There are several things that make humans, human. The ability to communicate is but one.

Then there’s all the stuff Porges has been able to tell us.

Then there is a rather a lot that philosophy has told us.

At the end of the day, humans communicate in a sophisticated fashion (some animals are pretty good at it as well).

So why is this ability to communicate rather important?

It seems to arise from the observable fact that one defining feature of humans is their drive to make meaning; so much so, we will seek meaning where there may be none. Our world appears unjust and filled with random acts of kindness as well as cruelty and harm. By and large, we, humans, are keen to explain away that word, ‘random’.

A Swiss psychologist built an entire experiment on this feature when he devised the Rorschach experiment. You may find it interesting to add this experiment to your own arsenal.

How might you develop this thought further?

COMMUNICATION

That smarter and younger sibling can get us into a lot of trouble from time to time. We may think we are very smart by communicating – especially if you can do it in several languages!

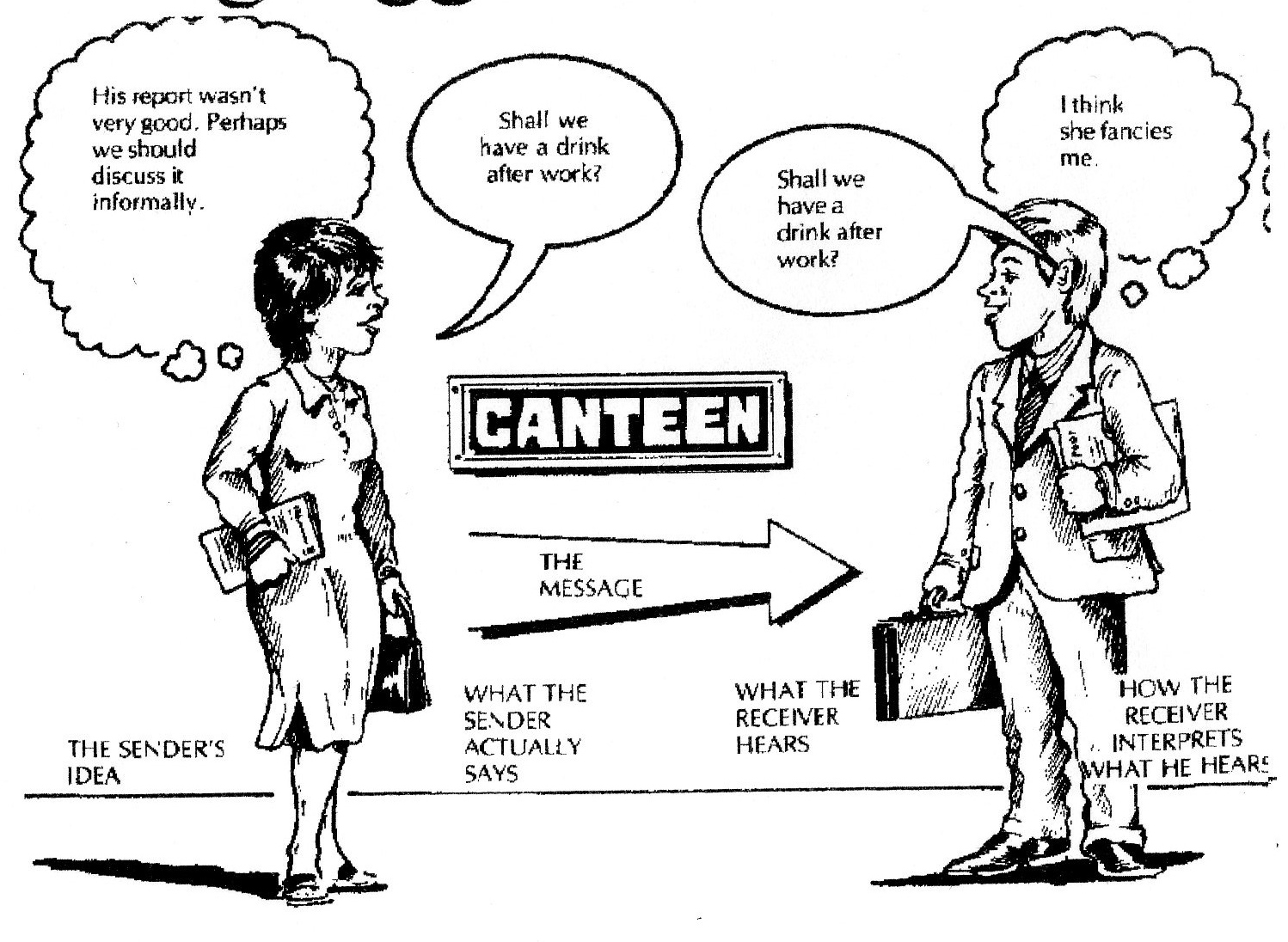

Unfortunately, it is not the words we speak that are really so important. Look at this picture:

Whose going to tell me you’ve never been there, or something close to it. A lot of problems arise when our communications are masked and indirect.

EXPERIMENT

Recall a recent misunderstanding with someone. Take a piece of paper and recall at least some part of what you said and what A N Other said; what was actually said.

Underneath, note your own unspoken idea behind your own words. If this is a tricky idea, have a look at what Transactional Analysis (TA) has to tell us about ‘ulterior transactions‘; you may need to scroll down a bit to find the information.

Speculate on what A N Other might have been thinking. Underneath that consider your own interpretation of A N Other’s words. This step is pure speculation but be open to the assertion that they did not interpret your words as you intended them to be.

Some questions

As you review your material, consider:

- How did I mask my own intentions from A N Other?

- What would have been the more direct words to use to convey my intention?

- How might I have responded differently in order to be sure about the actual intentions of A N Other.

