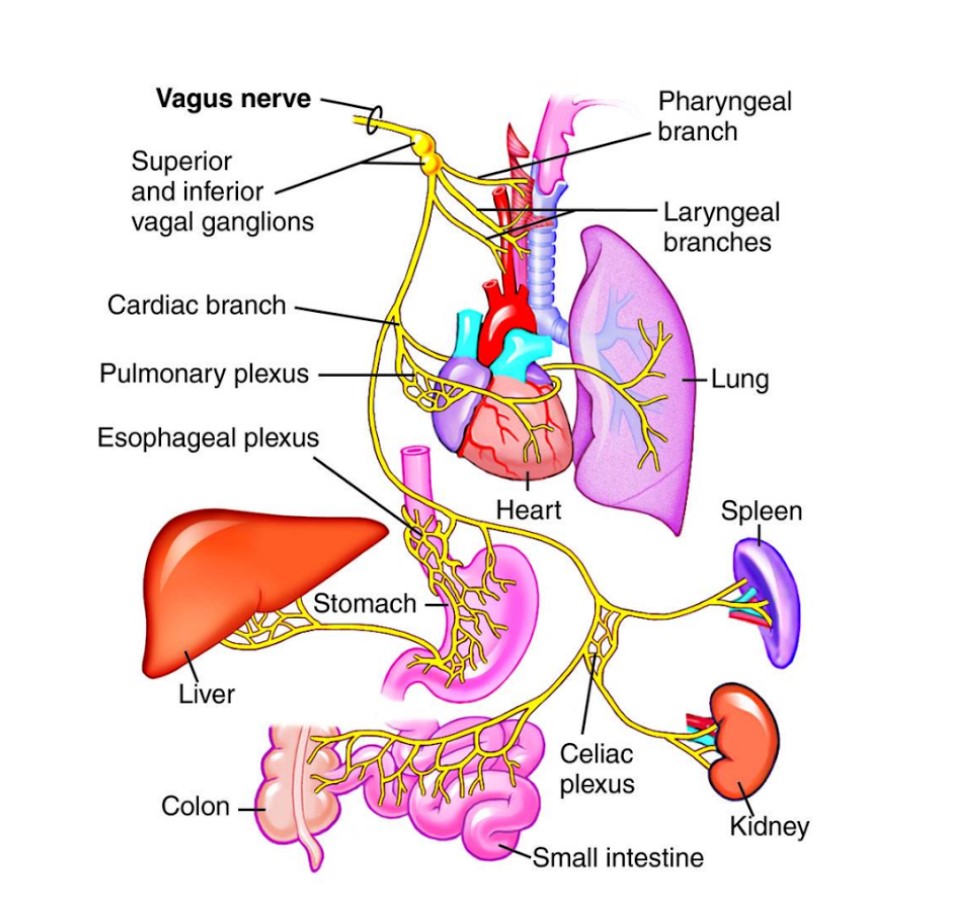

As in the diagram, above, this nerve – running the length of our upper body, comprised several off-shoots to face, upper body and ‘gut’, amongst others, Hence the label, ‘Polyvagal‘, for those many offshoots of the Vagus nerve.

More to the point, he concluded that its ‘parts’ emerged at different times in our evolution. Porges was talking about many millions of years evolution. During that time, the reptilian inheritance was altered so mammals, late arrivals on the scene, could be ‘immobilised without fear‘ without risking fatally low rates of ingestion of oxygen.

Managing fear

That state of affairs – being immobilized without fear – works differently in mammals. This is especially true in humans who take many years to become independent. Being without fear rather assumes that an infant has a safe place. For this to happen, an infant needs a caretaker who can be trusted (we are very vulnerable, and much at risk when immobilized).

Only through this process can a human learn to create their own safe place for themselves, and their own off-spring. This process is called attachment and bonding.

The Vagus Nerve evolved over millions of years

The later evolution of the Vagus nerve played a large part in helping mammals, including human beings, to detect situations in which they were safe. This process was helped by the evolution of the ventral Vagus nerve or ‘social engagement system‘ as Porges labels it. This helps humans find out who they could do business with.

BUT IT IS NOT IMPOSSIBLE to get beyond any struggle. Indeed, notions of ‘neuro-plasticity‘ suggest that it is feasible to adapt and redesign our neural pathways.

This website contains a number of safe experiments that might help those changes.

Lines of enquiry

Fight, Flight, Freeze or Faint