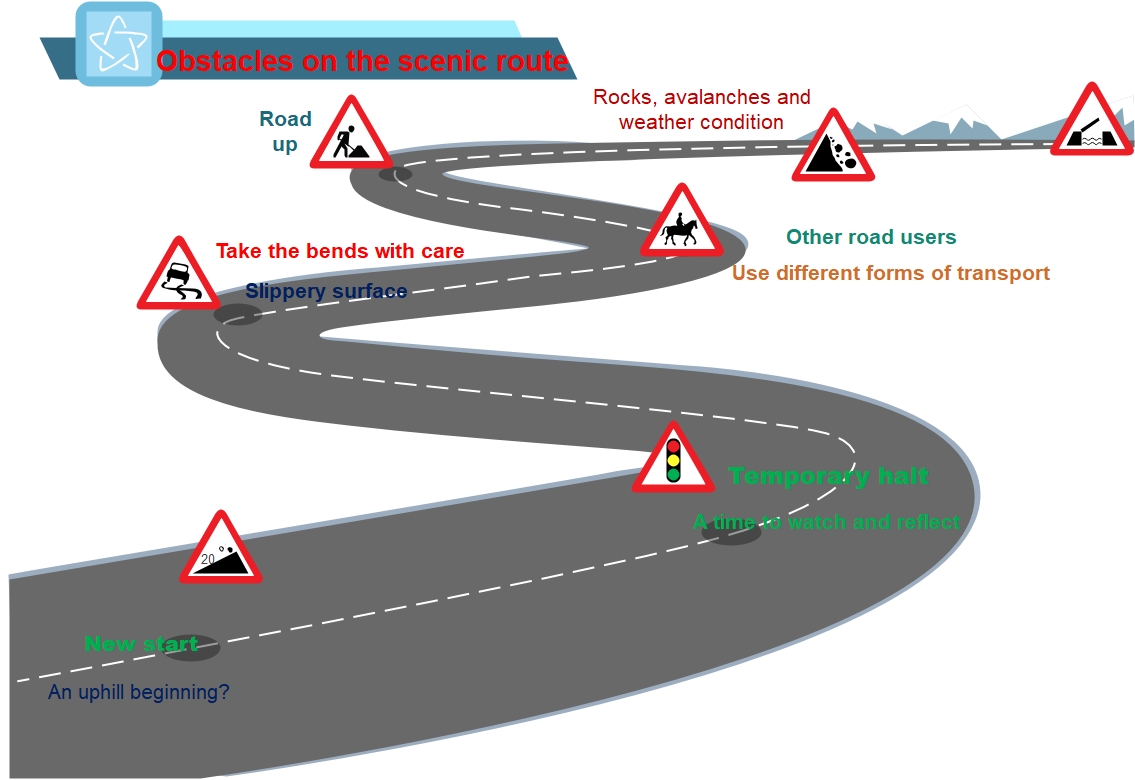

There are several obstacles to progress in therapy. As they are pretty unavoidable, I talk about ‘the scenic route’ to change.

Improvements do not happen in a straight line; there will be set backs. How we react to those ‘small defeats’ will play a key role in shaping the path of that ‘scenic route’. It can become circuitous. We can react badly to this more convoluted route, or accept that some benefits remain hidden. Consider this illustration at:

There are some clear obstacles to progress. Levels of self-confidence will make it more or less easy to keep focused on one safe experiment, and then the next one.

There are other, less obvious obstacles. Here, on this page, I will talk about STOPPERS. I identify some safe experiments to observe the things that get in the way of designing safe experiments, implementing them and learning from the results. I consider how safe experiments can help us to manage STOPPERS here, and on other pages.

As you read on, you may wish to note down information about your own personal STOPPERS.

RESPONDING TO TYPICAL STOPPERS

TIME: this feels like a genuine constraint; after all, there are only 24 hours in a day. Looked at more closely, it is possible to notice that we are impatient – we want change NOW.

