This page may cast light on our response to events. Many of our actions have little to do with the event itself – what is happening. Often it is more to do with what we believe is happening or feel is happening. Sometimes it is not even within our gift to make it different as our neural networks have made the ‘decision’ made before we ‘know’ it (consciously, that is).

This does not mean “it’s all in the mind“, as can be said in a disparaging way. The brain and central nervous system is complex. Often it acts without consulting us, but with the intention of being helpful, even working to save our lives.

What I am about to say is a simplification and should not be confused with the truth. It is a representation.

Early research literature refers to the ‘Triune brain’ – a three part entity. The brain has a very ancient history and many more modern adaptations. This model of the Triune brain is, itself, of some age – proposed in the late 1940’s by Paul Maclean in the US.

For a simple introduction, consult:

https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/the-concept-of-the-triune-brain

but not accepted by all and every: see

https://medicine.yale.edu/news/yale-medicine-magazine/a-theory-abandoned-but-still-compelling/

When I am talking about this subject, I represent the divisions of the brain as:

YOUR SMARTER AND YOUNGER BROTHER OR SISTER, versus

YOUR NOT SO SMART AND OLDER BROTHER OR SISTER, and

YOUR PET CROCODILE

The information I am about to summarise may prove very helpful. Clients have said this material has helped them to understand the way their body behaves. More importantly, it helped highlight just how feasible and practical ‘safe experiments’ can be.

So, the brain consists of many parts, but for practical purposes and, for now, think of it as two brothers or sisters, often referred to as siblings. One is older than the other; another is smarter than the other. Rather crucially, one is faster than the other. Which is it?

Look at this photograph:

Consider the arm as your spinal column, connecting each and every part of your body to your brain. On the top of that spinal column, the first fist, there is the older and not so smart ‘sibling’. Surrounding that one is a smarter and younger ‘sibling’.

In this simple representation of your brain, the oldest part, the lower fist, has its origins in our pre-human existence. It even includes elements of our earlier mammalian form as we crawled out of the water millions of years ago – that’s the pet crocodile.

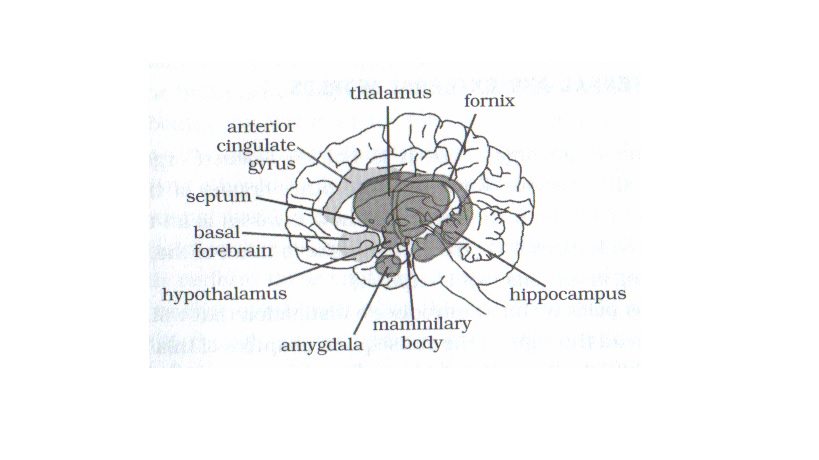

Over the ages, that old brain has evolved and changed and, now, those other parts providing more visible human qualities – the ability to talk, think and reason. The upper fist, surrounding the lower fist, provides much of that thinking and calculating part. It is often referred to as the cortex. There is a ‘switching’ station connecting the two – the thalamus – helping the siblings keep in touch.

EXPERIMENT: consider whether the lower (older) or the upper fist (younger) is the faster? That is, when the electro-chemical innards are at work, which one arrives at a course of action before the other?

