In the world of small, safe experiments, it is possible to think that what we do is important. Our emotions may appear to be of less consequence. In practice, knowing how we feel can be central, if change is to become more possible.

An example of a connection between doing and feeling

I had the opportunity to work with some-one on an action plan for their recovery after an accident. This left them with permanent, visible scarring. It interfered with ‘normal’ functioning a great deal. The repair work by doctors had been completed, with the help of physiotherapists and other specialists. Indeed, with time, the disruption to daily living routines was reduced as the person adapted and used their creativity to develop novel solutions. Even so, problems with daily living persisted.

In addition, there were issues about things, often small things, that couldn’t be done any more. Asking for help was easier to say, than to do. Over time self-worth and self-esteem was undermined. The loss of functioning had an unexpectedly large impact on the client’s feeling state.

This account of the large and small losses – some evident and some less so – took time to emerge. These losses came with strong feelings and, were to become of much relevance in shaping the ‘scenic route’ toward recovery.

So what is known about that scenic route, as far as such losses are concerned?

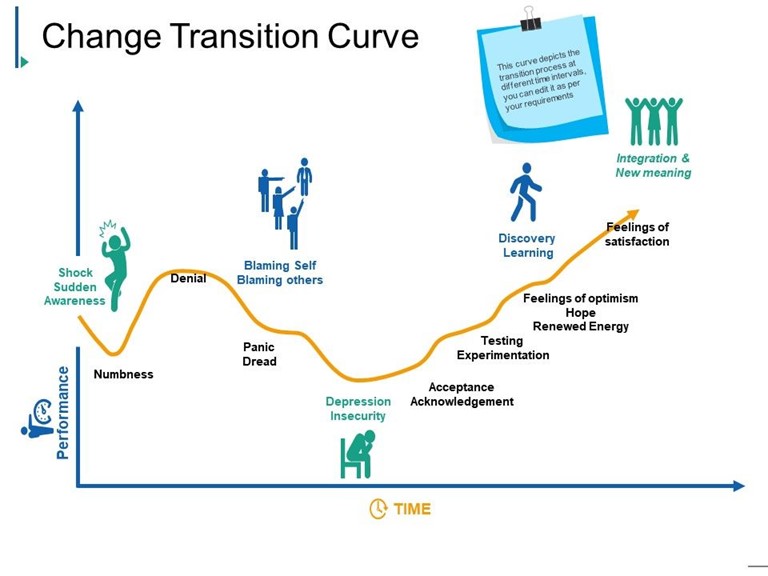

There is a pattern of feelings that many, but not all, people experience after a loss. These are summarised in this well-known transition curve:

It’s tempting to see these feelings as an inconvenience, or even an obstacle to change. However, that conclusion can be viewed differently. The feelings generated serve to stop us in our tracks. There is no longer a just perceptible change going on in our life. Instead, a large change has brought us up short. It is going to take time to absorb the practical meaning of what has happened. Feeling shocked is a great way to stop us in our tracks.

Literally, we stop still and do not move, if only for a very short time.

