Regular readers and clients may well know that I find Stephen Porges’ work on the Vagus nerve fascinating. It has a number of implications for the way we design experiments. Here are a few of my thoughts on this.

My other entry on this topic is interesting, but it is a summary and it has few practical suggestions for the design of your safe experiments. So, here are a few more lines of inquiry.

The scenic route taken by the Vagus Nerve

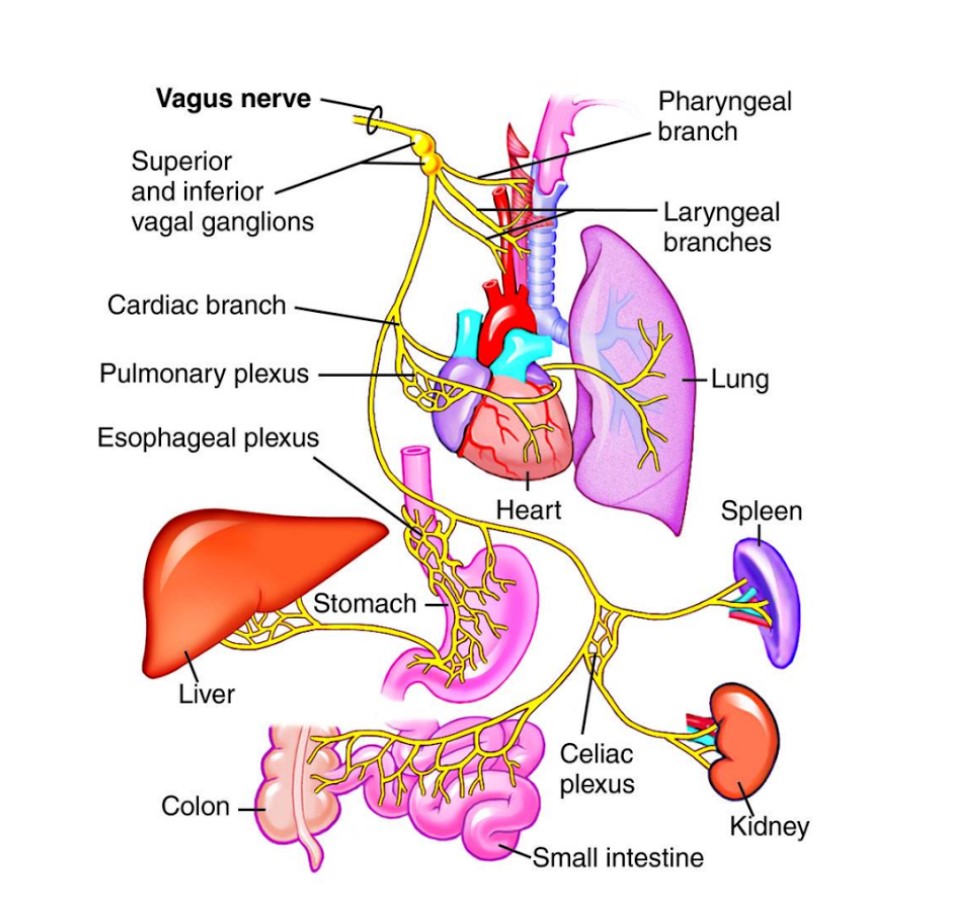

The Vagus nerve extended down the whole of the back-bone. It is not a single entity. It splits and serves different functions in so doing. Some vagal pathways support social communication, help to regulate our stress and enhance our resilience. Other vagal pathways are potentially lethal when sent into defence mode.

So let’s look at those divisions. Apologies for any simplification, but I am looking for the ‘do-able’ things – as ever!