Really, there is no contest, but it may not be obvious whether the smarter and younger sibling, with youth on its side, is quicker off the mark or does our more ‘primitive’ part get there? As you reflect on your information, can you consider why your conclusion is right; why is one faster than the other?

More importantly, what will be the consequences of the one being quicker than the other?

Write down some thoughts so you can come back to the important points here and weave them into any other experiment of your own making.

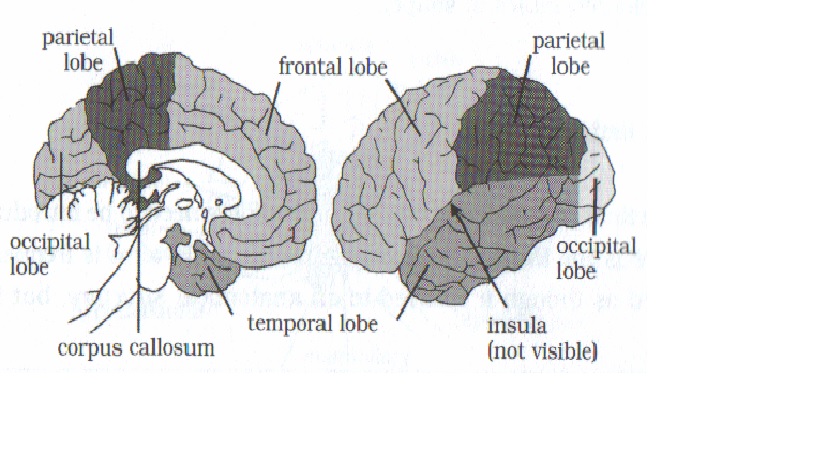

The photo provides a simpler and easier ‘map’ of those siblings. The reality is rather more tricky. In case you want to look into this more deeply, let me provide a different map:

The Two Siblings

Older, and not so smart

Younger, smarter

If all this detail is unhelpful to your experiments, then please pass over it and read on. There may be some more helpful detail available on this page. Otherwise, what experiments might come to mind? We will return to this theme of responding to our emotions again.

For even more information, see if you can track down:

The Brain with David Eagleman:

a BBC 4 broadcast from January and February 2016. The second of four episodes, on memory, seemed, particularly helpful. Look out for the use of a percussion section – a very practical metaphor.

INTERNAL SENSATIONS

So, these two ‘siblings’, and various other parts of our nervous system, are experiencing and responding to a range of sensations and events throughout the day and night, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, from our early conception to our death.

I will address the impact of sensations from external experiences later on. However, within our bodies, our muscles and organs are creating sensations via a vast array of neural pathways. The information going along those networks is meaningless without the brain helping us to attach some order it. This will be a key issue when our experiments address trauma-related matters.

The workings of the human body are complex but, in the experiments I will describe, I hope to show how the different ‘parts’ relate one to another. Also, I will concentrate on ‘do-able things’; ones that do not require a degree in medicine to make sense of it!

