So says Bessel van der Kolk in his important text of the same name. My diagram, above, shows how solid matter, such as our planet, can shape space. In its turn, that space directs the movement of our planet. Something similar goes on with us human beings. We shape our communities and yet we are directed by them – often in subtle ways.

Elsewhere, you will find leads to the way SPACE, TIME AND SPIRIT can impact on our development in so many different ways. For the present, I want to move on to ‘Body’.

There is information about the inner workings of your body that you may want to explore. Sometimes you may not realise you possess some control over your bodily reactions, e.g. when you feel agitated. Other times you may fight to gain some control, e.g. when you eat or drink too much. Then it can be too late and the body takes over – as well we notice the following morning!

It is vital that we sort out what is achievable

Although I have worked in medical education on several occasions, I am no medic so I will attend to what a body does rather than focus on the actual bits and pieces.

My starting point is that the body reacts with good intentions most of the time, but there will be times when that is not obvious to the casual user.

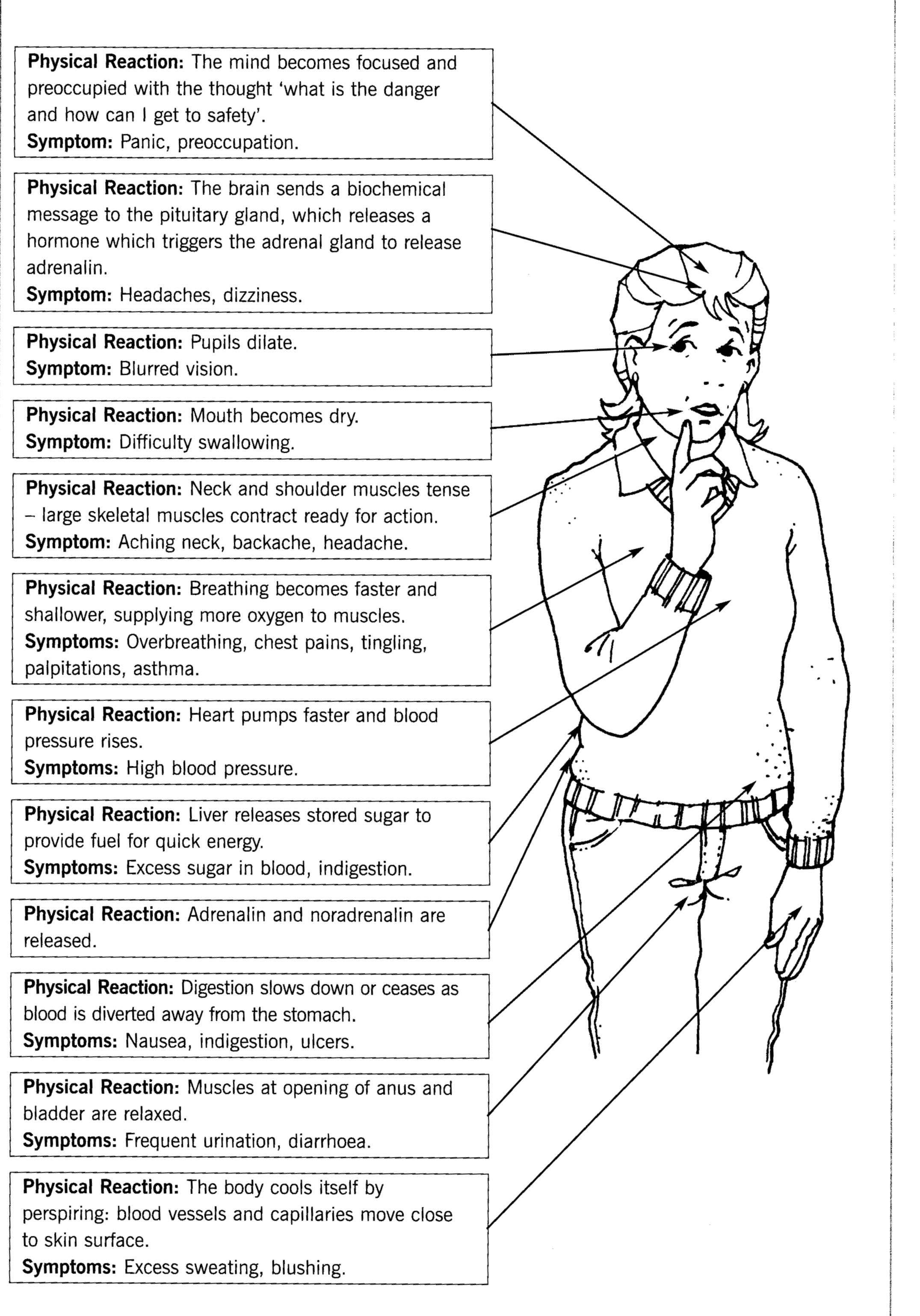

Consider the diagram below. This lists our usual reactions to immediate stress. Your body will experience some, if not all, of these symptoms if you are involved in a near-accident in a car, in a street fight or if some-one creeps up behind you.

An Experiment with Just Noticing

One safe experiment is to note which one of the reactions, listed below, make sense to you. Recall a time, place and an incident when some of these bodily reactions were in the forefront of your experiences.

What can be learned from these reactions of our body? Do we have to simply take it as part of our make-up and there is nothing we can about it; or, are there safe experiments we can initiate to make a small difference?

The most basic safe experiment that is ‘do-able’ is to measure the degree of reaction you are getting from your body. For example, if you are angry, how angry are you? If you have a tight chest, how tight is it? If you are in pain, just how much pain do you experience?

‘Measuring’ what is do-able

