That said, there is one important issue to mention about the processes of change in our journey through life. In the world of therapy, much is made of walking alongside some-one as they skirt the obstacles. This stance helps therapists’ avoid taking the lead in that journey.

This is a sound principle, but one that is easier to say than to do. Saying it – or wanting it – does not make it so. Consider what I say to you in my ‘letter’.

A quantum view of therapy!!

Therapists like me, despite our training, still possess our own world view. That view shapes the way I think and act – often without me realising it.

All observers alter what they see, by the act of perception – that is, activity within the brain that ‘changes’ the nature of information after it enters our brain. This is not obvious in daily events but my child protection work helped me to conclude I am at my most dangerous when very assured about what I am perceiving.

It’s easy to talk about an event, at the expense of experiencing it. The model of change offered by Prochaska and DeClemente, warns us about that by placing store on contemplating on changes we are experience. See:

Their view, summarised in this illustration shows how the move from ‘contemplation’ to ‘preparation’, and into ‘action’, is a process that repeats itself time and time again.

This cautiousness in the face of change is sometimes referred to as the “conservative impulse“. It is a central feature of change – one in which defeats are gradually replaced by small victories – without abolishing the small defeats.

Furthermore, there is a bias in our language. There is judgmental language in many psychological accounts; this can make a therapist more confident in their opinions, than the ‘facts’ allow. Therapists, including me, can develop a persistent, if implicit, tendency to view what happens to ‘clients’ based on their own interpretation of what is ‘happening’.

Who makes that interpretation? Not the person experiencing the change.

Prochaska and DeClemente avoid this false sense of certainty by highlighting the faltering and cautious ‘try and try again’ nature of human activity discussed in my page on ‘relapse’.

Finding meaning

Interpreting, or finding meaning, is an active process. A therapist can have an important role in providing data to inform our interpretations. If I am to accept responsibility for the interpretations I make, and convey that to a ‘client’, then I need a commitment to the ways of adult learning.

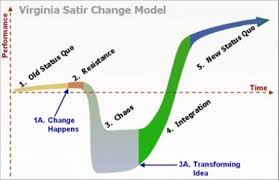

Let’s look at another change model from Virginia Satir. Does her approach help with designing and implementing small, safe experiments?

Notice how old and new normal is labelled old and new ‘status quo’.

You will see how, in due time, possibly in a flash, small victories can lead to insight – a sudden revelation – the “transforming idea” recognised in some models of change. Such insights be seen as ‘big victories’ but, in my view, they are not the big prize and they are not best relied on.

Small moves, back and forth, still get there and there can be many of them!

If you want to explore this further, and you like a challenge, then Thomas Kuhn’s book on The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, is essential, if difficult reading. It has been describes as the most influential treatise ever written on how science does (or does not) proceed.

Put this all together, and the outcomes demonstrate the power of systems thinking. Simply put, systems thinking operates on the maxim that the ‘whole is more than the sum of its parts‘ but those parts are needed to create a whole.

Transformation arises when I am able to fly in my helicopter and see the big picture, but I cannot do that until I have obtained my pilot’s licence. That takes a lot of effort – unromantic and painstaking – yet essential to any successful outcome.