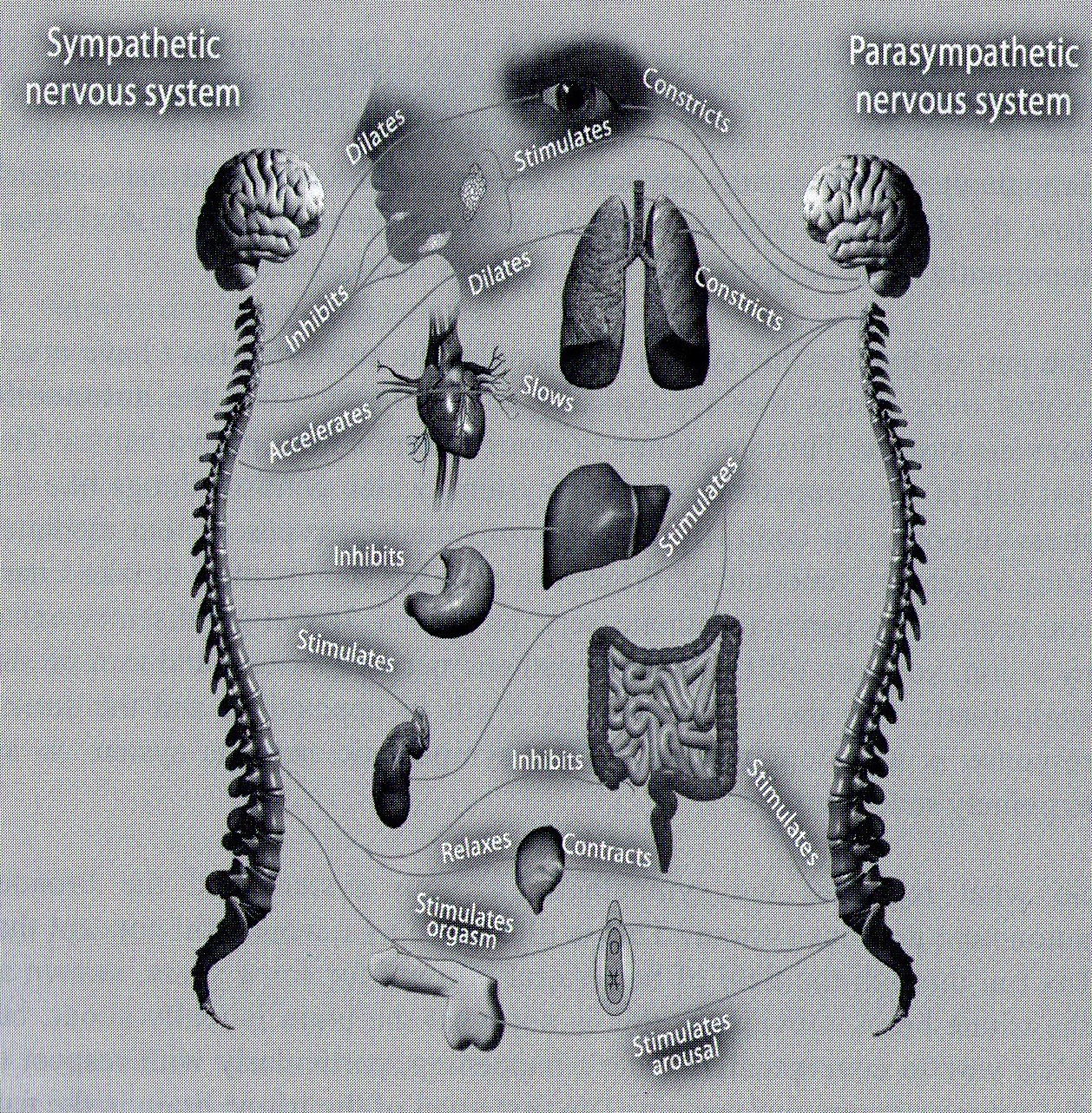

One of the more interesting systems in our bodies is the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). Again, put simply, this system comprises two parts that can either battle one with another or promote harmony and balance in our bodies. The two divisions called the ‘sympathetic’ and ‘parasympathetic’ systems. These ‘parts’ arouse or encourage some reactions in our bodies and inhibit or suppress others.

Take a look at some of the key arousers and inhibitors in the diagram below. Some very basic human behaviour are shaped by the reactions of our eyes, lungs, stomach, intestines, and sex organs.

In The Body Remembers (2000), an American therapist, Babette Rothschild, focuses on the role of memory in influencing our Autonomic Nervous system and our responses to events. Her book describes in detail how a State Dependent Memory and Learned Behaviour (SDMLB) cycle operates.

Although her primary focus is on trauma, much of what she is saying can be generalised to the treatment of anxiety (bearing in mind that PTSD, until very recently, was a generally considered to be a special case of an anxiety-related disorder).

The diagram, above, focuses attention on the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS).