The subject of measurement brings me to the Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD). The key point is that the SUD is a subjective measure. You do not have to explain it, or provide evidence for your rating. Simply select a figure between 1 (the smallest amount of ‘experience’ you can notice) to 10 (where your recall of the experience is at its very worst). Be clear, here, that this safe experiment simply provides a ‘base’ line to do more experiments in order to notice if the experience goes up (from, say, 5 to 7) or down (from say, 6 to 3).

When you are gathering information about any safe experiment, it helps to notice how our experiences go up, down or stay the same. It is not possible to note what helps that experience go up and down without a SUD to monitor how it moves and changes.

ANOTHER SAFE EXPERIMENT: from Just Noticing to Body Scanning

There is an example of the use of the SUD that focuses on our experience of anxiety. Recall the last time you felt anxious. As with all safe experiments, start with something that minor. registering a SUD of not more than 6. Can you recall what was happening that sent the SUD up and/or brought it down? You may find this difficult as the changes are often created by small happenings.

If this is so, then shift the experiment to now. Do a Body Scan. Attend to the feelings or sensations in your body, now. However fleeting the feeling or sensation might be, label it and give it a SUD (“I am excited, on a SUD of 3”). Then use controlled breathing to focus even more on your current experience. Are you able to decrease the sensation of “anxiety” by a point or two, or even one-half point? It may be that the experience stays the same (at a ‘3’) so continue the controlled breathing and body scanning to test out your ability to make a change.

Bear in mind that this may not happen; the result is a ‘small defeat’ and that is all it is. It is an obstacle on your scenic route.

Keep in mind, that safe experiments can help you discriminate between what is ‘do-able’ and less do-able. So let’s go back to the range of experiences our bodies are able to generate.

For example, when adrenaline flows in your body, some threat is being considered. Some threats are immediate, present and concrete and others are potential threats.

Types of ‘threats’