Structure is a key feature from Transactional Analysis (TA).

Any of these self imposed time constraints familiar to you? What typical results emerge from these limitations? We move too fast, with too little preparation – as with New Years’ Resolutions – or procrastinate until some condition is in place, but it never is! Have you ever done something like this?

The safe experiment here is to grasp the value of small and concrete changes. All that is needed is a small change – one that can be pursued this afternoon or tomorrow. As ever, we need to notice what small things are happening, when they happens.

Smart Objectives can help us here

PACE: relates to TIME. When we push ourselves to get something done too rapidly, things can go wrong. It’s one thing to get on with a small safe experiment, and it is another to do it like Lewis Hamilton.

There are very few things that are both urgent and important so the safe experiment may need to take time; time to examine the safe experiment with consideration. It may be possible to break it down even further – into even smaller steps – based on what is important and urgent to you.

Do small, urgent and important first and set your priorities so that you get your results over time, in a systematic and ordered way. Without that care, it is possible to not notice an important ‘result’. It’s my view that there is no small, safe experiment unless I know the ‘result’!

DRIVE

Some of us are inclined to drive ourselves hard. In the Transactional Analytic model these are the DRIVERS: internal motivators that help us focus our efforts. One such Driver is Try Hard and another is Hurry Up.

Others of us are inclined to want the safe experiment to be perfectly designed to produce the perfect results (the Be Perfect Driver). These normal motivators do get results, but it is worth noticing the price we pay for them and what ‘antidotes’ there might be to respond to them differently.

CONTEXT

Sometimes we can lose the ‘woods for the trees‘. We can look at change as a dubious option – one we prefer to side-step or avoid it. Aspects of our past, and upbringing, can set off amber or red lights in our mind; these warning lights are triggered by ‘injunctions’ from our past. They whisper to us: “do you really want to do this ….. I would not do this if I were you“.

That message can get stronger the more there is a threat to a ‘rule’. That ‘rule’ is often laid down by our families – parents and grand-parents – but at an unconscious level. It’s not so much that, later on, we will hear the specific words of warning offered by those authority figures. By then, the message is so deeply entrenched in our lives that words are not needed. A mere glance will do it.

Indeed, a mere metaphorical glance in our own heads will do it!

Family messages: Scripts and Drivers

What are these family messages? Well here are those some of those messages that Transactional Analysis (TA) call Drivers. An example of a safe experiment for each one is offered:

TRY HARD: here the antidote is to practice living with ‘good enough’ – even electing not to complete a task. There is a difference between choosing not to do something – quite consciously – rather than simply put it off.

HURRY UP: as you might imagine: the antidote is an affirmation to yourself to slow down. To speak slower on purpose and to complete a task more slowly, whether it is an everyday event like cooking a meal, or a more prolonged task such as preparing to go on holiday. Smart Objectives can help here as planning things will, by its nature, slow us down. We will see that the route to success is not a straight line, but the scenic route once again! It may help further to explore the notion of the ‘critical path‘.

BE PERFECT: reciting the affirmation “it’s OK to make mistakes” can be an antidote here, affirming that your outcome is good enough. Another alternative is to look at a mess you have made in a dispassionate way! Easier said, than done!!

PERSONALITY: again, you may think your personality is a ‘given’ and little can change it. It need not be a Stopper. True, our personality is rather engrained. However, you can use the safe experiment of ‘Acting as if ….‘. Here, you act differently, quite deliberately. This is not an easy safe experiment. It will feel awkward and other people may look at you oddly. Even so, every now and again, you may notice something that you can do differently, until it becomes part of your ‘new normal’. This antidote is tricky if you experience the ‘impostor syndrome‘. The safe experiment magnifies that experience, and the aim of an antidote is to dilute things – or help you distance yourself from things.