You can undertake this kind of enquiry after your next misunderstanding given that it is only a matter of when this will happen – not if.

Transactional Analysis and communications

As I’ve said before, Transactional Analysis (TA) is very helpful in taking our understanding of our communications to a deeper level. This is a model using those three terms – often well know to us: the Parent, the Adult and the Child ego states. As sources of communication, each ego state can create a very different communication.

The model helps us understand how those communications often get crossed.

FURTHER EXPERIMENTS

…. a series of small and concrete possibilities

Assertiveness training programme can help us improve our own communications and you may well find something suitable via local adult education programmes in your area.

In the meanwhile, practise designing experiments to develop more awareness of what you say, and of how you express yourself.

Some specific words worth trying out

In your conversations, introduce some of the following; not all at the same time. Overdoing it can be counter-productive and rather challenging.

1. Use ‘I’ statements rather than ‘you’, ‘it’ or ‘one’.

When we use the personal pronoun ‘I’, we are acknowledging that the statement is true in our experience and that it may be different for other people.

2. Change verbs. Change “can’t” to “‘won’t” where can’t is not an appropriate restriction.

This change of verb encourages us to take responsibility and to be aware of what we can and cannot realistically do. Also,it says we can make a positive choice when deciding to do, or not do, something.

3. Change ‘need’ to ‘want’ and differentiate between need and want.

This change of verb encourages us to be realistic and responsible about our own needs and wants and to be clear about the difference between the two.

4.Change ‘have to’ into ‘choose to’ and ‘should’ into ‘could’.

These changes acknowledge that we make choices all the time and we are responsible for them.

5. Change ‘know’ into ‘imagine‘ in case your ‘fact’ turns out to be a fantasy.

Often we will state that we know something about another person when it is based on fantasy. It is helpful to differentiate between what is known, imagined, felt and thought in order to make clear and unmasked statements.