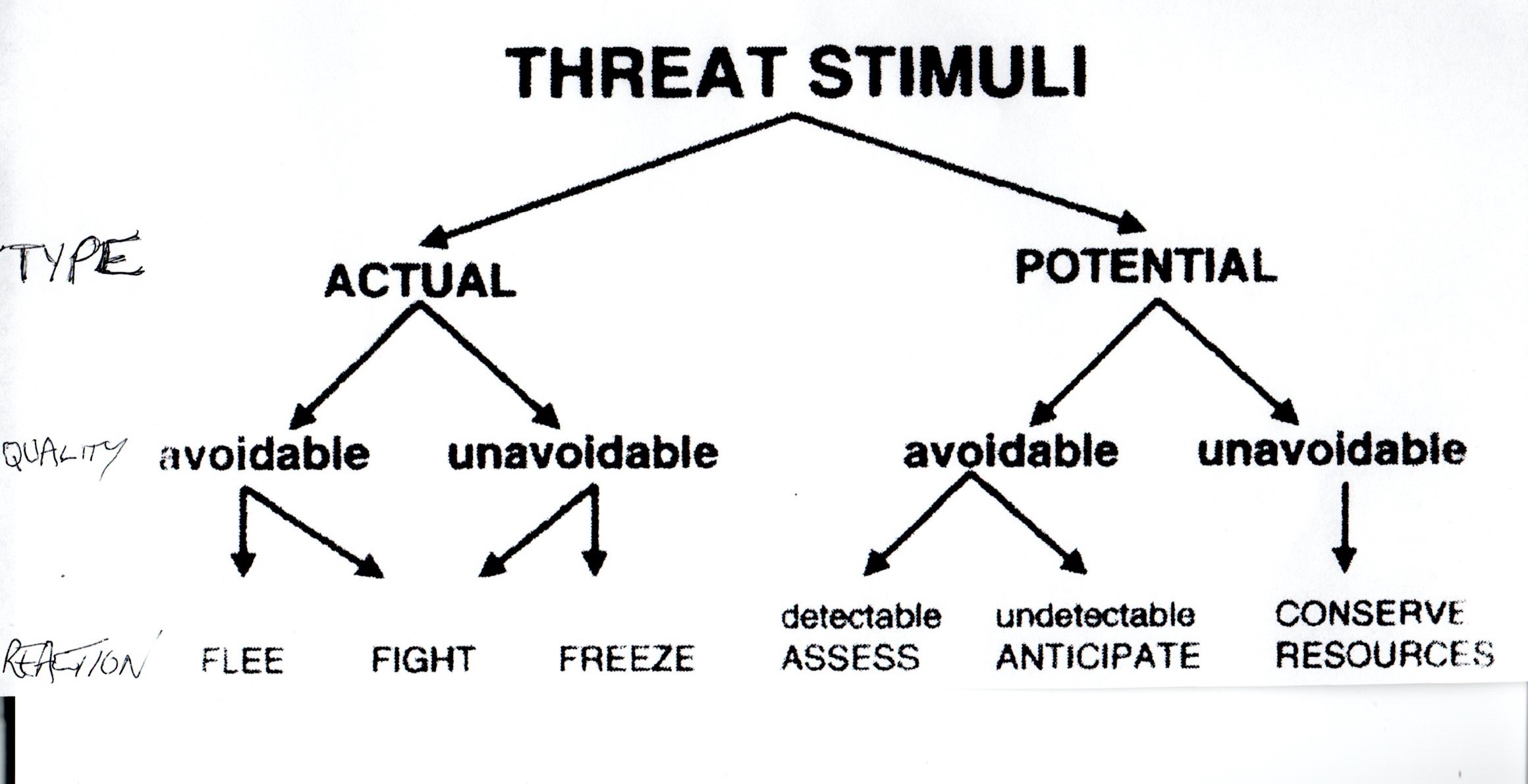

Apologies for the rough hand-written notes on the left-hand side – particularly as the added headings are important! Also, bear in mind that Stephen Porges‘ work says there is a fourth ‘F’ in the bottom left list, Faint. There’s at least a fifth one, but this is not relevant here.

Apologies for the rough hand-written notes on the left-hand side – particularly as the added headings are important! Also, bear in mind that Stephen Porges‘ work says there is a fourth ‘F’ in the bottom left list, Faint. There’s at least a fifth one, but this is not relevant here.

The diagram offers a link between different threats and what we can do about them.

Some threats are actual (a mugger is threatening you in an alley now) or potential (a mugger may threaten you in an alley you are about to enter in a few moments).

Actual and Potential threats each possess different qualities; some are avoidable, and others are not.

