Aggression is often hidden by a smile; not even a false smile, for that. It pays to be alert in uncertain situations, although ‘too’ much alertness, continuing for too long, presents its own problems.

Why now?

Since I started this website over six years ago, I have made only passing mention to two specialist professional interests; in critical incident management (CI) and the management of aggressive and violent behaviour.

I have been encouraged to revisit this topic by an invitation from the University of the Third Age (U3A). There are some practical experiments that emerge from this work, but whether they are small, or safe is another matter.

There is one an important, first statement to make on this topic.

The best you can do is have a ‘prepared mind’

…. as much as a prepared body.

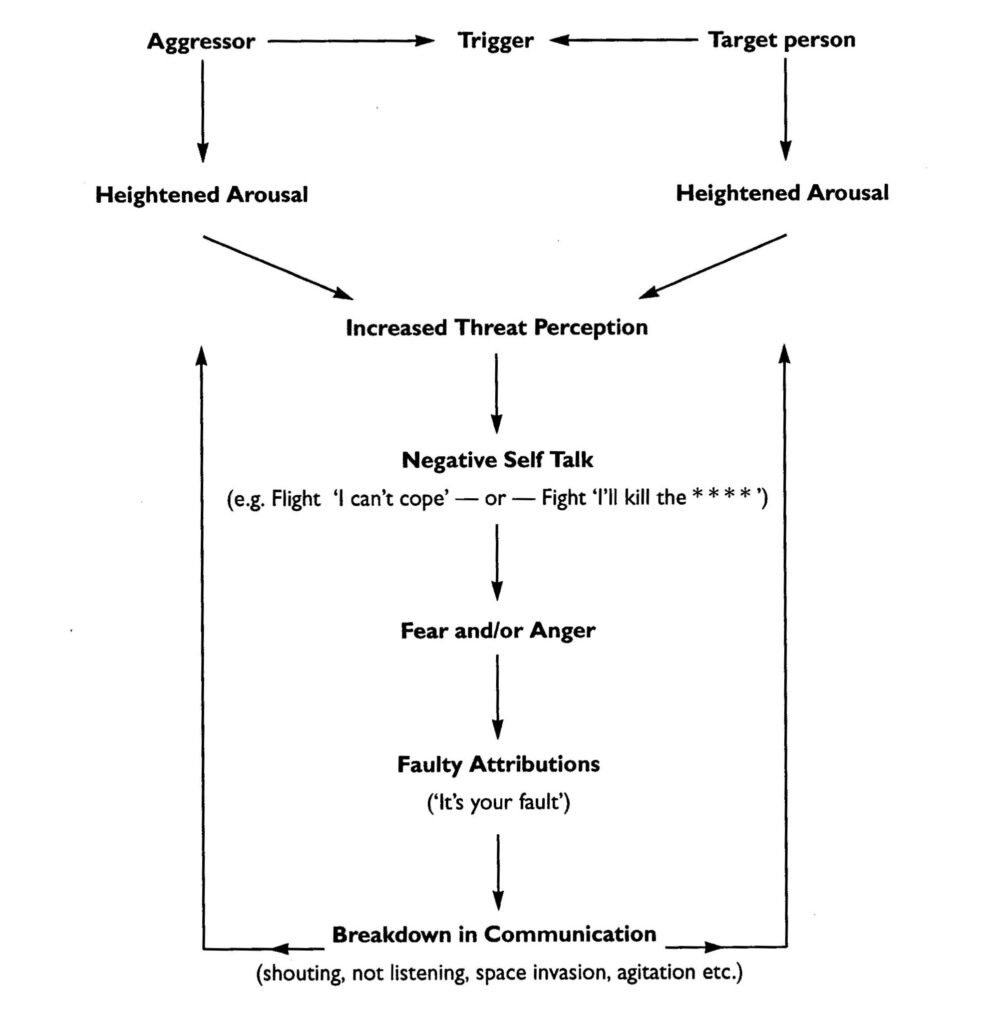

There is little that is right or wrong about rising emotions. They will be around prior to most aggressive or violent acts. Adequate management of potential violence – the form it might take – will be decided by many things, such as:

- the location: where it is arising (work, home or street?)

- social factors such as ‘pecking orders’, relationships between participants, group ‘rules’ in a gang or neighbourhood. The response of group leaders will have a different impact compared to a lower ranking group member.

- the availability of weapons ….. and not always the obvious ones. Tongues can do a lot of damage. Defining a ‘weapon’ is often limited only by the imagination of the participants.

- the impact of biology on potential participants in the run-up to an incident, during an incident and shortly afterward.