6. Change passive into active

We can place ourselves into a passive role when talking of things that are happening to us. . For example; ‘I allow people to take advantage of me and I often feel angry‘, is different from: ‘Things keep happening to me that make me feel angry‘. The latter statement appears to blame other people or events for how I feel. Here, the use of the first person (“I”) makes it easier to own what belongs to me. Notice how this example casts light on the issue of Locus of Control (LOC)

7. Changing statements into questions.

Statements so often assert an opinion, rather than a visible fact. Questions can be useful (with one exception: be wary of “why …..”). Questions stimulate thought and discussion. Other times, questions – such as ‘don’t you think….’ – are often indirect ways of stating ‘what I think....’. If you have something to say, say it and work with the consequences.

8. Take one issue at a time, and stay present.

Avoid confusing an issue with a load of others. Notice how, in arguments, often the past is used to identify a number of examples to illustrate a point. Using the past can lead to distortion and manipulation since the other person is likely to have forgotten or to remember that past very differently. Concentrate on specifying the experience you are having NOW.

9. Ensure that you understand each other. If you are unclear and confused about the issue, summarise or paraphrase what you think you are hearing. For example, ‘So what you’re saying is…., is that right?’

10. Affirmation work: Without being over-effusive, can you appreciate the other person? It costs little to acknowledge and appreciate them, especially if you can briefly describe to them what was said that has helped you. This is still possible if you feel criticised. See ‘fogging’ for more on this strategy.

11. Stepping Back: This safe experiment depends on the strategy of just noticing that something is important. That, in its turn, requires us to STOP-LOOK-LISTEN; to use the Green Cross Code many of us learned in primary school. In this way, we do not stop what we are doing – we START something else. By our intention to STOP-LOOK-LISTEN, it becomes possible to step back and watch, for a moment, what I am doing; not what others are doing, but what I am doing. I cannot alter what I am saying or doing until I just notice it. After that, I can decide to carry on, or to make the smallest possible change. That, in its turn, may alter the connection I have with the other person.

12. Use the Special Time safe experiment to negotiate some code words to help change. It can be tricky for partners to help you. Things they say and do can become triggers for intense feelings such as frustration and anger. Therefore, what is needed are some neutral words that you can both agree on; words that help them to direct your attention to the need to distract yourself – on a temporary basis – from an escalating problem.

These are just some elements to work on. You can consult whole books and web sites on this subject.

The problem with my experiments thus far is that the focus on words can prove misleading.

What we DO, rather than what we say so often speaks volumes.

EXPERIMENT: putting feelings second. That seems an unusual for a therapist to say! However, it can be a different step to take. Have you noticed how talking about feelings can add to some rows, e.g. “I don’t care how you feel” or “and what about my feelings” etc.

Try this ‘feeling-fact’ experiment instead. It requires you to respond quickly to some miscommunication by describing the actual behaviour that is troublesome, rather than the feeling it generates in you.

Thus, “I’m fed up with your nagging” becomes “when you tell me to sort out this bill several times, I feel inadequate”. It is vital that the words describing the feeling are spoken in a quiet and neutral tone. There may be some feeling leaking through, but it is important that the other person hears about the troubling behaviour first and then hears your present feeling as an account of your experience, not a complaint.

What is said first needs to be heard and too often our feelings eclipse the stated change we are seeking to make.

This is more difficult to do than it appears as it goes against the grain. Most of want to say how we feel and most of us are reluctant to be specific about the actual behaviour that is troubling us. I will say more about this under the terms direct and unmasked communication as we go along.

EXPERIMENTS WITHOUT WORDS

1. Eye contact: how I look at some-one can convey how I feel about them and what they are saying. It is a powerful self assertion to look someone directly in the eye – not wise with bank robbers – but we can give away our power by looking away. When we look directly at the other party, we communicate that we are alert. That said, too much gaze and eye contact can say other things – it can be challenging and over-intimate. The Other may feel embarrassed by it.

2. Posture: how we stand and sit communicates how we feel about ourselves and what we are saying. In my village, I have been described as ‘laid back’ and that has arisen, for the greater part, from my tendency to slide down in chairs with legs outstretched. Not a pretty sight!

So, you will have noticed that too much of something has one set of consequences, and too little results in something quite different. Where will you place the balance?