Muggers are not entirely avoidable, even if the chance of them appearing may be less than we think. What we do when a mugger attacks is to fight them off or flee from them. Either way, if we are lucky, we escape and we avoid the threat. When we cannot do this, and a confrontation is inevitable, our bodies appear to ‘help’ with a freeze response – one in which we are likely to acquiesce to being robbed or drop to the floor. We are still robbed, but we have a better chance of remaining alive.

A mugger will attack some-one tomorrow; possibly some-one not thinking about it now. However, as I am writing this, and you are reading it, the thought of tomorrow becomes inevitable; sorry about that, but there is a point to it. We worry about possibilities. Truth be told, some come about; most do not.

Worrying is most often focused on what might be – not on what is

The thing is that there are many things that can happen tomorrow – some we welcome, and others we do not. Recently, our communities were in ‘lockdown’ because of the public health crisis of 2020/2022. It remains a worrying time – made worse by the arbitrary and inconsistent decision-making and actions.

Tomorrow could be just another day, or it may be disaster to a member of my family. Sadly, in the course of writing up this website, in May 2020, one such threat arrived that was not anticipated at all.

However, the useful thing about the diagram, above, is that it shows us the several things we can do with potential threats. We can assess, anticipate and minimise the avoidable risk, e.g. go into self-isolation and ask our scientists to look our for a test and a vaccine.

With the unavoidable risks, we can only conserve our resources. I may have looked down my nose at panic buyers, but they were conserving their resources. What a shame it had to be at a price of more vulnerable members of our community.

HOW to conserve resources

ASSESS: this new arrival and fit it into a box of known conditions before the next comes along.

ANTICIPATE: what is to be done. Our government may have been criticised for its timing and pace – easy to do – but it worked to anticipate and formulate novel policies in an unknown circumstance. Governments are as susceptible to problems relating to change, as you and I.

CONSERVE: when our fundamental safety is threatened, as it is now, then we will conserve. Interestingly enough, this is accompanied by governmental expenditure, as much as conservation. As I see it, we are spending to conserve lives and livelihoods. All that takes time, energy and attention that has to be taken over from other things.

In short, then, our response – by flight, flight or freeze – involves an immediate assessment of risk. Other times, we observe a threat and work to allocate resources to managing our behaviour or contain the threat.

AN EXPERIMENT WITH STRESS in our lives

Consider a time when you were under stress. Can you identify and write down information about the threat and your reaction to it. With the benefit of hindsight, are you able to notice how some reactions were avoidable, and others, not?

What could you have done differently at that time, in light of the diagram, as presented above?

What are good starting experiments? We have already touched on one opening move; to think-about-breathing rather than staying on auto-pilot.

ANOTHER EXPERIMENT: return to breathing evenly; not very deeply, but filling your lungs slowly and steadily. Try breathing in to a count of three or four slowly, which ever feels most comfortable. Breathe out in the same way, perhaps for a little longer, allowing your lungs to empty without labouring it.

Do this for around 30/40 seconds. When you stop the CONTROLLED BREATHING, and notice the results, it is likely you will feel a little more relaxed than before; just a little, but you can ‘measure’ your response using the SUD, as mentioned. Just to revisit it briefly, the Subjective Unit of Discomfort (or Distress), or SUD, is a ‘measure’ on a scale of 1 – 10 where 1 is the least level of sensation you can notice, and 10 is the worst experience of the sensation you’ve come across.

A SUD can be used to measure levels of feelings: sad, fearful, anxious or angry and so on, or a sensation in your body: a cramp, a stomach ache, a tightness of your chest and so on. Do not justify your SUD. Aas emphasised, it is subjective; there is no need to provide objective evidence for it. However, it can be very helpful in letting you know whether a particular feeling or experience is rising (toward ten) or fading (going down toward one).

The thing about a feeling or sensation is that it can only stay the same, get worse or lessen. The body is wired to make it so. It helps to know which it is!

Do not be troubled if it is difficult to sense any change; there may be none, or you have need to practise more to become more sensitised to what is happening in your body. That’s not a criticism, simply an observation on the different rates at which all of us adapt and learn. All I know is that most people, some of the time, will observe a change.

As you practise any small, safe experiment, it may help ‘measure’ the changes you just notice.