RESOURCES: here is a major Stopper. If you do not have the resources – things, possessions or qualities – that could make a difference, then wishing for them will not make it so. However, there are other resources you can develop – especially if you have the help, support and affection of others in your life. The safe experiment here is to identify the shortfall of resources in your life. With that knowledge, take time to explore what you can do, as well as accept what you cannot do (if only at this time in your life). When you write this information down, you may find other people in your life willing to help you find creative ways of boosting your resources. One safe experiment is to complete a personal SWOT analysis, described in more detail on this page. The SWOT is a written exercise using a matrix to identify and improve your skills in self-management. See some useful examples at this web site.

VALUES: Most of our judgements about things are hidden from view but they are powerful influences on the way we act. For instance, one big problem with small, safe experiments is that they can appear trivial or irrelevant to the main objective. The result of an experiment may not be good enough to us. We might say: “That’s an obvious outcome, isn’t it? I was expecting more, or wanting more.” There may be times when it is not easy to see the point of an outcome you have obtained. In this situation, the safe experiment to THINK-JUDGE-ACT may help to re-assess your results. Note how easy it is to act without thinking.

If it helps, revisit the Acceptance and Commitment model as it can help us revisit the values that lead us to criticise ourselves and others.

NEGATIVE THOUGHTS

Negative thoughts can be a major obstacle to our success – more often because we do not notice them and/or we are reluctant to label them as such. It’s rather too easy for them to be ‘just normal’.

Negative thoughts these have several characteristics. They are:

- automatic; likely to pop into your head without any effort on your part

- distorted; do not fit all of the facts.

- unhelpful; making it difficult to change and likely to stop you from getting what you want out of life.

- plausible; encouraging us to accept them as facts and stopping us from questioning them.

- involuntary; you do not choose to have them, but you can manage them differently.

Negative thoughts can trap us in a vicious circle. The more depressed we become, the more negative thoughts we have, and the more we believe them. The more we believe them, the more depressed we feel become. It is possible to feel that life is not worthwhile. On this hyperlinked page, there are experiments to help us break out of this vicious circle. Here are some more:

EXPERIMENT

Consider this: you already beginning to break a circle of negativity by attending to these words. You may not be aware of doing so, but reading this may increase your awareness of what you are doing.

For a start, the bullet-points, above, may have led you to recognize a negative thought. You will be more aware of what happens when you dwell on such thoughts.

You may begin to feel more positive and start to seek a realistic way to test out some alternative actions. So, step one is:

1: Becoming more aware of negative thoughts even if they are not easy to catch. The first step in overcoming negative thinking is to become aware of the thought

2. What is the impact of a negative thought on you. USe Body Scanning to jut notice the feelings and sensations that seem connected to a given negative thought.

The best way to become aware of negative thoughts is to write them down as soon as they occur. Every time you notice an uncomfortable feeling, there will be a negative thought attached to it somewhere.

A final STOPPER I want to mention here is rumination – the tendency to let our 24/7 conversation, in our head, dominate our lives. In my business, this conversation is call ‘internal dialogue’ and it is common for such dialogues to disrupt our comfort. At night we can lie in bed pre-occupied with something that occurred – or is about to occur. The pictures we see in our head, and the words we hear, are ‘internal dialogue’.

Many times, I am asked how such thoughts can be stopped or silenced. This is a demanding safe experiment as it is not easy to stop things; the human body and our mind operates 24/7. Up to now I have encouraged you to start something else, rather than work to stop an experience.

Stopping is tricky; us humans seems not to take kindly to silence and inaction!

That said, some thought-stopping in relation to negative thoughts can be helpful as my negative thoughts reduce my energy and reduce my motivation. My view of the world can become skewed and my behaviour can become self-defeating.

