…. when many neurons ‘fire’ one after another.

I have been asked how we come to feel things and how do we know what we feel, and what ‘should’ we feel. There is an important supplementary question: can we broaden our sensitivity and identify a wider range of experiences we call ‘feelings’.

Here is my effort to offer some information, as it applies to a safe experimenter!

You will see, almost immediately, that part of the problem are the words we use to explain ourselves. Feeling is an old word used in many different ways – from I feel your are unreasonable (a judgement), to I feel you are a pain in the bum (a metaphor, for the most part), to I feel angry. Also, feelings can be sensations: hot, cold and pains or they can be emotions of fear, hate, happiness etc. We may have to consider all the above: The English labels for emotions are often ‘translations’ of experiences within our bodies.

Neuronal activity and action potential

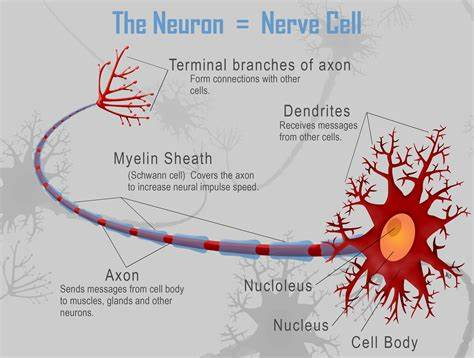

A good start might be to say we can only ‘feel’ after a firing of a neuron or nerve cell. At the head of this page, there is a technical representation of the processes involved when a cell fires. Not much help? Do read on and on and tell me if that helps!

Transmission of a feeling requires successive neurons to transmit a signal through other parts of our body. This can only happen when an electro-chemical impulse, called an action potential, is reached in one neuron – then another and another. This action potential is essential to activate transmission along the axon.

Here is an picture of this transmission:

These actions either happen or they don’t; there is no such thing as a “partial” firing of a neuron. This principle is known as the all-or-none law. Perhaps this digital feature has a role in the black-and-white phenomenon – just one of the thinking ‘disorders’ identified by the Cognitive Behaviour (CBT) school of therapy.

Feelings begin as sensations, but those sensations can only be noticed only if several neuronal pathways to fire up.

Prior to the Action

When at rest, the neuron is not idle. It is busy preventing or restricting sodium and potassium ions from moving. We do not notice these inhibitors when those ions are unable to proceed through the neuronal boundary.

That ‘resting potential’ of the neuron refers to the fact that a difference is maintained between the voltage within and outwith that neuron boundary. The resting potential of the average neuron is around -70 millivolts, indicating that the inside of the cell is 70 millivolts less than the outside of the cell.

At that point, no message is sent but the neuron remains ready to receive and send on a signal once that resting potential is broken by a surge of sodium cells.

During the Action

Once the cell reaches a certain threshold, an action potential will fire, sending the electrical signal down the axon. The sodium channels play a role in generating the action potential by exciting cells, and activating transmission along the axon. This means that neurons always fire at their full strength. The signal does not weaken or become lost. It is transferred to the next cell, and so on.

After the Action

After a neuron fires, there is around a one millisecond in which another action potential is not possible. This waiting period enables the neuron to return to its resting potential. Then, having been recharged, it is possible for another action potential to build up. This unconscious process of data transmission is called neuroception.

The human ability to neurocept does not require consciousness or awareness of an event. I will become more aware of the sensation as firing continues and more neural pathways are engaged. A domino effect builds up and the nature of our experience becomes more evident.

Through this continual process of firing, then recharging, the neurons are able to carry a message about the sensation to the brain where a human can make meaning out of the experience. In due time, micro-seconds, the sensation can be translated by me into an (English) word standing in for an emotion.

That process of ‘translation’ is call perception. Thus, for instance, ‘butterflies’ in the stomach can be interpreted as anxiety, and a rapidly beating heart as signalling fear or excitement.

Our Amygdala plays a large part in mediating the experience – and meaning we formulate as it enters our conscious awareness.

Making the unconscious, conscious

For some people, small safe experiments can make that conscious awareness more clear and coherent. The Body Scan offers a good beginning. The Johari Window is a useful explanation of how we become more aware of one another through feedback.

There is a further complication. As far as ‘sensations’ are concerned, the human body contains many different types of neuronal cells called receptors. They allow us to feel sensations like pressure, pain, and temperature. Receptors are small in size, but they collect very accurate information when touched. Then there are mirror neurons that foster a different kind of receptiveness, often related to our ability to empathise. For more information, do visit: https://exploringyourmind.com/mirror-neurons-and-empathy-wonderful-connection-mechanisms/.

Given my interest in trees, I liked their picture:

In addition, there is a useful page at: https://www.healthline.com/health/list-of-emotions describing the English translations we use to make sense of our emotions. That page could offer a number of leads for small experiments.

I am aware that I am confined to English as the medium for explaining things. I am reminded the Greeks had a lot to say about what we feel. Here are some examples I have been given:

Greek words for love

- Eros, or sexual passion. …

- Philia, or deep friendship. …

- Ludus, or playful love. …

- Agape, or love for everyone. …

- Pragma, or longstanding love. …

- Philautia, or love of the self

Also, the work of Brene Brown is worth researching and you could start with her website or her book Atlas of the Heart.

Some other safe experiments

Compassion focused therapy Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) offers an insight into how we can foster improved compassion for self and others.

Communicating with small, safe experiments https://your-nudge.com/communicating-with-small-safe-experiments/ where the role of ‘small’ changes in our way of communicating to others can make a big difference.

Talking ‘parts’ https://your-nudge.com/talking-parts/ is a page on which I describe ‘parts’ thinking. It offers alternative ways to talk to yourself with more compassion. There is a specific affirmation near the bottom of this page.

The Defence Mechanisms https://your-nudge.com/the-defence-mechanisms/ where I list some of the ways we protect ourselves from feeling ‘too’ much.

Other leads to consider

Actions that might help us do small safe experiments

….. even if action is not so helpful, after all