As my web site has been around for some time, the number of pages has increased. As I have gathered feedback from readers and experimenters, I notice a regular question that arises is: is there evidence for the effectiveness of ‘safe experiments’?

I’m going to say ‘yes’ and ‘no’, aren’t I!?

The ‘yes’ is that all the information recorded by readers and clients over many decades constitutes ‘evidence’, in my book. Some of this ‘evidence’ is included on this website.

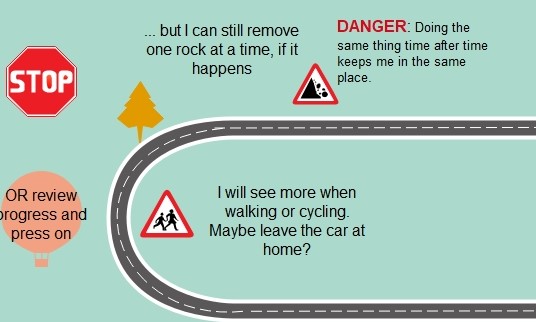

It’s a ‘no’ because the material is inconsistent – not replicable, by all and every-one. Yet, replication is a key feature of reliable and valid evidence. This troubles me less as my focus on is how you use the ‘evidence’ available to you. If you are troubled and struggling to learn from small defeats when the ‘evidence’ is difficult to follow, then your confidence may be undermined by that inconsistency. That makes it difficult to press on further down that scenic route.

It is but one ‘rock’ on the road. It can be overcome

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a key model for encouraging experiments (or homework, as some call it). It encourages substantial record keeping, maybe too much for some people’s liking. Even so, such records do provide detailed information about the outcomes of all our efforts. Further, there is a large body of formal research seeking to organise evidence in books and PhD theses.

I am not an expert in research literature although I can see it increases at an alarming rate. Keeping it at my finger tips as one of my professional strengths. What I’d like to do on this page is to go back to that word – ‘evidence’. What is meant by it and in what way does it help us to design experiments and promote the changes we want in our lives?

There are some misunderstandings to identify and I’d like to clarify what is useful ‘evidence’ when exploring human experience and relationships (as compared to evidence obtained in laboratories).

The ‘politics‘ of therapy

The respect given to medicine in the ‘healing’ processes has meant there is pressure to define ‘evidence’ the same in both medicine and therapy. This is a ‘political’ pressure to join the ‘big boys’, given the dominance of medical science in the field of research.

Nathan Beel put it well in a 2011 Paper entitled What can we learn from what works across therapies? He stated that:

“The medical model and evidence based treatment philosophy is seductive in its appeal when applied to psychological therapies. They offer hope that a correct diagnosis leads to a treatment that will result in a cure or, at the very least, remission“.

He concludes that the over-emphasis on identifying a ‘superior’ model draws attention

away from common factors between the many models that can lead to therapeutic change.

Don’t get me wrong; medical bodies and regulators are quite right to place emphasis on obtaining very solid evidence before they let a new medicine loose on the general public. There, the outcomes are matters of life-or-death, as I’ve said elsewhere. Often, only the strictest experimental design is put together. That seems quite right and there is little room for a Plan B or an opportunity to step back and re-design.

The Thalidomide scandal of the 1950’s and 60’s served to highlight the problems and to drive up standards in research.

There have been moves to improve the independence of staff involved in research studies as well. Despite all this, it is possible to manage, manoevre or plain manipulate research findings. The history of research financed by parties with conflicts of interest, e.g. the pharmaceutical industry, is littered with examples of this.

… and when it is not life-or-death?

However, this life-and-death feature is not present in the design and implementation of small, safe experiments, as I am describing them. The problem for measuring the effectiveness of therapy, using the tight controls associated with medical science, means that:

* useful data and results are sometimes excluded from research studies. For example, the experiments I am offering, and you will design, may have no visible result on some occasion. You can neither confirm nor deny your progress toward the objective under scrutiny at that time. Problem is, the same plan may well produce a different result on another day. What is ‘bad’ one time, may be ‘good’ or, at least, better another time.

* methods applied to the test of a drug are very different from tests we should apply in therapy. You can objectify a drug and make it a ‘subject’ of study. You can control that subject as tightly as you want. Good therapists do not objectify their clients. Effective researchers into therapy are ill-advised to try to do so. Indeed, the client is the primary experimenters, and the therapist more a guide. The good therapist will negotiate a preferred outcome – one a client wants – and one a therapist is equipped to help on its way. Then the therapist can help a client find a way towards that outcome. Research has to be able to focus light on how that process is initiated and sustained.

Evidence-based researchers say they follow ethical guidelines and that is all well and proper. Those guidelines exist to see ‘subjects’ are not abused. Even so, the key focus of medical research will be: did what we do to our subjects – in applying a treatment in ethical fashion – make people better? In therapy, it is not enough to simply assist people to get better; the way therapists help people get better so clients can continue that work once therapy is terminated. Achieving this outcome is central to the research in human relations. Ethics are more than a guideline to minimise the potential for abuse. How we behave towards one another is not an optional extra and yet what we do to move things on may involve some measured and informed risk-taking.

