I have been asked to say more about fogging – a safe experiment.

It is a useful style of communication and I can fit it in, here, along with the broader topic of assertiveness.

Fogging

Fogging: is using language that is not expected. When I am criticised, it is difficult not to take it personally. In some ways, the other person knows this and, indeed, may even want to ‘stir the pot’.

If, on the other hand, I say something like “that’s interesting and I will think about that ….. what more can you say about that”, there may be a different response from the other person.

What I am saying here is potentially confusing. It is termed a ‘crossed transaction’ in Transactional Analysis (TA) and serves to divert energy away from repetitive and – often – unhelpful conversations. It can help interrupt ‘looping‘ as the other person is likely to do a ‘double take’. They may not like it, yet it provides a space in which they can consider what they said and what more specific things they can now say about it.

In your turn, you may not like them saying more about it, but still be prepared to make the invitation. You may hear something that takes you out of the highest level of discounting.

See if there is anything to be learned from a more considered or detailed comment you are likely to get.

Fogging without sarcasm

Another fogging device is simply to thank some-one for their comment. This is not as easy as it sounds. If I feel criticised, then it easy to be ironic or sarcastic with my ‘thank you‘ response! Therefore, it helps to add something: for example, “thank you for telling me [summarise what they told you]. What would you say I could do about that?”

Fogging is a practical strategy used in assertiveness training.

Let me present a few ideas around assertiveness, followed by some practical strategies from everyday situations. I give an example to consider at: Queries and Advice

Assertiveness

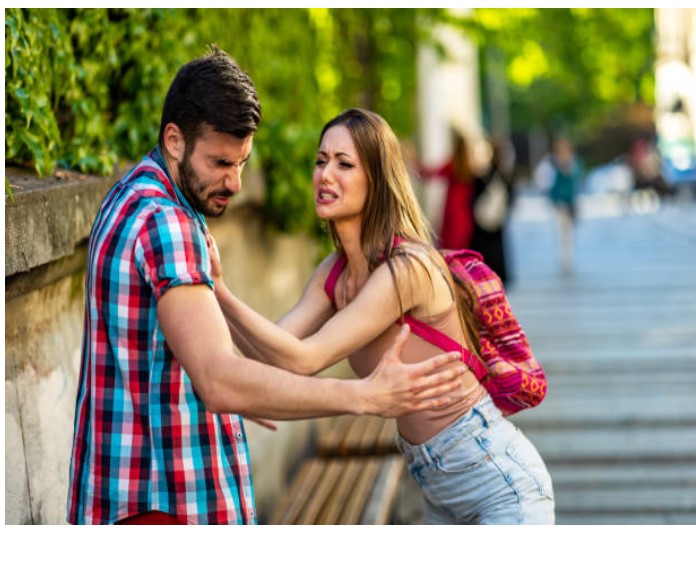

Assertiveness is often misunderstood. Sometimes it is seen as ‘standing up for myself …. but in an aggressive fashion‘. Neither party in my picture at the head of this page is being assertive. Let me say more about differences between aggression, passivity and assertiveness even if they are familiar to you.

These three different ways of behaving tells us a lot about how we go about getting our needs met. Each is a different strategy, even though most of us have a ‘favourite’ we are likely to use more than another.

Let me give some examples of these strategies:

Aggressiveness

* says ‘My needs are more important than yours’.

* is standing up for your rights in a way that violates the rights of others.

* is self-enhancing at the expense of putting down or humiliating others.

* may be manipulation – indirect subterfuge, trickery and subtle forms of revenge.

Passivity

* says ‘Your needs are more important than mine‘.

* is having difficulty standing up for yourself.

* means voluntarily relinquishing responsibility for yourself.

* invites persecution by assuming the role of victim or martyr.

Assertiveness

* says ‘We both have needs. I’ll let you know mine. You let me know yours. Let’s see what we can work out‘.

* is about being able to express your needs, preferences and feelings in a way which is neither threatening nor punishing to others.

* means acting without undue fear or anxiety.

* means acting without violating the rights of others.

* involves direct, honest communication between individuals interacting equally and taking responsibility for themselves.

So, from these examples, are there ideas around to help in the design of safe experiments?

ASSERTIVE BEHAVIOUR – some principles

… is joining with another, not arguing with them.

… is seeking clarity. This may require that we are not too involved; we can stand back. Note how Fogging is a specific experiment here.

Also, the ‘just noticing’ experiment helps here.

An Experiment

Consider a time, recently, when you did not get what you wanted. As you float back to that memory, do a body scan to just notice the thoughts, feelings and sensations that were around at that time.

As you do this, just notice any specific behaviour in yourself and others around you. Address that ‘small defeat’ question: ‘how might I do this differently next time?’ Do these observations and questions help identify a clear statement about any preferred behaviour that may bring change.

Further, does it help you be creative with the other person in asking for the ‘preferred behaviour’.

Finally, in drawing up your results, can you devise one thing you will do about this matter very soon?

This experiment will require you to focus on just one thing at a time. Notice how easy it is to distract yourself – and be distracted.

Here are a few more considerations that will help in the design of a next experiment.

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES

Notice the value of the ‘first person’ (the use of ‘I’).

How often has some-one said to you: “you do this or you did that“. It’s often irritating; is it obvious how the phrase becomes annoying? The statement contains an implied criticism and an implicit judgment, rather than a description of some mutually understood ‘facts’.