AN EXPERIMENT with discomfort

When you next find yourself in an uncomfortable place, say, after an argument or a shock, stop for a moment and register what the emotion or sensation is and then label it (anger, fear, despair, anxiety etc). In the case of sensations, it will be well to locate it in the body. Some people can even give it a size, colour, shape or texture. If that is possible, and it helps, use this extra data.

Identify the Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD) for all or any experience that is right for you. Then take that half-minute to do some controlled breathing and see if the SUD has changed or stayed the same.

When you have completed this exercise: stop and gather SUDS, and any other information that seems helpful to you. It may help to write something down. Have some post-its around you as these events can arise unexpectedly and unpredictably and in odd places! Note such things as:

- where you were;

- who you were with;

- the time of day, even the weather conditions, if it is relevant;

- what was happening just before the event, and

- what is the apparent consequence of the event.

Faced with the results you have generated, consider: In light of what I now know, what might I have done/could I now do that will reduce my SUD by one point or even a half point (for example, from a 7 to 6.5). As you consider this key question – one that you can repeat regularly – you will begin to discover a creative side of yourself waiting to experiment with some different actions. Some things you do will visibly work and sometimes there will be a mixed set of results. Be aware of the small victories and small defeats you are noticing. Acknowledge them in some way or another.

Make a point of noting down your actions – successful, or not – and consider when you might be apply them again. Note down any further results arising from your own actions. Notice if you feel irritated by things that seem to go wrong. A note on irritation: I’ve mentioned this a few times. It is likely that you’ve become irritated by this blog at some time, before now.

THEN COMPARE THESE RESULTS USING AN EXPERIMENT WITH TODAY

Recall how you have used this website up to now. Remember prior experiments on just noticing some of your reactions. When did you have a negative feeling about this website or the safe experiment you initiated?

Now – you have a choice: if it is something I have said or suggested, then you can let me know. Please do that. If I can change my own behaviour, then I will.

The alternative is to recognise one of the few facts that exist in my world of psychology: the feeling is yours. True, feelings can be transferred but that’s a natural human defence – when you are tempted to think your current feeling is mine – or some-one else’s – but it isn’t.

More importantly, it is easy to blame me or A N Other for it. This won’t wash; my behaviour might be unhelpful – and you can draw this to my attention to that experience – hence option one, above. However, I am not responsible for the emotions you feel inside your body.

If that was so, then everyone would react in the same way, and experience shows this is not so. Also, do you recall how quick we can be to remind others ‘don’t tell me how I feel‘.

You may want to know how breathing control is so effective. That’s an important question, and the good news is that it has nothing to do with psychology. It is much more to do with your physiology.

I was not sure how much detail to put in here; physiology is a complex subject. I am not an expert in it and the scientific language can be off-putting. Even so, something has to be said: do ignore the following section if is seems unhelpful; you can come back to it at anytime. I have already placed much emphasis on doing things rather than expanding knowledge!!

THE TWO SIBLINGS

The key features to consider are the older and younger parts of your brain and, more particularly, the way in which they talk one to another. When the conversation runs smoothly our central nervous system is working well; when the discussion is jumbled and at cross-purposes, things get difficult.

This internal dissent tends to unsettle our AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM.

