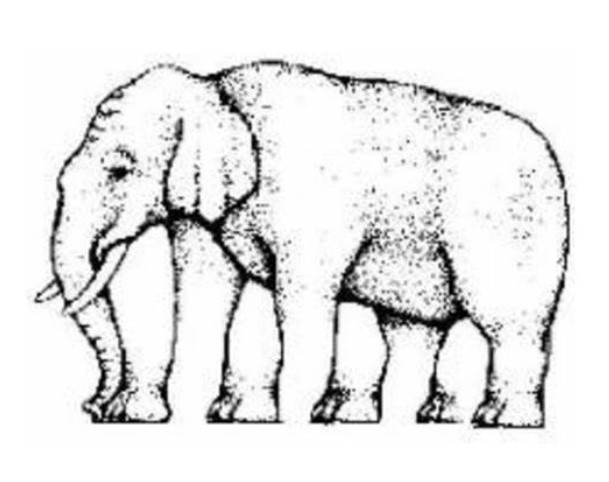

How would you describe this picture you see now?

Whatever it is, there is at least one more image in there. Some people pick up one, and others see something quite different. Few see two at the same time. Several of us get confused.

What we see is NOT what we get

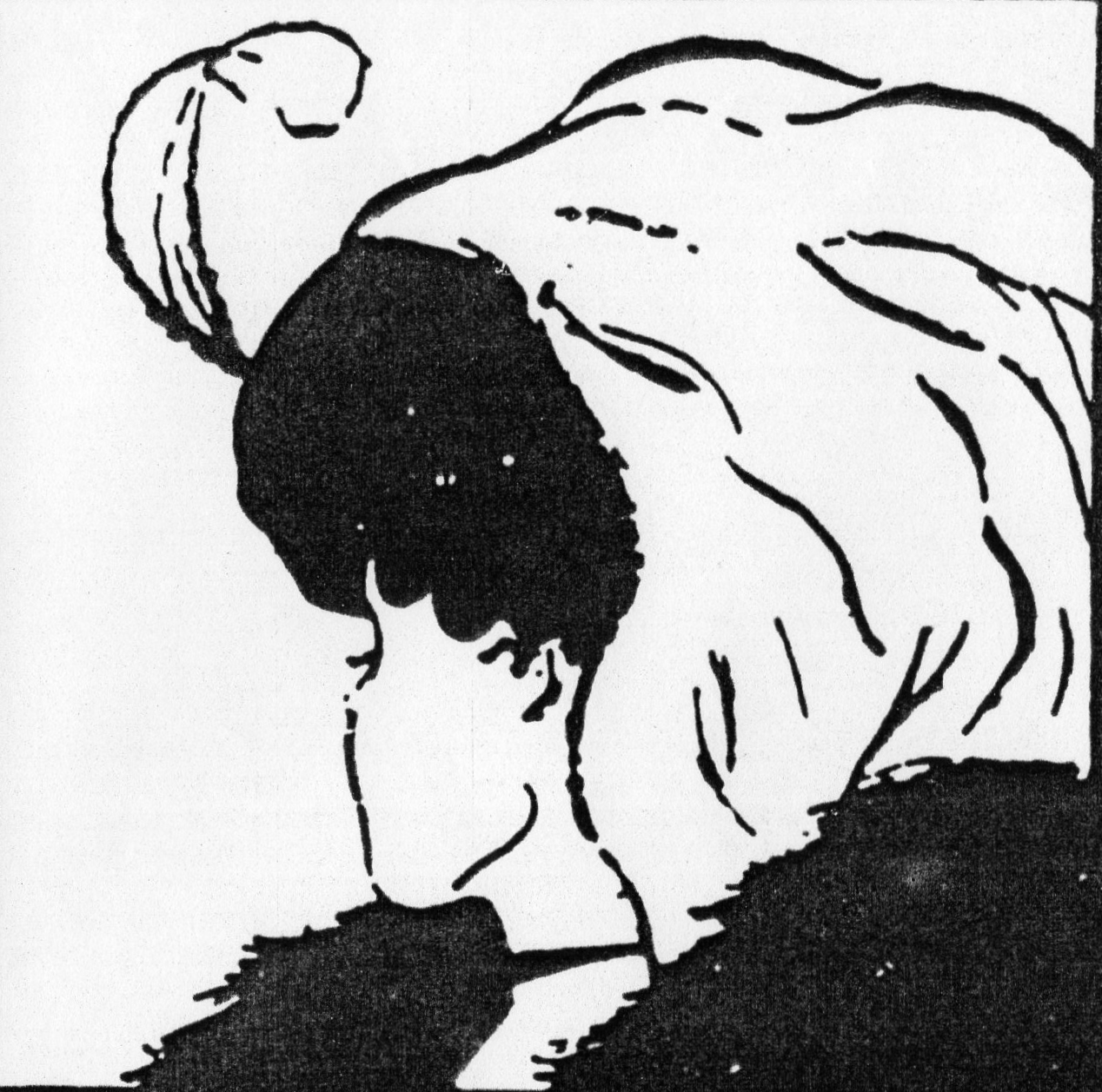

The point is that our ‘two siblings’ and our internal wiring do not work perfectly together. Our different ‘parts’ have got a lot to do and we can react very fast!

There is a cost; not only can we catch diseases, but we create problems for ourselves by seeking meaning that is not easy to find. We ‘confabulate’ – that is, fill in the missing data. This leads us to accept the first ‘meaning’ that emerges. We can jump to conclusions.

We can compound this tendency by sticking with a pattern once we have found it and long after it would be wiser to let it go. As a country, the UK has found this in the recent public health crisis when the government found it difficult to adapt to the very different characteristics of the Covid strains. We tended to hang on to a strategy once it is set in train. It proves difficult to change our minds and our practices. That can lead us up a cul-de-sac. I’ve a few of them in my illustrations of the scenic route to change.

In Transactional Analysis (TA), this life pattern is labelled a Script. The Script shapes the journey we take in our life, as though there were no alternative routes or destinations available to us.

So, looking at the image above is yet another experiment and it can lead to rather different outcomes for different people. If your life depended on getting it right, assuming we knew what ‘right’ was, then this could prove to be a unsafe experiment!

This is just one of an infinite number of judgements humans make everyday. Too often we assume that what we are seeing and hearing is ‘right’. As the years go by, and we get older, I know from experience that those judgements become more complex. Taking in information becomes more vulnerable to error.

A float-back safe experiment