3. Stepping back: this is a key small, safe experiment and one worth practising a lot. Often heated arguments bring people close together in a confrontation. In practice, it helps to step away, even if only a little bit. This reduces the risk of physical confrontation and, psychologically, it can help us keep a clear picture of the person and yourself separate from the issue.

4. Listen to other: most of us like to be heard. Our own ego can too often stop us listening and giving time to another. Problems arise when we feel impatient and speak over another person (that’s why I invite my clients to tell me to ‘shut up’ if needs be!). More importantly few people can keep up a flow of words for ever, so your time will arrive to speak and you so – in the meanwhile – you have lot’s of time to think of the words that will help the most. More importantly, again, that moment will arrive when the other has given off steam and they are less likely to be emotionally aroused. Use the SUDs experiments to monitor how emotional levels change as people talk.

Please note, this is not always true and different steps may be needed to protect or care for yourself.

5. Choosing your time and place. There may never be the best time to complete some important communication, but how you go about it is helped or hindered by the place and the time chosen to do it. Is there a neutral or more comfortable time and place to do what you want to do? In particular, consider how much time you want to spend on it; open-ended, is not always a good idea! Consider this: when the phone rings, it is only an invitation to talk. You can decide how much time to give to a call and it can help others to know what that time limit is.

TRAUMA: this response is a special case of internal mis-communication. It is then aided and abetted by some of our external communications. The ‘two siblings’, and the interconnected set of brain structures lying deep within the brain, can initiate mis-communication. Experiencing any shock and sudden discontinuity can do this, e.g. being hit, being involved in a bank raid or caught by a blast from a bomb.

It is vital, as a first principle, to accept that the ‘miscommunication’ may be a nuisance, but the ‘two siblings’ do not realise this. They are reacting to events that feel real and their reactions are intended to help and protect the body-mind. Unfortunately, in the 21st century world our reactions do not always return us to a sense of well-being. Bear in mind that the principal task of the brain is to make meaning and to mediate between our internal and external worlds; a divide that only too easily becomes out of kilter. In addition, there appears to be a neurologically initiated negative bias in our thinking and communication. This seems to be based on the idea that safety is best achieved by being wary.

One feature, not the only feature, of a trauma response is the intrusion or flashback; the ability to relive an experience as though it is happening now, in real time. There are two very different forms of this response.

Intrusive memories are vivid pictures, smells, sounds that are experienced as being very real, although the individual remains aware that they are actually recollections. of a traumatic event. Intrusive memories can often produce intense physical sensations and it is very common for people to try and block these memories out or push them away when they occur.

During a flashback, some aspect of a traumatic event is experienced as if it were happening all over again. One might re-experience sights, sounds, the presence of others, smells or things touching you. Any sensory information registered in the memory may be replayed vividly. Reactions like these tend to make people feel like they are ‘losing their minds’, or that their minds are playing tricks on them: they know logically the event can’t be happening again, yet it seems to be so. Flashbacks can be terrifying because of their unpredictability.

Both intrusive memories and flashbacks can be triggered by very subtle reminders in the everyday environment, such as a brief sound, a smell, or just a feeling. Both intrusive memories or flashbacks can make you feel very much out of control, especially because they seem to come totally out of the blue. They can elicit such strong physical reactions.

Some revision before any EXPERIMENT

If you are aware of any trauma response, see that you are properly supported before learning to manage it. A number of resources are needed to address this feature. That said, be confident that you can work at your own pace and don’t push yourself too hard.

Recall what I have said about feelings of discomfort and remember my re-assurance that such feelings are neither usually harmful or dangerous, even though this may not feel right at the time.

The aim of change here is for you is to find a workable place for those experiences and to regain some control over them. Trauma management can include these basic experiments before anything more sophisticated is tried.

For instance, use the anxiety model to explore and understand what is happening.

Also, revisit the arousal curve model to inform and plan interventions. You may need to scroll down to find the arousal curve on this other page.