Common responses of the ANS

| Sympathetic branch | Parasympathetic branch |

| Faster respiration

Quicker heart rate and pulse Increased blood pressure Pupils dilate Pale skin colour Increased sweating Cold and clammy skin Digestive processes such as peristalsis decrease | Slower, deeper respiration

Slower heart and pulse rate Decreased blood pressure Pupils constrict Flushed skin colour Dry skin Digestive process increase. |

It is the ‘ups and downs’ of these branches which will feed, and be fed by, high emotion and feelings of anxiety in particular. According to the severity of the ‘swings’, you will be tempted to flight, fight or freeze/faint. This latter response has as much to do with our Vagus nerve, as the Autonomic Nervous System.

Freeze is often overlooked, but it is a drastic survival-laden strategy that helps predators lose interest in you, or to anaesthetise you at the point of death or when experiencing serious injury. It is in such states that some people, faced with near death experiences, reported watching themselves separated from their bodies. It may be of interest to notice how these different responses emerged over millenia – starting from before human beings – indeed, mammals – were well established on our Earth.

EXPERIMENT: starting out on the scenic route

Attend to the world outside you with your eyes closed.

Without looking at the floor, desk, seat, can you identify the surface on which you are standing, sitting? Is it hard/soft; warm/cold?

What are the sounds around you?

What is the texture of the materials you are wearing? Are they smooth or scratchy; comfy or otherwise,

What is the temperature surrounding you. Is it comfy, too cold or too warm?

Without opening your eyes to look in a mirror, can you estimate the position of your shoulders, back, neck, and head? Are you comfortable on/in your feet. Do you notice any tension anywhere in your body? How do your respond to that tension?

Where, and in which direction are you looking? Are you sitting up straight? Are you relaxed or tense?

What sensations cause you to shift posture?

What experiences do you notice when you shift posture?

Do you notice and specific tastes or smells? Perhaps you notice feelings of hunger/thirst/tiredness/restlessness/stiffness or a wish to go to the loo.

Do you notice how just a little more attention helps us become more aware of internal body experiences: thoughts, feelings and sensations? Experiences that often sit there, unnoticed.

Does this kind of experiment help you to recognise just how much information is taken for granted and often left unobserved? If yes, and your notes are getting thick, then proceed on.If not, and much of the experiment seems alien to you, then return to the controlled breathing experiments and the strategies for ‘just noticing’ anything in your inner world.

This is part of a small, safe experiment I will mention a lot: the Body Scan. In this experiment, we attend to our inner world, not the environment in which we live and operate.

A FURTHER EXPERIMENT

Close you eyes and describe to yourself your current body position. Be specific about, say, where is your right arm and how is it lying, what about your left leg and back? Is the palm of your hand facing up or down/what is it next to? Are either of your feet turned out or in? In what direction is your head tilted?

Try writing down on a piece of paper your name, the day and date and where you are. How easy or difficult is that. Can you write it without thinking? Can you/do you do other things at the same time?

Now try writing the same information with your non-dominant hand. How easy and difficult is that and how much more/less ‘thinking’ goes into it?

Notice how, for most of us, most of the time, it is more difficult to multi-task than we might think.

The controlled breathing experiments already mentioned, play a large part in helping the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems to fight or co-operate. Thus, controlled breathing can counter-act the over-activity of our lungs when we begin to feel anxious. It may decelerate our heart rate and reduce rapid breathing – reactions that arise quite automatically when we feel under even a small threat.

Above all else, and crucial to our experiments, is that fact that controlled breathing is able to moderate rising emotions. Relaxation strategies help us to become more aware of what we are experiencing.

The autonomic nervous system, in full flight, will make us less aware of our experiences and less able to manage our bodies in a thoughtful way. It places us on auto-pilot and our thinking and reasoning can go out of the window. These reactions are the well-known ‘flight-fight response’.

…. but there are others. I have already mentioned a third ‘f’, freeze. There are several others, including ‘faint” and ‘flag’.

Return to:

Setting off on the the scenic route