EXPERIMENT: float back in time, maybe helped by your road map developed on another page. Find just one occasion when you realised, later on, that you had made a mistake. Choose a mistake that was not too serious; but big enough for you to feel something – and for it to have had an impact on later events. I have noted – on my scenic route illustration – that I have had victories that turned into defeats, and defeats that turned into victories.

Note down a summary of the incident, and the outcomes from it. Note down the ‘cost’ to you of any error(s). Consider how that mistake came about. If you find it arose from the actions of others, then put it down and find another event. Visit the page on Locus of Control for more information if this happens.

Find an error arising from your own actions or beliefs. Locate something that made you inclined to make that error.

What was it about you that led you one way, and might have led some-one else to a different result?

As you review your information, consider what might have been the stressors facing you then. The illustration, below, may be of assistance. As with other safe experiments, it can be useful to compare the picture that emerges from the past with the picture around for you now. This may help identify patterns of reactions in your behaviour over several years.

You can develop this even further by looking a little ahead in time. You may be able to write up something just a little bit different that can be done to avoid a similar result.

Moving on to a Life Planning experiment

Can this earlier experiment be worked into another safe experiment with a broader aim?

A general rule I have observed is that the earlier in our life-time that we lead ourselves up the garden path, the greater the impact of that event. The shadow cast is long and dark as this SWedish proverb highlights.

More recent errors can, sometimes, be put right more easily. They can cast a shorter shadow over our existence. There are obvious exceptions to this, especially when we reach a cross-roads in our life, but the rule is helpful as it explains why therapy, in general, can be so concerned with our early years and the impact of our early relationships with people who cared for us.

You can return to the welcome page, here, or scan down the extensive list of pages, below, to follow any other line of enquiry that raises your curiosity.