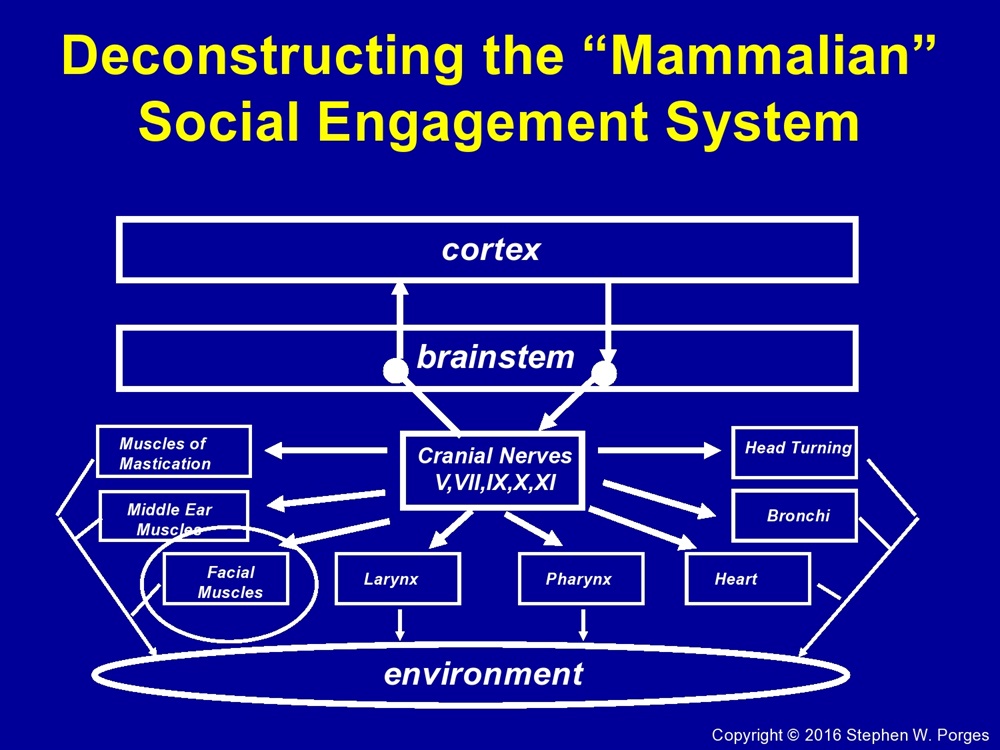

Here is Stephen Porges’ representation of mammalian social engagement. If it helps, and taking into account other things I have said on this web site, think of ‘cortex’ as smarter and younger brother or sister and ‘brainstem’ as not so smart and older sibling.

You will see from Stephen Porges’ diagram that the cranial nerves, as identified, impact on the upper body – face, lungs and heart. These connections promote social engagement as every small action and reaction around the top half of our bodies can impact on relationships with others.

What is the ‘social engagement system’?

Evolution has enabled our branch of the mammalian world to regulate our nervous system – to refine our social behaviour. It has taught the value of co-operation and altruism. This is achieved by a two-way neural pathway between the face and the heart – the Ventral Vagus. It helps send messages in the face and upper body.

Those messages convey interest in others and display the degree of our relaxation. These pathways foster our ability to trust, to regulate our body and to sustain a sense of well-being. We are more able to experience a sense of safety and a sense of belonging. They have impact on small facial movements, the gestures we make and the way in which we speak.

When danger and life threat are registered, that social engagement system will disengage. Our sense of safety is ‘translated’ into defensive responses we label ‘startle’ or ‘fear’ responses.

Flight/fight tends to be initiated and a tendency to be immobilised by fear arises as our whole system becomes dysregulated. The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) plays a large part in this process – and it can ‘hand over’ to the Dorsal Vagus when the going gets tough. This exchange can drive us to flag and faint; even help us die with grace.

In my YouTube reference you can see how the impala allows its Dorsal Vagus to help it immobilise and then, as his fortunes improve, to return him to Ventral Vagal recovery.

So what are the implications for the design of small safe experiments?

The aims of such small safe experiments are:

- to re-establish safety, and

- to notice our subjective experiences, and

- register our bodily responses, and

- to re-establish mobilisation or immobilisation WITHOUT fear.

HEALTH WARNING

Although I will focus on ‘safe experiments’ to reconnect your social engagement system, there may be times when this will not work and, maybe, not prove to be a good idea. Escaping and lying low are perfectly acceptable reactions if they help you survive.

So what’s to do? Here, there are some familiar steps to consider when designing a small, safe experiment:

- Any form of controlled breathing is more likely to engage the social engagement system, as it can slow me down.

- Body Scanning both slows me down and helps me to focus attention on my actual internal experience. True, that experience may not be a comfortable one, and body scanning still lets us know what is going on. It keeps us aware and stops dissociation – the tendency to disconnect from real experiences.

- Acceptance of self and others can be enhanced by affirmations such as ‘nothing lasts for ever‘ or I’ve survived.

- Creating curiosity: even small defeats can be a source of learning.

- Compassion to self and others: even in hardship, it can be possible to ask not why something is happening, but what drives some-one to react as they do.

- The Expressive Arts, and other forms of physical action.

All these strategies, spread throughout my web site, can help foster resilience – the ability to rise up in the face of adversity.

Specific small safe experiments to test out

There are a number of specific safe experiments that may help when we find ourselves or others sliding into defensive mode. These include managing:

Voice modulation and tone

It is no coincidence that the female voice has certain qualities. In the modern world, females are not now the only carers, but males can be at a distinct disadvantage in this area. A low or deep voice, a threatening voice, even a quiet yet menacing voice does not soothe and quieten. Therefore, it pays to give attention to:

Frequency

The rate at which we speak may need attention. We tend to speak faster when anxious. It is possible to slow down

Bass tones

Observation suggest that avoiding deep bass presentations can help. True, ‘squeaky’ might not do it either, but slower and more modulated ways of speaking are more likely to be experienced as calming.

Modulation

Put up and down into our voice seems to help. It can put rhythm and variation into our delivery. Maybe that’s why singing can be so helpful!