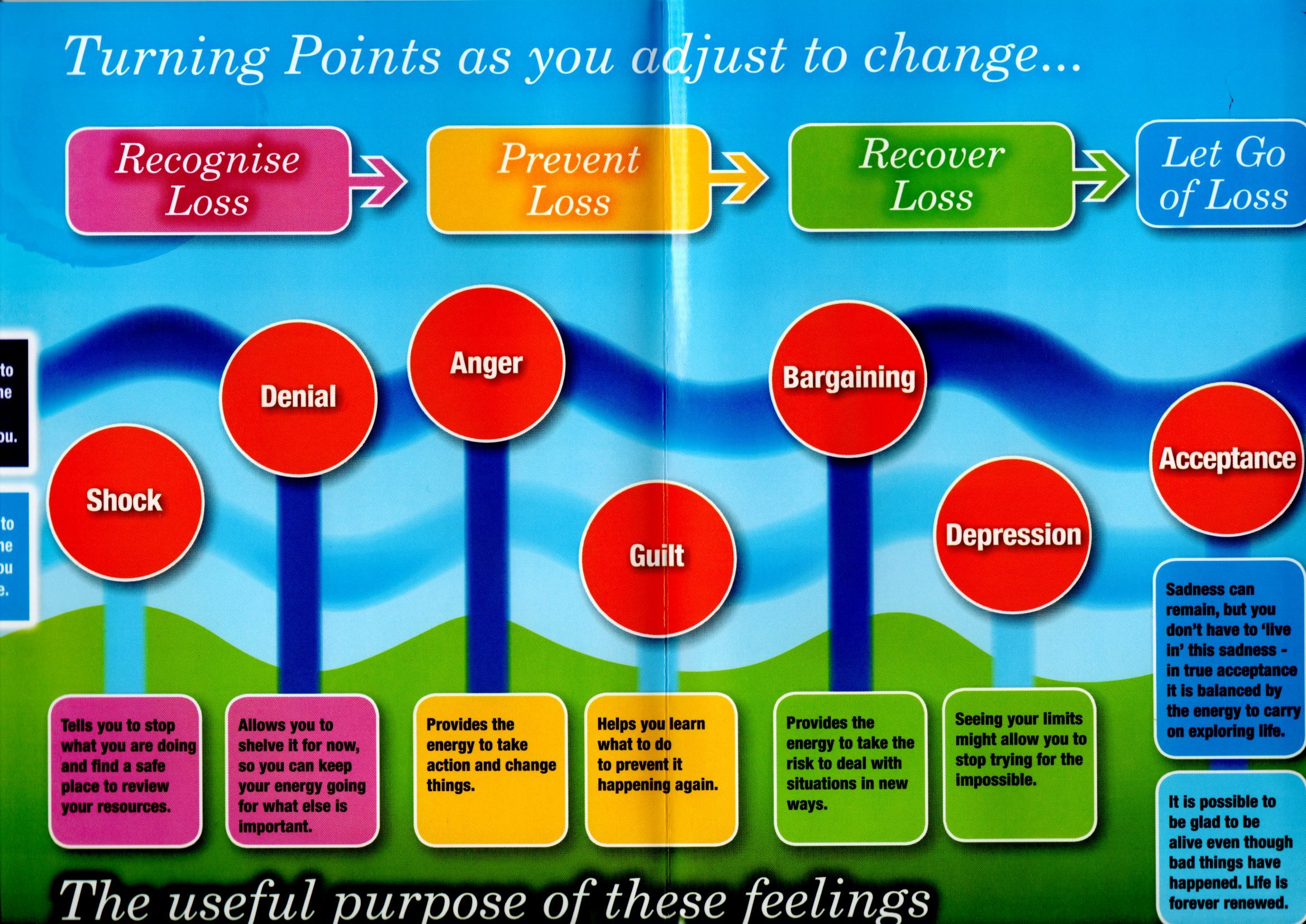

In time, it possible to see the way in which ‘unhelpful’ feelings can serve a purpose after all. Consider this illustration:

The message I read from Trevor Griffiths’ Emotional Logic course – is:

* shock stops me in my tracks. It may help me avoid getting into even deeper trouble after a major change.

- Denial serves a similar purpose by diverting our resources, now under pressure, to the ‘important’ things in life – sometime actual survival.

- anger can give me the energy I need to create change.

- guilt is a strange one; one that most of us do not want too much. However, guilt exists to stop me doing things. It can stop me taking socially unacceptable steps, such as committing a crime.

- Bargaining is there to foster small, safe experiments; putting one toe in the water to notice what happens. More importantly, it helps me avoid repeating history. At that point, I may be able to Think, Judge and Act – to work on my options for my own future. Bargaining is an important part of designing and implementing small, safe experiments .Bargaining is a time to notice what else might happen.

- Feeling depressed generally slows me down. That might be important when my renewed energy leads me towards options that might be difficult, if not impossible to achieve at this time.

- If I can slow myself down, and reduce feeling depressed, then I may be able to accept there are things I can do differently, and to know what I may be less able to do differently.

Part of that acceptance is having the wisdom to know the difference between what can be achieved, and what is not, now, within my reach.

This, and other ‘obstacles’ to moving on were labelled the “conservative impulse” by the social scientist, Paul Marris. His book, Loss and Change, had a profound impact on me when I was teaching. He was saying that humans are hard-wired to view change with caution.

In more recent years, it has become evident that our ‘hard wiring’ fosters a negative bias in our thinking. All this caution can help us to think twice before doing something. In my practice over the years, I have seen many people, in a time of crisis, regret an impulsive act that had large consequences when, for the sake of stopping, looking to the left and right, it might have been possible to slow down and take stock.

It may be an old text now, but Marris is still worth a read. This is particularly true if you consider his material alongside the work of Margaret Stroebe. Not only do the feelings that arise with loss have importance, but even feelings that are unpleasant to experience serve some functions.

A Safe experiment

Consider a time when your feelings seemed to be getting in the way and unsettling you ‘too much’. This page on this web site might help galvanise some relevant information. As ever, chose a time in your life that is manageable or make sure you have good support at hand.

Make a note: what happened and when did it happen? Who was involved and what were your relationships with any of the people involved.

Jot down just some of the feelings you recall from that time. You may find a safe experiment – here – of some help.

Take a break ……

…. come back and review those feelings. Consider – in light of the two illustrations above – what useful function did the feelings, particularly the negative feelings, serve?

What small difference could you make – and are you willing to make – to help the process along? Bear in mind my illustration of the Window of Tolerance (WoT) and how it highlights the demands on us when we seek to stay on the ‘scenic’ route to change.

At the end of the day, it is easy to act impulsively; without making a judgement about whether is it sensible to act in a certain way?. Good Judgement rather assumes we have gathered the valuable information and information-gathering assumes we can think about the information in front of us.

The small, safe experiment here is TO THINK, first, to notice our OPTIONS, second, TO JUDGE, third and TO ACT decisively at the end of it all.

EXPERIMENT: Write down on paper: This is an issue for me: identify that issue as briefly and specifically as you can.

Then give some time to thinking about that issue. Make notes or collate information from the library or internet, as fits.

Only then weigh up the options facing you if you are to address that issue? The Discount Matrix can be a tool to use during this small, safe experiment.

With the options in front of you, it may be more feasible to consider the judgement that needs to be made about those options.

Then, and only then, be prepared to act. Not procrastinate, but to act, knowing you’ve done all the judging and thinking that there is to do!!

Also, keep in mind who might be available to help you stay on the long and winding road as you complete this safe experiment. People who can support you, rather than see you slip into a ditch?