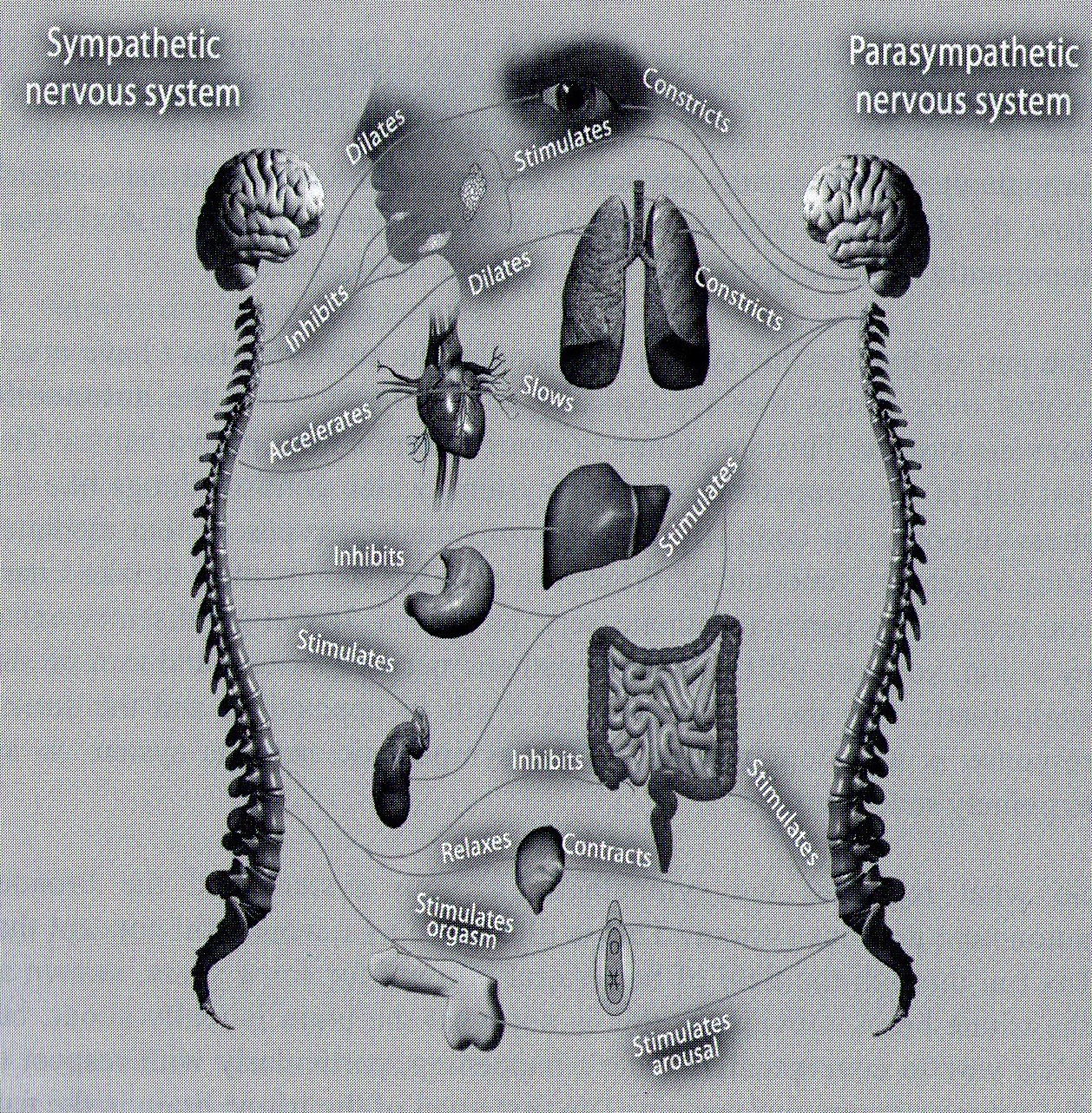

Here is a diagram:

Notice how some ‘balance’ is obtained in our system by bodily reactions that, at one time, stimulate our organs and, at another time, relax or inhibit those same organs. Different neuro-transmitters are released in different circumstances – when we are elated or fearful, for example – and these can have a large impact on our behaviour.

You can ignore all this, but the one thing I would ask you to remember is that the simple act of controlled breathing tends to help us calm and relax our autonomic nervous system.

It can slow the heart and the lungs down. That’s why I ask you to practise it a lot!

The role of the Amygdala

What other part of our body can be calmed? Answer: the Amygdala – a centre on our brain that enables us to generate and dissipate high emotion.

This brings me to one result of over-stimulation of all our systems: that most common of feelings – depression; a condition that can affect us to a small degree or, indeed, become disabling and destructive.

Note, I say over-stimulation. Very often depression is seen as exhaustion and under-stimulation. That IS how we often experience depression, but I want to stress that we get like that because our system is over-doing things.

It is working too hard to defend itself and that can only continue for so long without some adverse results.

Just noticing feelings of depression

It can leads us to think that life is not worthwhile; I say more about this sadly-frequent human response.