- complications arising from features such as substance abuse or an intention to rob.

- and then there is some psychology involved! Most information on this website is relevant!

All these features will shape the actual behaviour depending on what triggers exist, as well as the response of potential targets.

The end result?

Your actions will only have more or less impact on the outcome.

If everyone remains safe afterwards, that is a chance victory. If anyone is harmed, then that will be a chance defeat but you can increase the chances of a victory or a defeat.

Here’s what Peter Medawar says:

What does this mean in practice? How can you use ‘chance’ to make most of the situation you are in your personality and your skills.

What gets it started?

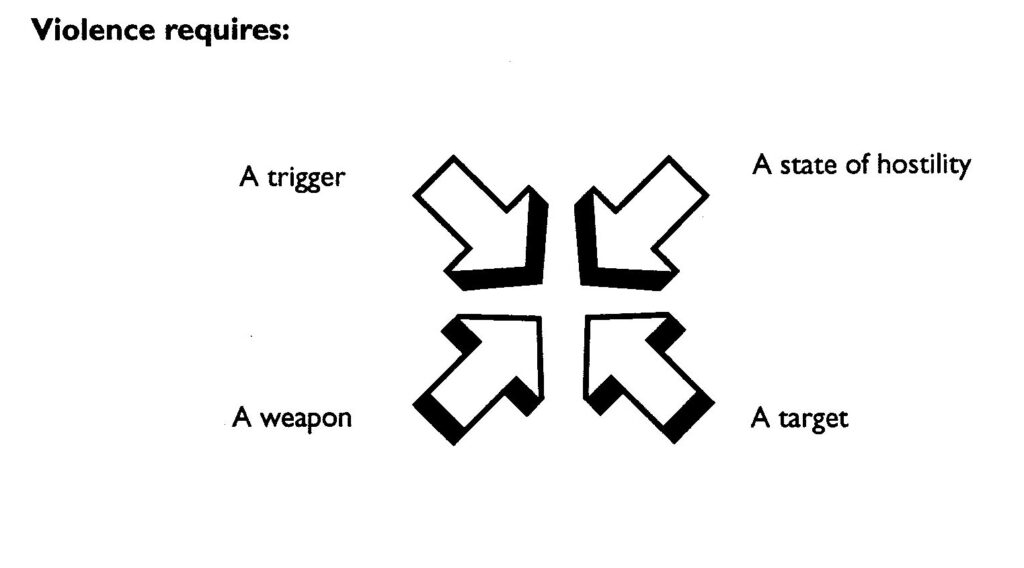

Experiments you design will need to consider the observation that:

Let’s consider an experiment relevant to each area. Maybe, if you are lucky, you can put two or more together:

Trigger: this is something that will ‘start’ things off such as loss of face or the production of a weapon. An increasingly aggressive look on a face can do perfectly well. Will you be alert enough to notice the ‘smaller’ signs?

Earlier intervention is more likely to be creative; last minute interventions tend to involve damage limitation. Early on, walking away is a potential experiment. If you cannot escape, then your imagination, alacrity and self-confidence will be needed in abundance.

Use any experiment on this website that relates to how you speak, and your communication with others. There will be tendency to speed up under pressure, so slow your delivery down.

When high arousal is around it is not easy for other people to think, but thinking is precisely what is needed at this point. That’s why the right questions are helpful, along with the use of first names. Most folk have their own name emblazoned on their mind so it is one connection that can help people to think, at a time when that person may act disconnected. Also, of course, it’s personal.

Avoid the use of ‘why’ questions as there may be no obvious explanation for what is going on.

Anything that describes what is going on might be useful, but the commonly used “what’s going on” is vague. “How come did ... [a specific thing] come about, Eric” may provide more focus, provided you use the first name correctly. For instance, using Arthur, my first registered name, would not crack it for me.

Consider the value of ‘commands’. Military traditions use commands to get a rapid and conformist response as soon as possible. This could work in unstable situations, e.g. “put that weapon down“, repeated as needed. The word “STOP” is tricky; it could be a trigger or a control. “Stop and think [or, look around you]”, might help more.

That said, personal words may be more powerful: “I am Robin; am I doing something that is troubling you, now“. “Now” is a useful word that keeps us in the present – if it is helpful to do that.

A state of hostility I will call arousal: all the experiments on management of our emotions, particularly high emotion, are relevant here. Re-visit some examples relating to breathing. Look at the impact of high anxiety on our bodies, and consider all the possible antidotes to those symptoms.