AN EXPERIMENT with self-talk and anxiety

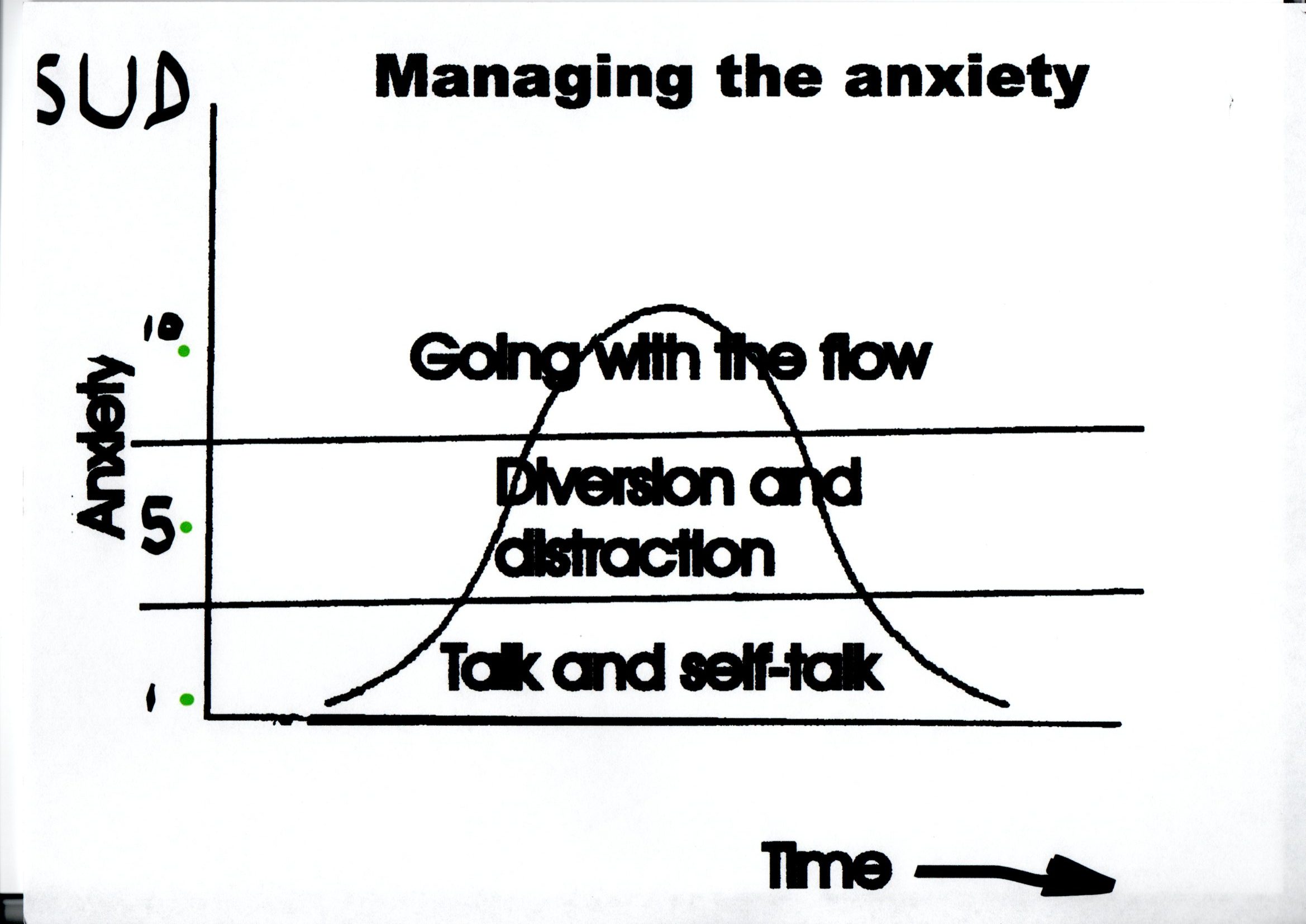

Take time to assess and just notice some of the negative self-talk that goes on in your mind. Here, I am asking you to generate a negative thought, so choose something minor – preferably, something that generates a Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD) of 1-3 only.