Common symptoms of depression

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness, pessimism

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, helplessness.

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities that were once enjoyed, including sex

- Decreased energy, fatigue, being “slowed down”

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, making decisions

- Insomnia, early-morning awakening, or oversleeping

- Appetite and/or weight loss or overeating and weight gain

- Thoughts of death, self-harm or suicide; suicide attempts

- Restlessness, irritability

- Persistent physical symptoms that do not respond to treatment, such as headaches, digestive disorders, and chronic pain.

The degree and intensity of our experience of these symptoms will vary greatly from person to person and from time to time.

The problem with ‘treatment’ for this condition is that the recommended experiments are the ones you may well be least inclined to try out. It is for this reason, in my view, that it is so common that we will seek a quick ‘fix’ -through medications from a doctor. Of course, if you are in doubt about your symptoms do consult your doctor. That said, a good doctor may well be reluctant to give a prescription if s/he can see there is a more practical step you can take in your everyday life.

Some common-sense experiments in the face of depressive feelings

revisit the idea that any task can be broken down into small ones. Do this, and set some priorities when ordering your tasks.

do what you can, when and as you can.

be with other people and confide in someone. Let your family and friends help you. This is usually better than being alone and secretive.

design your experiments around the assumption that people rarely “snap out” of a depression.

participate in activities that may make you feel a liitle bit better, e.g. mild exercise, walking and ball games; gardening and the like.

participating in some social activity may help.

expect your mood to improve gradually, not immediately. Feeling better takes time. People can feel a little better day-by-day.

it is advisable to postpone important decisions until the depression has lifted. Before deciding to make a significant transition – change jobs, get married or divorced – discuss it with others who know you wel,l and have a more objective view of your situation. Let your family and friends help you.

affirm to yourself that positive thinking can replace negative thinking. Negative thoughts are part of the depression. When the condition has lifted you may wonder to yourself how you could have thought that way.

Take the results of any experiment and reflect on how your thoughts and beliefs altered over time – sometimes to a less happy place and, other times, to a more tranquil state of mind.

Consider how different are your own reactions to other people around you when you are well. Some people have found it helpful – when well – to write to themselves a private letter only to be opened, when and if, depressed feelings return. What differences might emerge when the content of the letter is read when we are feeling bad?

One helpful experiment that might help with feelings of depression is finding a SAFE PLACE.

AN EXPERIMENT TO CREATE YOUR OWN OF SAFE PLACE

Establishing a safe place is such an important experiment that I have developed a page to this feature. Here, in brief, these are considerations you can include:

- Finding the right POSTURE: sitting upright, looking straight ahead, hands on knees or upper leg; both feet set firmly on floor.

- Starting to THINK ABOUT BREATHING: with the mouth closed, breathing in to the slow count of around three; in through the nose and out through mouth.

- After 34-45 seconds, starting a BODY SCANNING (BS); observing the thoughts, feelings and sensations that arise, noting, where helpful, the Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD) level (0-10).

- Taking steps to reduce the tensions you observe through any strategy available to you in this website or other self-help material.

- USE COUNTDOWNS to increase you state of relaxation. It may help to focus your eyes on a upward point – without straining yourself – say, take a look at a small picture or ornament up on a shelf (not down).

- USE FURTHER COUNTDOWNS to travel, in your mind’s eye to a ‘safe place’

- Do this by MAKING CHOICES – where, in your imagination, now, or in your past, was there a place that helped you feel good. Look for a place without people in it.

- Work your way into the heart of your chosen safe place by looking around carefully. Note where you are, what you can see, hear, smell and touch. Deliberately keep your environment warm and peaceful.

- JUST NOTICE specific and individual details and remain aware of your experiences and sensations inside your body, NOW.

- PAY ATTENTION to ways in which you can create and sustain an image and experience that creates a feeling of calm and safety.

- PRACTICE SKILLS that enhance the warm and comforting emotions and sensations by locating a pleasing physical sensation inside your body.

When you are ready to finish this work, take your time to walk away from your safe place knowing that it always available to you.

Do not rush away and leave bits of you behind. If necessary, use counting up to step slowly back into your ‘real’ world.