“I” statements avoid this; speak only for yourself. This helps us take responsibility for our own words and actions.

Look at, and listen to, the other person. In ordinary conversations it is normal to talk over one another and, most often, we get away with it. Indeed, as we listen to the other person we switch off even earlier than we realise – to formulate our own reply – before we even open our mouth!

However, one strategy, here, is to be patient and let the other person run out of steam. It does happen – most times!

Another way to speak to others involve the use of ‘minimal encouragers‘. These are simple to use, but so often we do not! Minimal encouragers are a few small words and a few encouraging gestures.

These steps are know to help others talk as they do not need to interrupt you and, indeed, they will often feel encouraged by you!!

Minimal encouragers might include:

- a positive nod of the head. Up and down, not side to side (think about it!).

- an encouraging use of hands that say ‘do go on’.

- attending the other person with ‘good’ eye contact. That is, not staring, but still. Do move your eyes around the face, as it might appear that you are staring. That will interfere with a ‘good’ conversation. Do not use these movements in a rapid and distracted fashion. If this is difficult for you, and it is for many, try focusing on the tip of other person’s nose.

- A body posture that is straight and still. Beware of slouching and letting your body drift away.

- a curious look on your face – not puzzled – but a look that says ‘that sounds interesting ….’I wonder what else you have to say …”

- noises or words that encourage include ….Mmm, do go on; wow, anything else? What more can you call to mind?

Further experiments

There are two others I’d mention; one is safer than the other!!

SAFE EXPERIMENT

Next time you are involved in any conversation at all, make a point of slowing down your own delivery.

Appear to be taking your time – being considerate.

Be prepared to stop yourself or edit your own words.

Say less, and listen more.

Use language with care; a language showing interest in what they have to say. See if that encourages the other person to talk more easily and openly. This may not happen; it is likely that they will notice you have changed – you are not your normal self – and this might well prove unsettling for them.

Do this for only a short time and be prepared to stop when things do not feel right.

LESS SAFE EXPERIMENT

Do the opposite. Talk even faster and more passionately in the conversation. Do not look at the other person; look around, here and there. Try using ‘you …’ in the discussion. These are typical ‘Stoppers’ to a good quality conversation. Do this one for a very short time in order to observe the impact you have on the other person! It is not likely to be favourable but it breaks the monotony in some situations.

EDITING OUR LANGUAGE

This is a more complex, yet still safe experiment

As you meet people and prepare to talk with them – attend to what you say and how you say it. Consider using:

- Personalise pronouns: that is, use I statements rather than ‘you‘, ‘it’, ‘we‘, and ‘one‘. Use of that personal pronoun, ‘I’, helps us to emphasise that the statement is only true in your experience and that it may be different for other people.

- Consider changing the verbs, or doing words. Where possible and helpful:

- i) Change “can’t” to “‘won’t” where can’t is not an appropriate restriction; you could do something, but do not want to. It says I am making a choice when deciding to do, or not do, something.

- ii) Change ‘need‘ to ‘want‘ and differentiate between need and want. This change helps me to be realistic my own needs, important and often essential things, rather than wants, that are desired, but may not always come our way. It can help to be clear about the difference between the two.

- iii) Change ‘have to‘ into ‘choose to‘ and ‘should‘ into ‘could‘. Again, these changes acknowledge that we are able to make choices and are not necessarily surrounded by obligations. We are responsible for those choices, and each one has a cost and a benefit.

- iv) Change ‘know‘ into ‘imagine‘ or ‘believe’ as we are too inclined to think something is a ‘fact’, when this is not the case. For example, we might state something about another person which we hold to be true, and others might not. It is helpful to differentiate between what is known, imagined, felt and thought in order to make clearer statements.

3. Change passive statements (“it’s not my fault …”) into active ones (“what I have done is …”): part of good communication involves recognising that we share a responsiblity for most (not all) of the things that happen to us. For example; ‘When I allow people to take advantage of me, I often feel angry‘, is different from: ‘Things keep happening to me that make me feel angry‘, in which the person blames things, situations or other people for how they feel.

4. Change some questions into statements: questions such as ‘don’t you think....’, are often indirect ways of stating ‘what I think….’. When a person is clear and direct about what they are stating, then they will be a better communicator – in our own mind and with others.

Beware Battle lines

Often, in a conflict, we will draw up ‘battle lines’. We tend to be against each other rather than with each other. This can lead to non-assertive or ‘win/lose’ ways of dealing with the conflict.

When two people respect each other, and the differences between them, we are more prepared to work towards an outcome which is mutually acceptable. This may be particularly helpful for a couple seeking to work out common purposes in their relationship.

Take one issue at a time: in most conversations, one thing leads to another. That can work out well until one arguable thing follows another. Avoid confusing one issue with another issue.

Stay in the present as long as possible. Using examples from the past to illustrate your point can lead to a distortion; the other person is likely to have forgotten or will remember the incident very differently. Consider the past as ‘for information only’.

6. Look at and listen to each other: often we avoid looking directly at each other and this can help us stop listening to each other. Look at – and listen carefully to – one other and we will hear more clearly and understand better, even if you do not agree.

This experiment is more difficult than it looks. How about simply trying out one item in one situation, and another item some other time!

The key thing is: what is the outcome

How can you improve the chance of reaching your preferred outcome? Does a particular result help you practise what works more often, and to avoid what stops you being a successful communicator.

Further leads

Actions that might work in a safe experiment