If a friend, and only a friend, is aroused you can demonstrate slower breathing and they may follow your example without being asked. If that does not work, then you could still ask them to copy you. Ask them to look at you (these words may divert their attention at a useful time). Avoid the TV script norm to take a ‘deep breath’; a long and slow breath is just fine.

Ask the person to look at you and demonstrate calming breathes rather than simply say ‘breathe’!!

States of hostility, as well as cultural factors, alter the impact of ‘body space’ on unfolding events. Too close can trigger more reaction; too far away is diluting and your ‘presence’ can get lost. There are three aspects of ‘distance’, or body space, to keep in mind: observing distance, negotiating distance and striking distance. As you can imagine, each one gets closer to the action and each one presents different opportunities and threats. You may want to do more research to consider how the different distances impact on your options and risks. These involve less safe experiments as effective action depends on your self-confidence, your speed and decisiveness.

A weapon: now you may think this is obvious, but there are nature’s weapons, e.g. our tongues and fists. Humans do not always need artificial aids to kick off or control a situation. When I was involved in training, I had a colleague who managed this bit as it assumes you know what you are doing! You may have some expertise in disarming people, and you may have to use it; but it raises the ante. Use weapons with care!

For the rest of us, humour can help.

A target: most often, there is some-one in the frame during an incident. Maybe it’s two or three people, if gangs are involved, but do identify the target in the frame. Does it include you? One of the important preventative moves – if you have reason to think there could be trouble – is to locate yourself near an entrance and exits – and use them.

That way, you can remove yourself and – preferably – any other target with some speed. Any fluent and confident move – an unexpected move – will lead others to do a double take. That might give you the part-second advantage that you will need.

Experiments with varying levels of ‘arousal’