The diagram, below, illustrates my point. We can experiment with our emotions (anxiety, in the example I am offering). In the lower reaches, the quality of our self-talk can increase levels of anxiety with critical self-talk. If the gods smile, then anxiety can be reduced with kinder and more accepting self-talk.

This diagram demonstrates the place of self-talk in generating high emotion and I will have to address ‘diversion, distraction and going with the flow’ elsewhere, and in the future.

CONTINUING THE EXPERIMENT

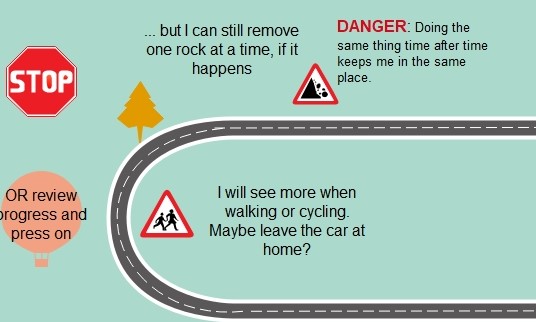

As you notice the critical self-talk and any associated discomfort, remember standing by a road side and recall your Green Cross Code. STOP, LOOK and LISTEN.

As you stop, look the negative thought in the eye and listen to something else it may be telling you. For instance, when I am cross with myself, I can be clumsy, I can stop, look and listen and notice that I am doing something too fast. Having listened, I can slow down the pace at which I am operating. HOW?

A SAFE EXPERIMENT TO SLOW DOWN

… changing your form of transport?

As you notice a negative thought, and having listened to what other things it may have to tell you, consider where you are. Look around you. Describe where you are, what you can see, what you can hear NOW. If necessary, do this out loud, but best be on your own to do that!

Become very focused on your current and immediate experience. Help sustain this ability to focus by controlled breathing so that the in-breath increases your attention on the immediate experience. The out-breath can enable you to let go of the tensions of the day – and any negative thoughts that seem to remain. Watch those tension ‘float away’ on your out-breath.

At some point, note the feelings and sensations that you were aware of. Note some small action that may help you to take to take better care of yourself.

Jennifer Sweeton has some other useful comments to make about the problems that arise when small, safe experiments do not have ‘slowing down’ at their heart. I summarize her view:

If you want to target the amygdala (our ‘fear’ centre) or the insula (that allows you to feel internal experiences) you may find both are difficult to regulate. The techniques are simple enough, but not easy.

For the amygdala, you’re going to need those relaxation techniques. You’re going to need the deep breathing techniques. You’re going to need those somatic techniques where you’re breathing as you’re moving. This is where the yoga comes in, the Tai Chi and the Qigong comes in to relax the body.

Even so, we need to get the insula on-line; to ensure ‘sync’ing‘ between the different parts of our brain.I f the insula is offline, then dissociation may be observed. There is a disconnect between parts and that can be bad news. Van der Kolk and others suggest that putting the brain back with our body is more likely if we can sense what the body is doing. Then the body can give information to us about those experiences. Somatic techniques help here – say, the Body Scan – but the body needs time to just notice those experiences and to pass on the relevant information.

Techniques that sooth the Amygdala, such as controlled breathing and progressive relaxation also support insula activation. This is one of those “bottom-up” techniques I mention.

If these work, and this does not need to be constant and forever, then more sensitive sensori-motor skills can foster more self-regulation and more clearheadedness; maybe enough to focus further small, safe experiments.

Such work on memory will involve other parts of that ‘not so smart and older sibling‘. Consolidating the hippocampus also requires time and a certain pace of working. Shifting memories, without erasing them, can make some more tolerable. BUT such exposure to memories need to take its time; the pace of work needs to be carefully negotiated.

Such shifts in direction, move safe experiments from bottom-up strategies to to top-down ones. where we’re working with our mind or our thoughts to change the brain.

Sweeton usefully concludes that ” all of those things together really are what make trauma treatment most effective“.

Further leads to consider

Taking the scenic route to change