The quality of our vocal delivery: avoiding staccato and hectoring tones generally helps. Recall, if you can, the manner in which we speak to children and infants. Now that’s not a licence to patronise, but it does encourage speaking in short sentences, the use of concrete language and a more personal manner.

It is for this reason, that you see trained people using first names and brief sentences in crisis situations: often with gentle instruction. The aim, here, is to minimise confusion and maintain focus on a do-able thing.

All this can reduce our pace of relating (connecting to another). When we are in defensive mode, we do not hear or absorb even the simplest thought. We may not be able to follow the logical consequences of our actions.

Consider, from your memory, a time when you had to give bad news or, indeed, receive it. Most often, it simply does not ‘sink in’.

Delivery and the Window of Tolerance (WOT)

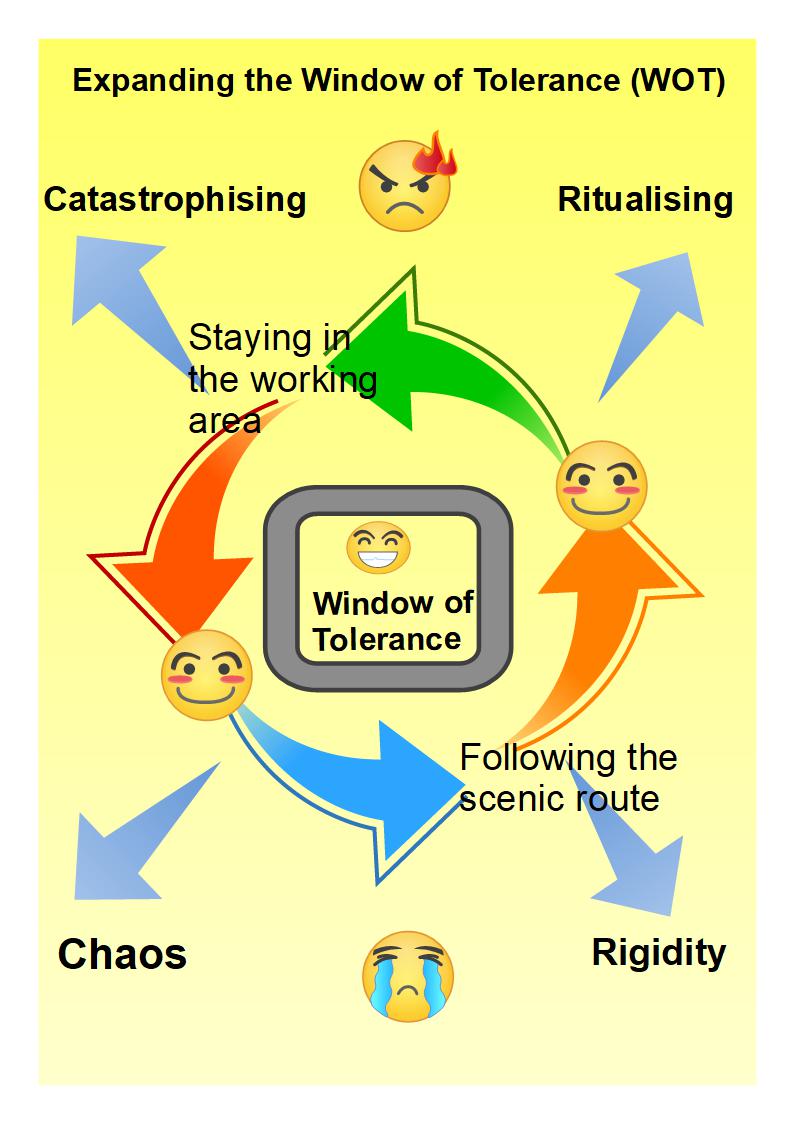

You may question when these safe experiments are relevant. It may be worthwhile reproducing this older illustration of what might be involved stepping out of our Window of Tolerance (WOT):

This diagram highlights that we are safe within our Window of Tolerance (WoT) – that’s today’s normal. That’s the Window located at the very beginning of our scenic route (top left, in the diagram).

Stay on the scenic route or divert to the extremes

I can safely experiment on the ‘working area or scenic route’ and design my ‘new normal’ for tomorrow.

However, I can over-step the mark. At that point, my reaction will be exaggerated. These over-reactions are listed above as being in states of Chaos or Rigidity, or Catastrophising or Ritualising.

These four states are just examples – convenient for my one-page illustration. There can, of course, be many other ways of over-reacting to events and experiences!

One very important ‘other reaction’ is immobilisation (an advanced case of rigidity, I would suggest). It is my experience is that each of us has a ‘favourite’ style of over-reaction; one that tends to one corner or to the left, or to the right, to the up or to the down, according to our personality – and the situation in which we find ourselves.

The safe experiment to consider here is what needs to be done to help me stay in the ‘working area’ and on the scenic route to a ‘new normal’. Just as important, however, is how I look after myself when I trespass into the extremities, as listed.