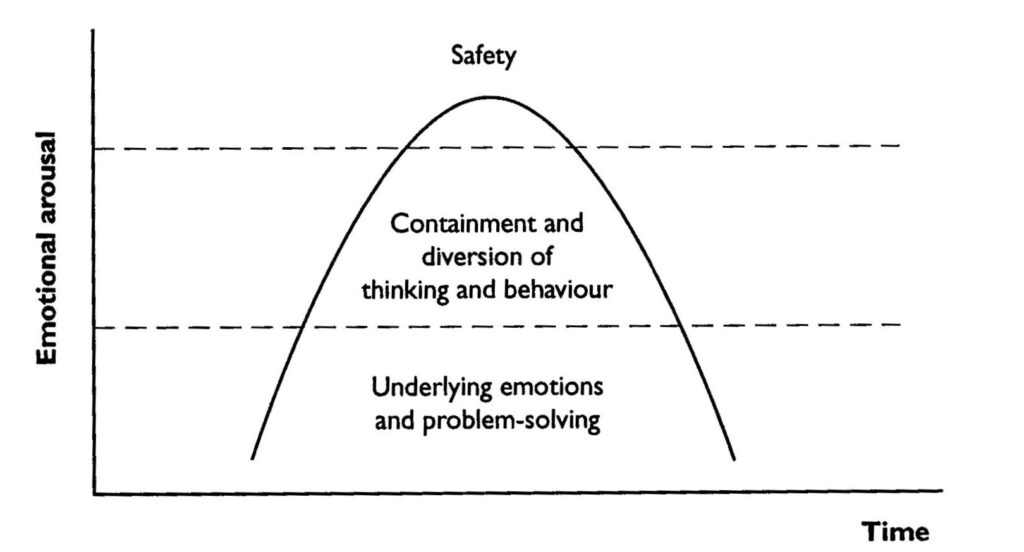

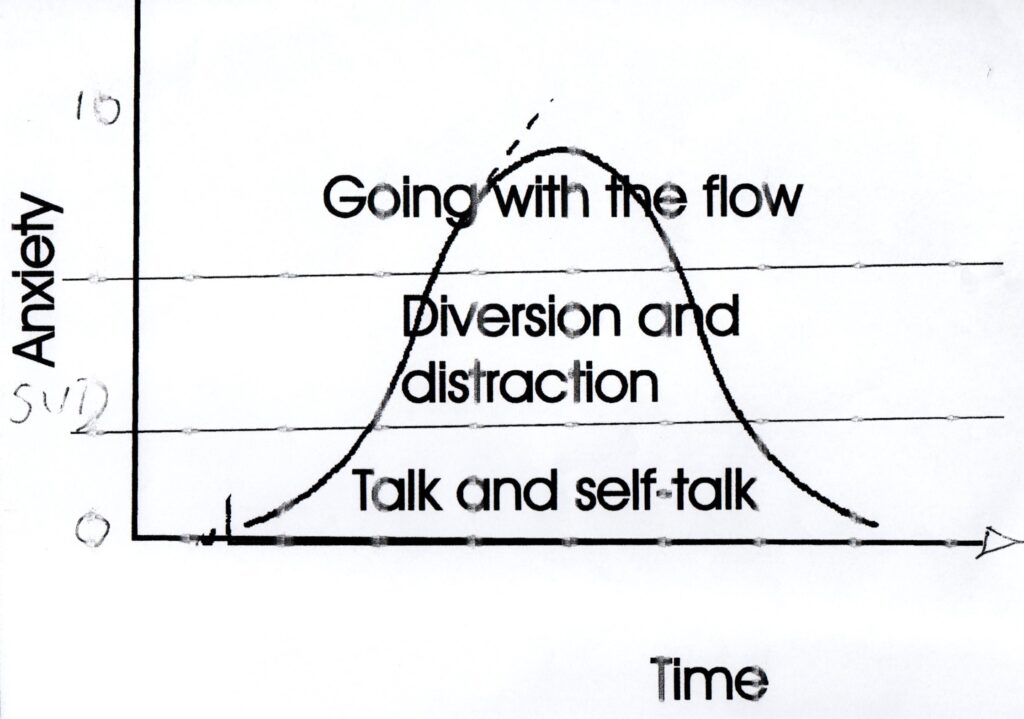

This page focuses on how different experiments help with different Subjective Units of Discomfort (SUDs). In unstable situations, SUD’s levels are going to be on the move all the time and there will be unpredictable ups, and maybe unpredictable downs. What will work will vary according to the changing, local conditions.

When you are in an unstable situation, it is worth having in mind a likely pathway for any increasing loss of control. Here is a flow chart, based on what I have said to date, that illustrates my point:

Some responses to this tricky scenario?

Each area I will now list can help or hinder the outcome of the event:

* our individual personality.

* the situation we are in at the time.

* the culture in which we are living. Globalisation has fostered diverse cultures yet undermined a sense of ‘common purpose’ in some communities. Of late, communal Project Fears have been circulated for well intentioned reasons (and some less well intentioned).

* then there is our chemistry: I’ve said plenty on this topic. I trust this website offers a number of experiments for the management of our feelings and the sensations being created.

* our values and beliefs relating to looking after ourselves, other people, and some of our points of view we hold dear.

* our relationships: what’s at risk here, between people?

Some relevant experiments (note small and safe is not included at this point)

Some relevant experiments: note small and safe is not so feasible at this point

Here are some categories for strategies used as the element of risk goes up and down.

Some specific examples

Low arousal

Broken Record: from assertiveness training: this involves attending to one specific action or goal that can be attained if the situation is to change for the better. There will be encouragement to shift the focus and manipulate the event. Broken record is a strategy that keeps to a do-able action through thick and thin.

Medium arousal

Boundary Management: this notion requires us to imagine a fence – or a psychological bubble – around each of us. It may be unreal, but the way it separates us from others has a large impact when high emotion is around. Therefore, where you stand and, indeed, whether you stand at all, is relevant. How close are you to the people involved and where is the exit?

High arousal

Contain or remove (self or others): these strategies require additional, specialist training as the response needs to be confident and decisive, yet proportionate to the situation. Actions will involve taking the initiative, usually in a team well experienced in making a shared response.

Common sense does not do it! Common sense is great for 99% of events and it allows for personal preferences. In professional management of events I am considering on this page – you are working with the 1%.

For instance, prolonged talking, or the use of threat, does not work with the irrational person. This can lead to failure to consider personal safety when the younger and smarter part of the brain is off-line making such action counter-productive.

Touch, so often used in effective communication, is not always helpful here unless it ensures quick and specific containment. This takes lots of practice of certain skills I cannot consider on this page.

Take a look at the last diagram, above, relating to everyday strategies for safe experimenting. Compare it with this approach described elsewhere:

In summary

Effective responses in times of trouble involve

- Anticipation: being alert to possibilities without exhausting yourself.

- Proactivity: being creative in order to contain and management fast-changing events.

- Probability: you will not always get it right. Forgive yourself when it goes wrong.

- De-escalation skills used systematically: only if you are trained in them!

- Physical restraint: only if you are trained in them and can have an eye on what you might say in the witness box!

….. but, above all else, realistic about your prospects relying on achievable actions.

Other lines of enquiry

When experimenting has to stop

When small, safe experiments falter?

The work of David Leadbetter from CALM Training