Ethical research into therapy should assess what works to ensure clients are respected. Furthermore, research can identify what negotiating and communications styles engage clients. The way a tablet is given to a patient does not usually impact on outcomes (but, again, there may well be evidence to contradict this assertion and I understand the ‘gold standard’ Random Controlled Trial (RCT’s) do, indeed, just that!

Research into therapy can study the validity and reliability of experiments but are the criteria to define these terms identical in the scientific and therapeutic environment. Now that is a BIG question. My short answer is, no, they are not.

The recording systems used by client and therapist could be assessed. Some may be more efficient than others in illuminating outcomes. But even then, effective therapeutic research identifies how the parties got where they did. It follows the journey from the design of a safe experiment through to observing its outcome and then interpreting and assessing the same. Research in medicine and science may ill-afford to study the journey; some people may die en-route and that is not acceptable.

so the ‘danger’ to clients in therapy is of a different order to the risks involved in medicine. Some people do challenge this, say, in relation to reports of ‘false memory’ syndrome, but problems of that order say more about therapists pursuing their own ideas, rather than enabling ‘clients’ to make the move that is right for them. That is not ethical therapy.

Once we can recognise that ‘safe experimenting’ is not what some-one else does to you, then it becomes much easier to look for ‘evidence’ that fosters incremental and fluid outcomes you obtain.

Furthermore, taking small steps in the implementation of ‘safe experiments’ assumes that we can step back from the result and decide to set off in a different direction. It is reasonable to consider that successful journeys depend on mistakes – or at least, noticing them. I would argue that our small defeats often teach us more than our small victories. Some folk say that there is no learning without mistakes: the bigger mistakes made, the bigger the lessons learned although there is a limit to that. For instance, see what Edmund Burke had to say in that topic (you’ll need to scroll down a bit!). Defining evidence relevant to small, safe experiments means it is necessary to legitimise the ‘moving of the goal-posts’. That is a ‘no-no’ in strict research work.

even when an experiment is a ‘small defeat’, things can be learned from the outcomes. As seen above, the strict assessment of evidence puts a negative value on ‘failure’ – some people even turns their noses up at Placebo effects. That cuts off a very large chunk of helpful research into ‘what works for whom’.

Strict research looks askance at my assurance: if it works, don’t knock it. Therapeutic research needs systems to define what is meant by ‘what works‘ as well as ‘what works for whom‘.

Research into therapy will find that what works with one person, and at one time, will not necessarily work for some-one else or a different time. Further, as I have said, we learn much from apparent ‘failure’. If it helps, take a look at my page on what might be involved in planning an end to therapy; doing that effectively requires gathering some evidence – but what sort, eh?

I have a suspicion that some researchers like to follow strict rules of research to affirm the neat and tidy outcomes needed to generate confidence in a new pill or procedure they have designed!!

The world of therapy is rarely that tidy and it will miss important things if it tries to be tidy.If you want to apply your thinking to this subject, how about seeking out your own definition of evidence-based research. The one offered by one website is:

Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. [my bold]

Do you wonder if the client view is really integrated in the sentiment that “external clinical evidence” is seen as part of ‘clinical expertise’? Sound research too often appears to be drawn up by a conference of experts. Too rarely is a client understood to be expert in themselves and that value needs to be at the ethical core of any research into the impact of therapy and how it works.

All this asks: what IS “best”? Notice how the practitioner may get included in defining ‘best’, but note that it is his/her “expertise“, that seems central. This is not new thinking; consider Tom Douglas’ comment in relation to Groupwork Practice (in a 1976 text by that name). Douglas was concerned that lack of information and understanding might mean group members would be troubled by having “little or no help or guidance, and many unnecessary mistakes and many avoidable hurts will be committed” (p.4). This is the view of practitioner-as-expert. This is very different from my own view; we can, indeed, get hurt, and yet still learn from the experience. We can make mistakes and mistakes, of a certain order, can be valuable life lessons. Note, if you would, the word ‘unnecessary’ used in relation to mistakes. Who’s saying what is necessary or unnecessary? Does emphasis on ‘small and safe'” let the individual determine ‘necessary’ with minimal risk. Can we not live with the consequences when we experience small defeats?

I use this example, as the groupwork I recall from the 60’s and 70’s placed large responsibilities on the individual to speak for themselves. Yet, in the few words from Tom Douglas I can be sense the subtle removal of power from ‘clients’.

If you wish to investigate this question further then colleagues from my old haunts in the north-east have something to offer. Their report contains an interesting chapter on what clients have to say about therapy.

Do their findings match your own experience of being engaged with counselling and therapy?

For a more thorough review of ‘measuring’ the results of our work, have a look at Scott Miller’s blog on:

How to design a safe experiment